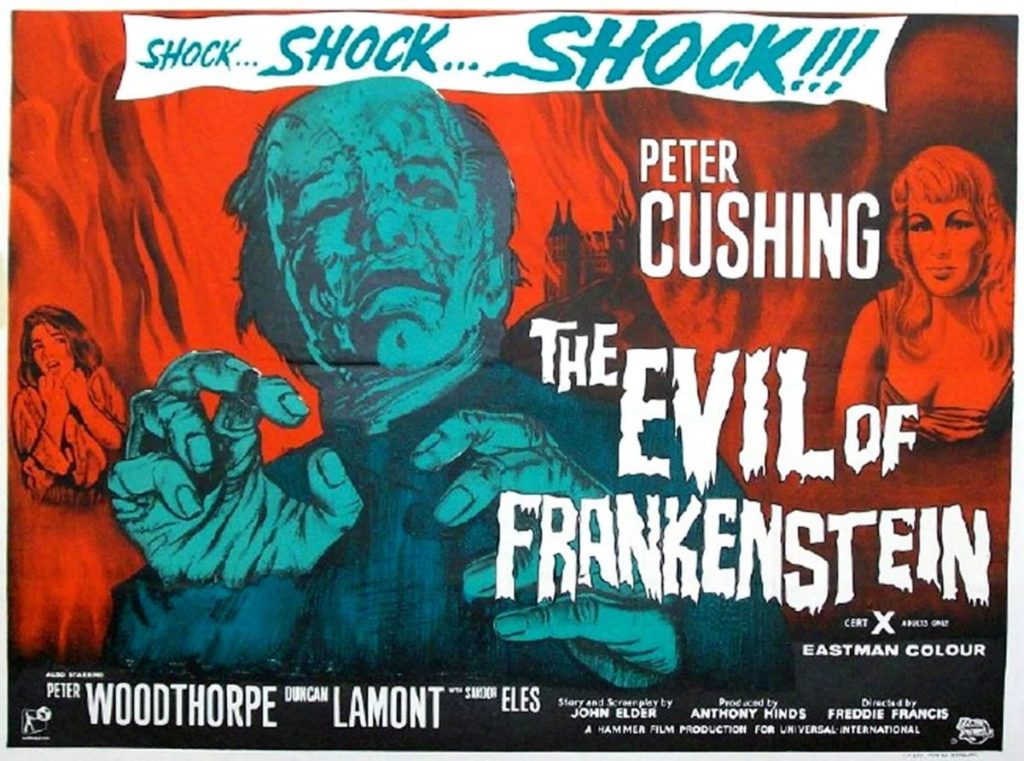

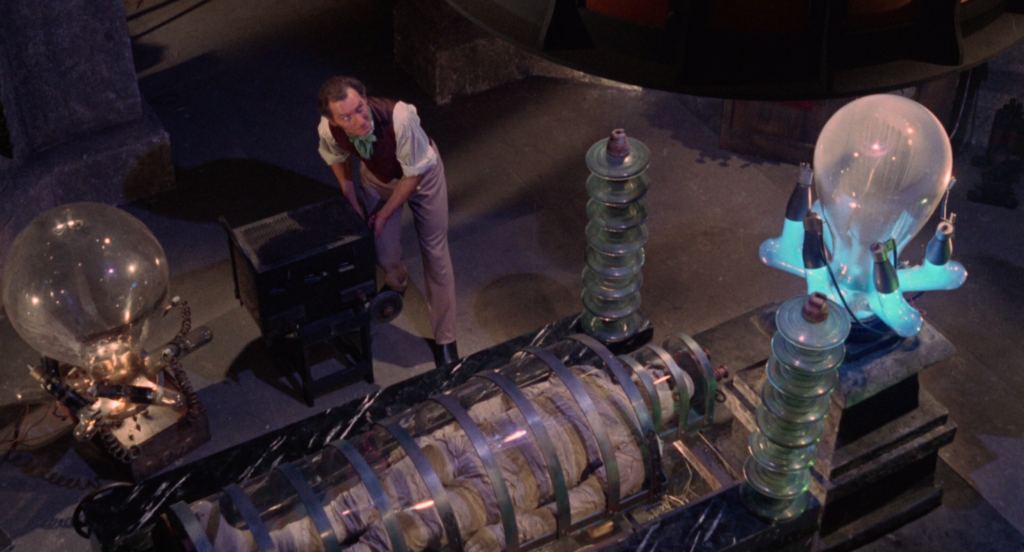

After an extended hiatus, Hammer’s Frankenstein series resumed with The Evil of Frankenstein (1964), the third installment following The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) – which kicked off Hammer horror proper – and The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958). Peter Cushing was back as the Baron, a role he would maintain for the rest of the series, excepting a certain failed reboot we don’t need to discuss here. Not returning was director Terence Fisher, whose graceful guiding hand gave the series such distinction before and after Evil. Freddie Francis, who won an Oscar for his cinematography on 1960’s Sons and Lovers, took his place, having joined the Hammer family by photographing Never Take Sweets from a Stranger (1960) and recently directing the Jimmy Sangster-scripted thriller Paranoiac (1963). As you might expect, Francis guarantees that the film looks great, though he pulls the series backward with a desire to make a film in the mold of the Universal Frankenstein films. In fact Evil was part of Hammer’s distribution deal with Universal, and they gave permission to use the makeup evoking the famous Jack Pierce monster design, from which Hammer so famously diverged with the grisly makeup worn by Christopher Lee in their first film. Francis plunges forward with a new monster evoking Karloff’s – in the broadest possible brush strokes – and a sparks-spraying laboratory set, including a lightning rod that extends from the roof, to allow Cushing to become, at least briefly, Colin Clive. In theory, this fan fiction mash-up between Hammer and Universal horror should at least be interesting. So why does it thump dead at our feet like one of the monster’s victims?

Discovery of the creature in a familiar frozen fashion.

The simple answer echoed down the decades, that the monster makeup’s to blame, is only reinforced in the thorough new Blu-ray special edition from Shout Factory. (The film was previously available on Blu-ray in Universal’s 2016 Hammer Horror 8-Film Collection box set, a mixed bag of acceptable and unacceptable aspect ratios, which Shout’s re-releases have been individually correcting as needed. Evil fell on the “acceptable” side of the fence, but lacked any special features.) The makeup on the monster is an embarrassment, especially from the standpoint that the production value on the film is otherwise superb, as is to be expected from a Hammer film in 1964. As worn by the New Zealand wrestler Kiwi Kingston – who had never acted outside the ring – it looks like a papier-mâché mask, turning the creature’s forehead into a rather sharp-angled box (to where the famous bolts have been relocated). We can see easily enough that there’s an actor peering out from inside – not that it gives Kingston the ability to express himself through it. As Hammer historians have reported, makeup supervisor Roy Ashton whipped up a flurry of ideas for the studio but was given no direction or approval until the final design was mustered at the last minute; his talent is more easily evidenced in other films, such as The Curse of the Werewolf (another recent Shout Factory release, also recommended). Even more so than many of the other Hammer Frankenstein films, this is a monster movie. By putting a retro-horror spin on the franchise and bringing in Universal trademarks, Francis only emphasizes the focus on the monster and its importance. Because the design is an outright disaster (I noted exactly one shot where I thought it looked rather menacing, but that was fleeting), the film’s center of gravity sags toward a sinkhole.

Zoltan (Peter Woodthorpe), Hans (Sandor Elès), and the Baron (Peter Cushing) inspect the creature (Kiwi Kingston).

Now that we’ve gotten that out of the way, onto the positives, which often get overlooked with this film. Cushing is in top form, especially enjoyable in the opening acts; after being driven out of a town where his equipment has been destroyed by an angered priest, he and his faithful assistant Hans (Sandor Elés, later to appear in And Soon the Darkness) boldly travel to the village where he got his start, the Baron arrogantly confident that he won’t be recognized. He dons a masquerade mask for the village festival that’s in full swing, but his pride gets the better of him when he discovers that the local Burgomaster (David Hutcheson) has raided his home and stolen all his belongings. “Even my bed!” Baron Frankenstein roars as he storms through the Burgomaster’s house, completely ignoring the negligee-clad young woman (Caron Gardner) lying upon it. She is clearly attracted to the Baron, and gets a humorously obvious sexual thrill as he locks himself in the room with her when the police arrive, then uses the sheets to form a rope to escape out the window. The Baron also meets a local carnival hypnotist named Zoltan, played with depraved zeal by an excellent Peter Woodthorpe (Gollum from Ralph Bakshi’s Lord of the Rings); Zoltan, using his powers of mind control, is the only one who can command the monster, which allows him to blackmail the Baron. Also excellent are Duncan Lamont as the Chief of Police, and Katy Wild as a deaf-mute beggar who falls in with the Baron and Hans. Unfortunately, a subplot in which she forms a sympathetic bond with the Baron’s creation never has a chance to land an emotional impact, thanks to the inadequate creature currently in use.

Zoltan manipulates the creature. In shadows, the limited makeup is more effective.

The plot lumbers on like the monster – not helped when it’s delayed by an extended flashback sequence showing the Baron’s creation of the creature years before. (This is essentially a soft reboot of the series, ignoring the body-switching ending of The Revenge of Frankenstein as it harkens back to a more Universal-centric origin story for the Baron. If one does some mental gymnastics and squints just right, you might be able to keep it all in the same continuity.) Katy Wild’s beggar girl helps the Baron and Hans rediscover the creature who’s been frozen in ice inside a cavern, a la Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943). As Zoltan insinuates his way into their lives, at one point he considers raping Wild’s character, an unfortunate notion which is thankfully discarded quickly. The creature finally goes on a rampage, and the film ends with a climactic fire – a rule, it seems, for most of the Cushing series – before a tower in the Baron’s castle explodes. You’ll be pressed to remember anything else happening in this film even minutes after it’s ended; it’s as though following the Universal tropes, already growing creaky by the 40’s, has flattened the material far too much. It certainly doesn’t give Cushing a lot to do – the shining star of the series, far more than its various monsters. We enjoy seeing the Baron scheme and double cross and murder from one village to the next, but at this stop he mostly stews. The Shout release’s supplements include the alternate cut made for US television which is padded with footage shot without the main cast. It also includes the 1958 Anton Diffring-starring pilot for the series Hammer produced for American television, Tales of Frankenstein – this also paying homage to the old Universal movies. (Evil of Frankenstein producer and screenwriter Anthony Hinds took plot elements from one of the unused Tales of Frankenstein scripts, namely the idea of a hypnotist controlling the monster.) Other extras include interviews and an excellent commentary track by historian and author Constantine Nasr.