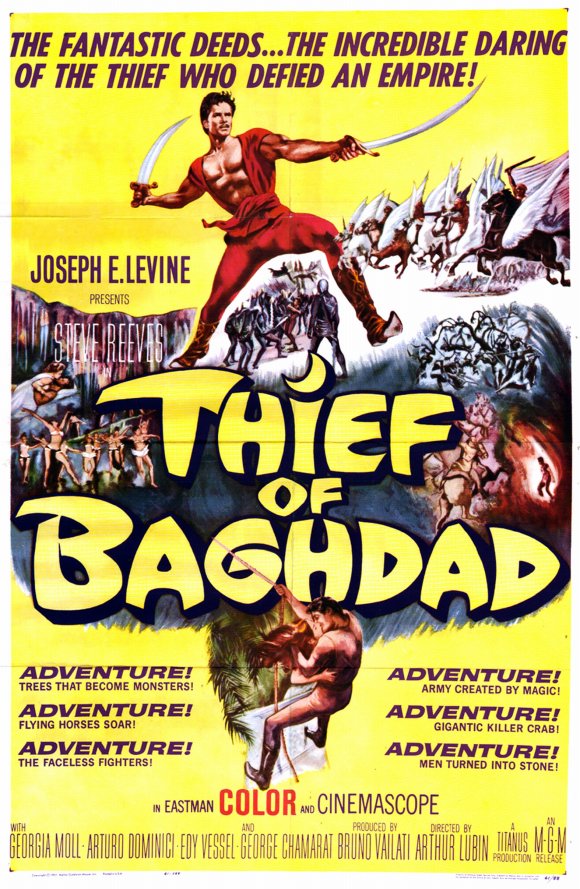

Although the Douglas Fairbanks vehicle The Thief of Bagdad (1924) was a pastiche not based on any particular tale in the Arabian Nights, it inspired a strain of remakes, each of which banked on the audience’s familiarity with the title alone. The most famous and successful of these was 1940’s Alexander Korda production starring Sabu and Conrad Veidt, the film that inspired Ray Harryhausen to take on Sinbad over a decade later. But there was also a 1952 West German film (Die Dieben von Bagdad), a 1960 Indian film (Baghdad Thirudan), and the 1978 The Thief of Baghdad starring Roddy McDowall. That Steve Reeves should have taken on the role at the height of his Italian peplum stardom should come as no surprise. Arriving three years after his smash hit Hercules (1958), this Thief of Baghdad (1961) inserted the man with the action-figure body into a standard-issue Orientalist fantasy. With Reeves’ sword-and-sandal adventures doing strong business in the States, this became an American-Italian co-production, with producer Joseph E. Levine – who had distributed Hercules in the U.S. – collaborating with Italian production company Titanus. An American director was hired, Arthur Lubin (1943’s The Phantom of the Opera), who had played with these toys before in the Maria Montez/Jon Hall vehicle Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves (1944). Reeves sports a moustache that grants a fair resemblance to Fairbanks, though he makes a more unlikely thief. A thief should be able to move unnoticed through a crowd, after all.

Karim (Steve Reeves) falls for the Princess Amina (Giorgia Moll).

Reeves is Karim, a clever thief who gains popularity with the people of Baghdad by stealing from the rich and distributing it generously among the poor. When a neighboring prince, Osman (Arturo Dominici, Hercules), arrives to court the beautiful Princess Amina (Giorgia Moll, Contempt), Karim boldly ties him up in a closet and impersonates him before the dim-witted Sultan (Antonio Battistella, The Warrior Empress), simultaneously robbing the wealthy members of the court blind. He pays a visit to the Princess and gifts her with “the Ring of the Prophet,” which is her father’s own; his disguise naturally doesn’t take him much further, but she’s smitten with him anyway. He’s arrested and placed into forced labor working at a mill, which is a series of giant wheels turned in the hot sun by slaves – an image which surely inspired John Milius’s “Wheel of Pain” sequence in 1982’s Conan the Barbarian (even the accompanying “grinding” music is reminiscent of Basil Poledouris’s score). But Karim doesn’t last long. He uses his cunning to trick his way out of the gates, and is soon competing among dozens of suitors to retrieve a magical blue rose to save the princess from a poisoning caused by Prince Osman’s “love potion.” To fulfill the prophecy, they must all dress in blue and pass through the legendary Seven Doors before finding the rose. Osman is among them only briefly; when he returns with a rose made blue by the spell of his magician, it’s exposed immediately, and he decides to take Baghdad – and the princess – by military might. Meanwhile, Karim walks through a fantasia of landscapes and challenges on his path to the blue rose.

The suitors battle living trees at the second of the Seven Doors.

This second half of the film is when it becomes intriguing as a fantasy, for each Door – and the surreal realm it divulges – passes in a fast-moving delirium. After battling Oz-like living trees, their branches thrashing like tentacles, Karim walks into a plain of fiery mud pits, plummets through a hole and stands in an underground inferno that might as well be Hell. He smashes a mirror to escape, miraculously emerging in a green glade surrounded by waterfalls. Women like Time Machine Eloi guide him to their Circe-like mistress (Edy Vessel, 8 ½), who charms him with women dancing erotically (a peplum requirement) and a spiked drink that threatens to turn him into a statue. He walks along seaside cliffs and wrestles a man who at first drapes himself in a cloak of invisibility (wrestling – a Steve Reeves movie requirement). And in scaling the mountain, the surreal images reach a crescendo as he discovers a winged horse guarded by a squadron of black leather-clad men in white featureless masks. The horse, at least, is a genuine callback to the 1924 film, whose poster featured Fairbanks astride an Arabian Pegasus (one of the stories in the original Nights includes a flying horse). Escaping on its back, Karim ascends to a crystal palace in the clouds where he discovers the blue rose. From Hell to Heaven, all in the space of about thirty minutes. For long distance shots of Karim on the horse, the film appealingly switches to cel animation. By this point, my head was sufficiently swimming that I half-expected the entire film to become animated. But this is still a matinee movie, and a climactic desert battle, however whimsical, wraps up the plot.

Prince Osman (Arturo Dominici) attempts to deceive the Princess.

The film benefits from location shooting in Tunisia (apart from the sets struck in Rome), but there’s no doubt that the story doesn’t achieve lift-off until halfway through its running time. It seems random that throughout the story Karim receives assistance by a genie-like presence, later insufficiently explained to be the ghost of a former, benevolent Sultan. The acting Sultan is a little too stupid to be believed (he doesn’t even recognize Karim when he changes his clothes and shows up in his court a day later). Giorgia Moll is given little more to do than lie exhausted on a couch. And the climactic battle is undermined by the fact that the blue uniforms of Karim and his men look an awful lot like hospital scrubs. Still, Reeves brings enough charm to push him past some limited acting, and the extended Seven Doors sequence at times suggests the peplum work of Mario Bava (who had a different Arabian Nights fantasy, The Wonders of Aladdin, on release the same year). If this Thief of Baghdad can’t possibly rival Fairbanks or Sabu, at least it captures the state of early 60’s Italian fantasy filmmaking, when musclemen in torn shirts wrestled monsters and crept into harems, with the occasional glimmer of filmmaking invention to tantalizingly suggest the truly fantastic.