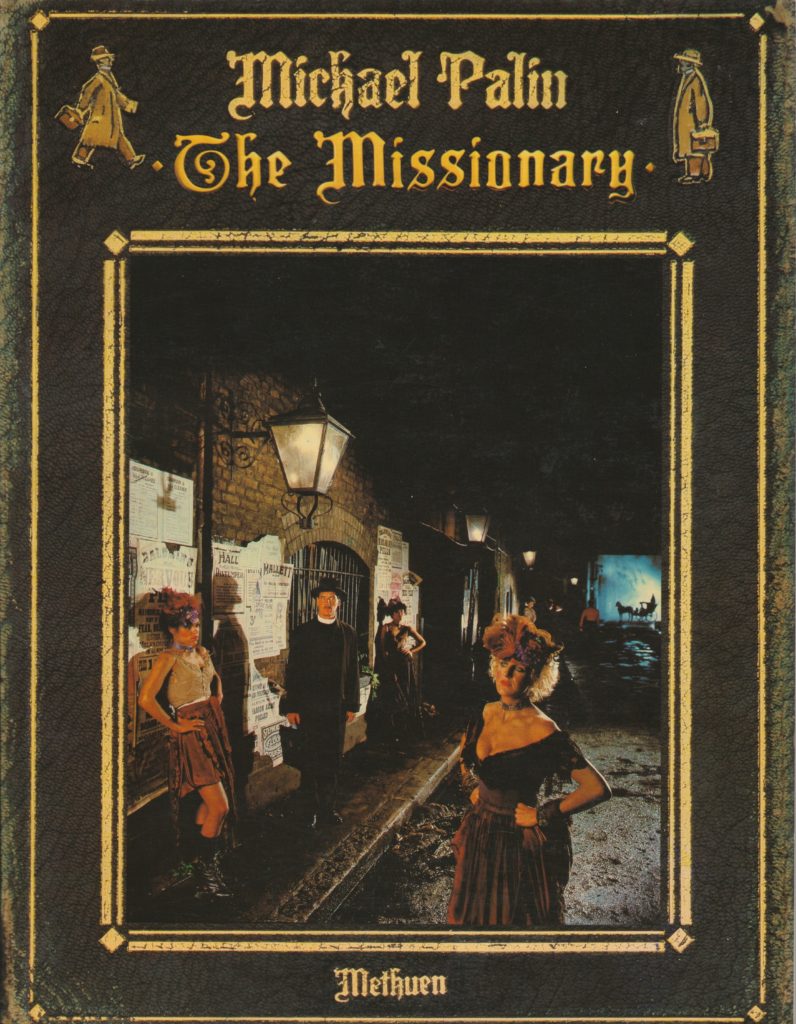

In 1982, Monty Python began filming its swan song, The Meaning of Life (1983), which would close with the opening credits of 1969’s Flying Circus playing on a TV set drifting off into space – a fitting bookend to 15 years of Python comedy. The Pythons were focusing ever more on their solo projects; getting together to collaborate had become strained. Michael Palin, sensing the dissolution and watching his friends and colleagues launch new endeavors, decided to write a comedy film, conceiving of an early 20th century clergyman, having spent a decade as a missionary in East Africa, reintegrating into sexually repressive English society and finding his newly liberal attitudes, informed by the tribesmen he befriended, at odds with everyone but the down-to-earth “fallen women” to whom he proselytizes. Casting himself in the lead, Palin saw it as being in spirit with his and Terry Jones’s 1976-79 series Ripping Yarns, each of which was a self-contained parody of tales found in the likes of Boy’s Own magazines; though it was also not far in spirit from Jabberwocky (1977), Terry Gilliam’s film in which he starred as a typically plucky Palin naif, wandering by accident through different strata of society. Like Jabberwocky, The Missionary has one foot in broadly satirical Pythonesque comedy, another in a rigorously detailed world populated by distinguished British actors rather than comedians. Palin set up the film with Denis O’Brien and George Harrison at HandMade Films, the company created to finance Life of Brian (1979) and for which Gilliam and Palin had just made Time Bandits (1981). This time, the director would be Richard Loncraine, who had directed The Haunting of Julia (1977) and Dennis Potter’s Brimstone & Treacle (1982), and would later go on to the acclaimed 1995 adaptation of Richard III with Ian McKellen. Palin would soon become the celebrated host of globe-hopping television travelogues, but for now, at least, he would be a big-screen leading man. The film was never going to be a global hit, nor was it meant to be; not only is it proudly British but it’s also uniquely Palin in its sensibility, point of view, and unassuming charms.

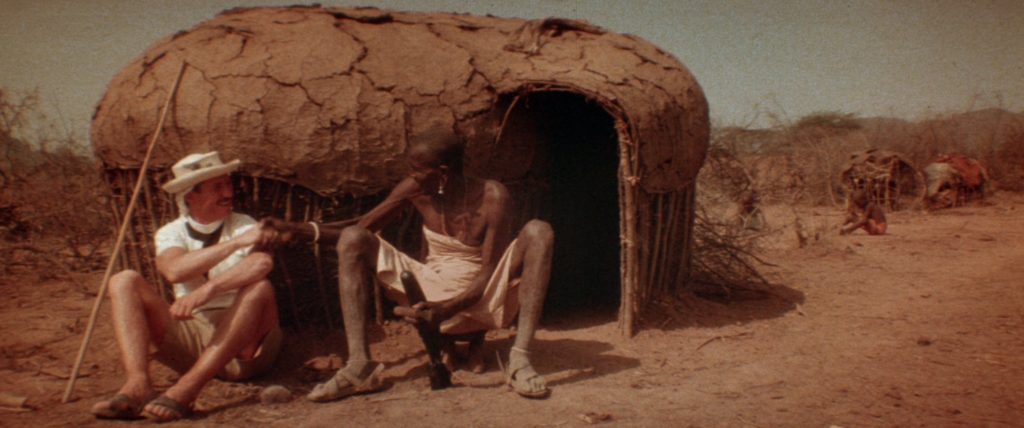

Rev. Charles Fortescue (Michael Palin) in East Africa.

The film opens with Charles Fortescue’s name being carefully obliterated with black paint on an honors board in an English public school, perfectly framing the narrative as the story of one man’s tumble into disgrace. Reverend Fortescue arrives back in England to be reunited with his fiancée Deborah Fitzbanks (Phoebe Nicholls), who is obsessively organized: “I’ve kept all your letters…they’re upstairs, in numbered boxes. The first eight boxes are general subjects. They’re subdivided into specific sections. And there are six for particular subjects: birthdays, Christmas, Easter, that sort of thing. So I can find July 8th 1898 – see ‘Elephants’ box five, section three…” She anxiously awaits their impending wedding, but skillfully retreats whenever he moves in for close contact. In London, Fortescue visits the Bishop (Denholm Elliott, who had also appeared in an episode of Ripping Yarns), expecting to be appointed as a prison chaplain or something along those lines. Instead, he’s asked to go out into the streets, speak with prostitutes, “find out why they do what they do, and stop them doing it.” Seeking to raise funds for a mission for this purpose, Fortescue appeals to the sex-starved Lady Isabel Ames (Maggie Smith, never funnier), wife to the impossibly wealthy, impossibly bigoted Lord Henry Ames (Trevor Howard). Lady Ames tells Fortescue at once that she’s attracted to him, and though he resists her advances and retreats back to Deborah, she insists he go right back and ask for the money, ignorant of what this really means he’ll have to do. Soon Fortescue has his mission, even though the price has been his own prostitution. Rumors begin to spread to the Bishop that Fortescue has been having relations with the women he’s taken in – and he has, with some of them, a byproduct of treating them with the tenderness and attention they’re seeking. As one of the prostitutes tells him, “Do it and enjoy it; it’s not the end of the world.”

Fortescue reunites with his fiancée Deborah Fitzbanks (Phoebe Nicholls).

The film boasts rapturous soft-focus photography by Peter Hannan, who had shot Loncraine’s previous films and would go on to lend an unexpectedly handsome look to The Meaning of Life. With such painterly compositions the film looks like a Merchant Ivory production, which is appropriate given that’s the genre it’s parodying. The look also enhances the gags. In one long take, Fortescue, visiting a lord and lady who are potential benefactors, launches into an impassioned monologue while pacing in the background of an ornate parlor; in the foreground, the lady gradually realizes that her husband has just passed away in his chair. At the end of the scene, a maid covers the body in a white cloth, so that he disappears into the scenery amidst the rest of the draped furniture. A remarkable extended bit sees a butler (Michael Hordern) with a very poor sense of direction leading Fortescue back and forth through Lady Ames’s vast mansion, wandering into closets, through the cellar, and finally outside, where the entire building fills the four corners of the screen. “I think if you won’t mind sir, we’d better walk round to the front door and start again.” He promptly walks in the wrong direction. The period detail from one scene to the next is spot on, which enhances the laughs – to see Maggie Smith, a familiar face in productions such as these (right up through Downton Abbey), understatedly but persistently making aggressive sexual advances on Palin makes the whole film worthwhile by itself. The film also features small roles for Timothy Spall, Neil Innes (who sings the song over the end credits), and a brief appearance by Charles McKeown, who would soon appear in Gilliam’s Brazil (1985) and The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988).

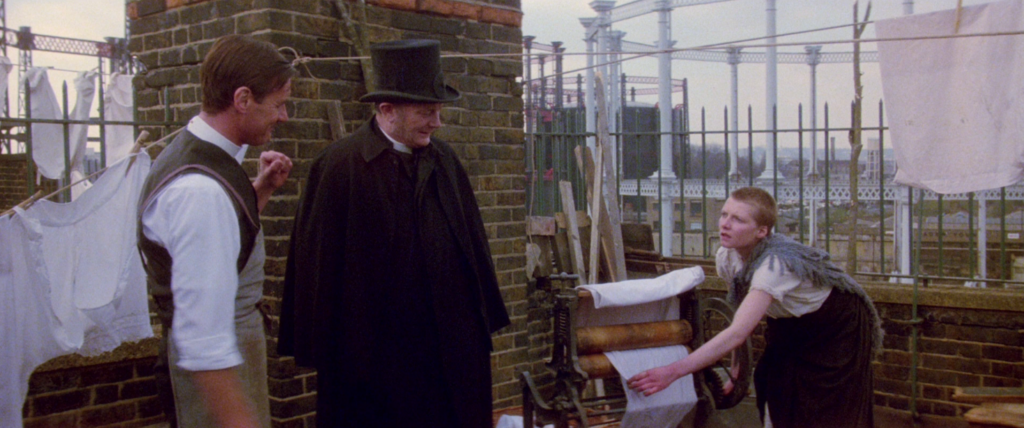

The Bishop (Denholm Elliott) pays a visit to Fortescue’s unusual mission.

The story eventually traces Fortescue’s fall from grace as he reaches self-actualization and sexual liberation outside the boundaries of society and church. This involves getting closer to Lady Ames and discovering that she’s wasn’t born into wealth – she wears her role like a mask – and that she’s about to take desperate measures against her monstrous husband. Here the film drifts amiably off the rails. Palin’s satirical targets are clear: sexual repression, hypocrisy, prejudice against the disenfranchised. The whole story seems to be building toward the establishment of the mission, and we’re waiting to see Fortescue amidst the prostitutes, the complications that ensue – and then Palin’s script all but skips over it, giving us instead an assassination subplot in which we’re not at all invested. There are three scenes set in the mission: a comical seduction with echoes of Sir Galahad in Castle Anthrax; a visit from Lady Ames in which she discovers the compromised Fortescue; and a visit by the Bishop in which he discusses the rumors about this place. It’s easy to see how another draft would have fixed the problem – excising the assassination storyline and spending the rest of the film inside the walls of the mission, and contriving to bring Deborah there, one way or another. You expect Fortescue’s two worlds to collide, and they don’t quite. The script could also stand to give more dimensionality to the sex workers, most of whom are relegated to the roles of extras. In Indicator’s excellent Region B Blu-ray release, Palin, in a new interview, acknowledges the film’s shortcomings – that the third act never lives up to the heights of the first two. He says it could use more emotion, which is astute: perhaps there was some reluctance to move too far from the broad comedy parameters established by Python and Ripping Yarns. Yet Palin was always gifted at writing warm, empathetic characters, and that shines through in The Missionary. Even though the story never quite comes together in the end, it’s a pleasure to spend time in this world.