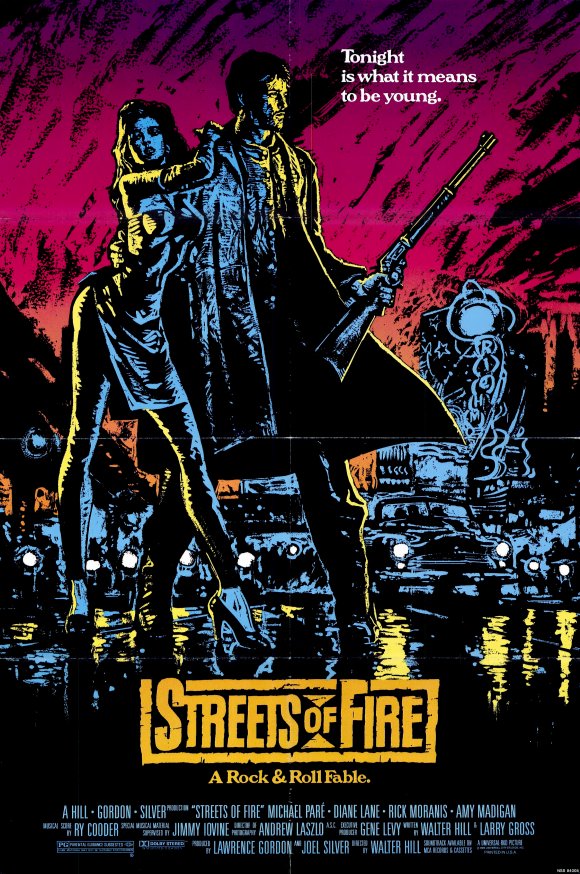

Walter Hill’s Streets of Fire (1984) opens with a disclaimer of a subtitle, “A Rock & Roll Fable,” before introducing us to its world of “another time/another place.” It’s the equivalent of letting us know that it’s a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away: a retro-future or forward-thinking past that exists in a wormhole beyond genre. Hill is conjuring this highly original landscape out of disparate elements: postwar noir, Depression-era crime story, Westerns, 50’s biker movies, rock and roll movies, 80’s MTV, even a bit of Mad Max. The look and sounds vary wildly as you drive from street to street, from backlots to location shooting under the Chicago “L.” As in his earlier masterpiece, The Warriors (1979), this is a fantasy take on urban life, with boroughs divided by colorful tribalism – not too dissimilar from Escape from New York (1981), minus the science fiction hook. The only connecting thread between these subcultures is an awe of rock & roll. That, and the collective exposure to drenching rain and searing lines of neon. Hill’s characters are intentionally broadly drawn, spouting hard-boiled dialogue and not so much belonging inside a pulp magazine as on its cover. Vehicles are casually stolen and driven really, really fast. Everyone has a gun. Bill Paxton is a bartender with a missing tooth. Everything explodes really easily, and punches connect with the crunch of battering rams. This is the kind of detailed cinematic universe in which you might want to spend more than a weekend walking around, assuming you had the right protection.

Diane Lane as rock star Ellen Aim, fronting the Attackers.

Hill was coming off the blockbuster hit of 48 Hrs. (1982), which gave him the leverage to mount this dream project for Universal. As so often happens in situations like these, such a personal, singular, lovingly crafted film didn’t find its audience until home video. In June of 1984 this poorly-marketed wildcard was up against Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, two films where eager audiences knew exactly what they were going to get. Yet the PG-rated Streets of Fire (which probably would have been PG-13 if it had been released in Temple of Doom‘s wake) is every bit the broad-appeal comic book adventure the summer season treasures. True, it’s an idiosyncratic vision, but the story is well-worn (for better or worse). The setting has the look and feel of a post-apocalypse adventure movie; everything is dirty and crumbling. The hard-bitten, seemingly amoral mercenary proves that he has a good heart when the chips are down. The villain is properly, shamelessly evil. There’s even a princess to be saved, memorable sidekicks for the journey, and engaging scenes of tough people beating the bejeezus out of each other. The fact that the songs are almost universally excellent – this is, in fact, a rock musical – shouldn’t have hurt. The film features songs written by Jim Steinman (best known for his work on Meat Loaf’s Bat Out of Hell), Stevie Nicks, and Tom Petty, among others; and performances by the Blasters (Dave Alvin’s sweaty rockabilly group), the Fixx, Dan Hartman, and Ry Cooder. Cooder also wrote the score, which is one of the best decisions Hill made: it always sounds like if a fight isn’t about to break out, a rock concert will.

Willem Dafoe as Raven Shaddock.

And although the best opening sequence of 1984 must remain the mix-up at Club Obi Wan in Temple of Doom, Streets of Fire is a close second. Hill cuts an adrenaline-pumped rapid-fire montage of screaming fans crowding into a theater to see a performance by Ellen Aim and the Attackers; her manager and boyfriend Billy Fish (Rick Moranis, almost simultaneously appearing in Ghostbusters) frets on the sidelines; Diane Lane, 2 years after playing a teenage rocker in Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains (1982), runs onto the stage and takes the microphone; a few minutes later, the leather jacketed gang the Bombers, led by the sadistic Raven Shaddock (a shockingly young Willem Dafoe), storm the theater and abduct the main act. The streets outside the theater descend into brutal chaos, the Bombers like a Viking horde. The next day, Billy hires Ellen Aim’s ex-boyfriend Tom Cody (Michael Paré, fresh off Eddie and the Cruisers) to find and rescue her, convincing him only by paying out a small fortune. Cody, an ex-soldier, agrees to pay 10% to a gun-toting drifter, McCoy (Amy Madigan, sensational), who will quickly prove her worth. The three lay siege to a biker club where the Blasters are performing and a dancer in fishnets and nothing else entertains the crowd, and soon the title of the film becomes literal as Cody sets up distraction after exploding distraction to misdirect Raven’s psychos. If it’s surprising enough to see Moranis in a prominent role in an action film (in a bowtie, no less), there’s also the left-field cameo by Ed Begley, Jr. as a helpful hobo, Paxton’s aforementioned bartender (who gets punched in the face by Madigan), and even a pre-Hollywood Shuffle Robert Townsend.

Michael Paré as Tom Cody.

The film builds to three major setpieces, the first being the rescue of Ellen Aim and the second being the final confrontation between Cody and Raven, which involves much pummeling in the middle of the street for an audience of just about every single character who has appeared in the film, including the entire police force. But the real finale is a full-circle blowout concert back at the old theater; so this is, in the end, a musical. This stretch features the film’s biggest hit song, Dan Hartman’s “I Can Dream About You,” which is still the most recognizable thanks to its ubiquity on 80’s radio; it’s also, ironically, the most dated number, sorely sticking out. Much better are the film’s two songs written by Steinman, credited to Fire Inc., to which Lane lip syncs using the combined voices of Laurie Sargent and Holly Sherwood. “Nowhere Fast” and “Tonight is What it Means to Be Young” are pleasingly histrionic, soaring power ballads that are convincingly dressed up as in-film hit songs. But everything in this film is playing self-conscious dress-up: baby-faced Lane acting not just the rock star but one that’s been around the block a few times; Moranis with his torrent of tough guy lines; Dafoe sporting, at one point, a pair of slick black overalls that look like they were purchased at a sex shop; a still-green Paré trying to bear the weight of a character who’s meant to be Humphrey Bogart, Marlon Brando, Harrison Ford, and Sylvester Stallone fused into one. Only Amy Madigan, as McCoy, and Deborah Van Valkenburgh (The Warriors), as Cody’s sister and moral center, feel completely “authentic,” for however much that matters in a film like Streets of Fire. And it doesn’t really matter for as much as you’d think, because Hill’s self-aware about all this, and expects you’re in on the joke – and don’t mind indulging in it all, when there’s so much rain, fire, neon, sweat, and rock & roll.