Richard Matheson’s 1954 novel I Am Legend is one of the 20th century’s most influential pieces of genre fiction, the saga of a weary, grief-ravaged man who believes that he’s the last of his kind on Earth, all others having succumbed to a virus that leaves them in a state like vampirism – recoiling from their reflection or garlic; slain only by stakes; coming out in droves at night. The protagonist, Neville, survives by becoming an exterminator, chasing down the vampires during the daylight hours and driving stakes through their hearts, while gathering supplies for his barricaded home, around which the infected gather night after night. Despite the novel’s focus on a scientific explanation for vampires, the book – and its first adaptation, The Last Man on Earth (1964) – sowed the seeds for the modern vampire film: George A. Romero has cited both as an inspiration for Night of the Living Dead (1968), and the shadows of I Am Legend are cast over every “zombie apocalypse” tale that’s followed. And though it can claim many films as its progeny, the book has so far been adapted directly three times, with the 1964 Vincent Price film eventually eclipsed by The Omega Man (1971), starring Charlton Heston, and the long-in-development I Am Legend (2007), ultimately made with Will Smith in the lead role. Certainly, of the three, The Last Man on Earth is the most modest, lacking the production values of the Heston vehicle or the special effects and action sequences of the Smith film. Matheson was disappointed with the result himself, even though it was at least partially his screenplay; he replaced his name with a pseudonym. This is, however, as close an adaptation of Matheson’s original novel as has yet been made, and its modest, simplified approach to the material now stands out as a virtue.

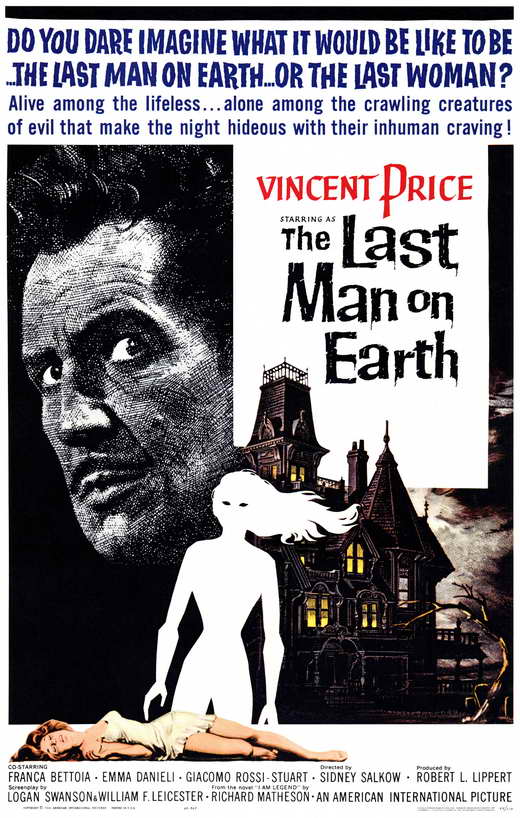

Vincent Price as “The Last Man on Earth.”

Matheson originally wrote the script for Hammer, but after a time it was determined the film would never make it past the censors at the BBFC. Hammer’s Anthony Hinds sold the screenplay off to the prolific exploitation producer/director Robert Lippert, who had distributed Hammer films in the States. The film became an Italian co-production, shot in Rome, starring Price, and directed by Sidney Salkow, who had just worked with Price on the imitation-Corman horror anthology Twice-Told Tales (1963 – adapting Nathaniel Hawthorne instead of Edgar Allan Poe). Matheson liked Price – he had, after all, written several of those classic Corman/Poe pictures – but not for this part, and he was unenthusiastic about the choice of the journeyman director Salkow. You can play your own parlor game of who would have made the better Neville circa 1964 (for me, it’s John Cassavetes), or who would have been a better choice of director. But we have what we have, and for fans of Price, this is essential viewing. There’s no winking to the audience, no suggestions of comedy. Price’s character, renamed Robert Morgan here, is emotionally coming from the same place as Matheson’s creation. He’s a man so hardened by his grim routine and the tragedies in his past that he’s been stripped of hope, his humanity worn down like the stakes he endlessly carves in his fortress-like home. Price gives one of his best performances, meeting the material at just the right level.

Arriving home late means a battle for survival.

The story follows the novel closely, with one key change: Morgan/Neville is now a scientist who was researching the virus when the pandemic struck, rather than a man forced beyond his expertise (over the course of years) to research the vampires. This change adds an element of coincidence to the story: his survival doesn’t seem to have anything to do with the fact that he was studying the outbreak, and he speculates a bit absurdly, as he does in the book, that he may have immunity because he once bitten by a vampire bat. Still, the change is a logical one to expedite the storytelling and explain how he can become such an expert on the creatures that bang on his door every night. The first act is the film’s strongest, with Price wandering a deserted city, corpses strewn across the streets, and Salkow lending a documentary style to these black-and-white, dialogue-free scenes. (In one of the first shots of the cityscape, we can see traffic snaking down the side of the frame – a rather careless mistake.) He dons a gas mask, loads up his station wagon with slain vampires, drives them to “the Pit” where bodies were disposed en masse by the military, dumps gasoline on them and sets them ablaze. The sign in front of a vacant church says “The End Has Come.” When he visits a grocery store to stock up on garlic, there’s a fantastic little moment where Price kicks away the cans littering the floor without a glance down at them. The gesture contains a bitter impatience which tells us so much: he’s been here dozens of times, he hates the routine into which he’s been forced, he’s sick of the mess yet it’s pointless to clean anything up. But he’s also, as he says in narration, a “heartbeat away from Hell.” The first scene where the neighborhood vampires come staggering zombie-like into his driveway makes the Romero influence distinct, even if Salkow is less skilled at building the sense of threat. The vampires have languid movements, but when Morgan corners them in their suburban lairs in daylight, Salkow creates an effectively queasy treatment of the vampires weakly trying to fend Morgan off as he holds them down and lifts his stake.

Morgan meets Ruth (Franca Bettoia).

Those moments gain resonance in a late-film twist, as we learn of a new race being born from the plague, embodied in a woman, Ruth (Franca Bettoia), whom Morgan is surprised to encounter on one of his walks. He comes to learn, as he does in the novel, that he is as much a “legend” to them as vampires were to him – an impossible being who has been attacking their kind, and must be rounded up and executed. That they descend in military vehicles and are indistinguishable from the army we see in the film’s flashbacks is potentially rich thematic material that’s unconvincingly delivered and weakly explored; Matheson does a better job in the novel of explaining their backstory and wringing some irony from the situation (in addition, enough time passes in Matheson’s book to make their existence more plausible). The film has another weakness in its inability to hide its Italian production origins – even a newspaper headline in English bears a conspicuous grammatical error – but personally I find the European touches, even a bit of quasi-neorealism, add to the film’s charm. Of course, watching this film during a real global pandemic deepens the film in unexpected ways, such as in a flashback of the birthday party for Morgan’s daughter, in which his wife cuts off a discussion of the spreading virus by offering the empty reassurance: “With the whole world trying, there must be a solution. Right now our problem is to cut that cake.” But there is no solution to be found, and the film’s most horrifying moment comes when Morgan refuses to follow the order to let the dead be gathered for burning: instead, he buries his wife, and she comes back that night knocking on his door. Her reveal could not be bettered in any adaptation of this material – Price opens the door so slowly we start to suspect the front porch will be empty – but there she is, looking very dead and walking purposefully out of the shadow, and Price’s façade of bravery vanishes. It’s a gothic horror moment that might have appeared in a different Price movie, but so somberly played that it gets under my skin more than a horde of the undead pounding on the walls.