The Swimmer (1968), based on a short story by John Cheever, is structured on a lean concept. Ned Merrill, indelibly portrayed by Burt Lancaster, observes that there are enough swimming pools in his suburban Connecticut neighborhood that he can swim all the way back to his house, where he can be reunited with his wife and daughters. “Pool by pool they form a river,” he says in awe. When we first meet him, he emerges out of the forest like Adam in Eden (he’s clad only in blue swimming trunks to match his pool-blue eyes). He simply materializes, striding confidently into the backyard of some friends and diving uninvited into their pool. They’re delighted to see him. They haven’t seen him in ages. If they would only be a trifle more observant, they might notice that something seems off-kilter with their old acquaintance. Admittedly, with Ned it’s easy to just not bother. With his shining-teeth grin, deflective charm, and tendency toward self-conscious poeticisms and too-romantic gestures, it’s simple enough to enjoy his novelty until he wanders off again. You wouldn’t mind his presence at a party, but find yourself alone with him and you might walk straight off the diving board into an empty pool, metaphorically speaking. Does he really mean all those things he says? “I’m a very special human being, noble and splendid,” he tells a woman he’s just met (a bit part by Joan Rivers). She looks dazzled and bemused while he suddenly tries to seduce her. A bit of her, against all reason, wants to believe he is what he says.

Ned (Burt Lancaster) takes his former babysitter Julie (Janet Landgard) on a delirious run.

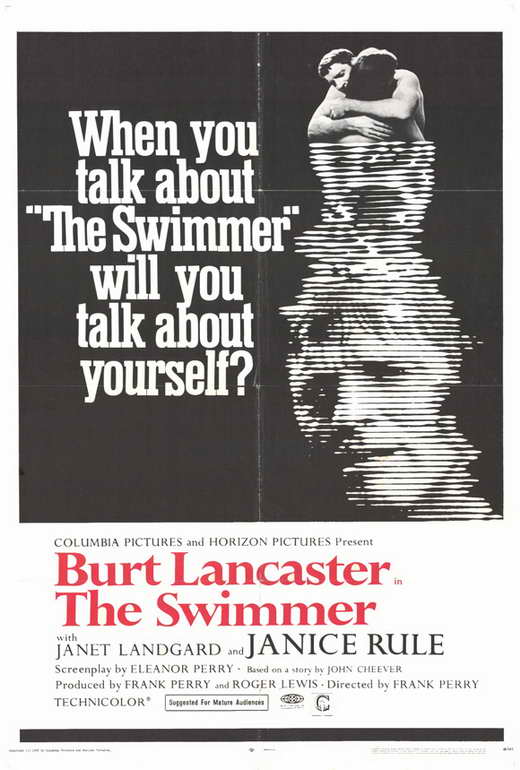

Grindhouse Releasing has reissued the bona fide cult classic The Swimmer in a special Blu-ray edition of a 4K restoration, including a feature-length documentary, and bundled with the intentionally queasy score by Marvin Hamlisch on CD. The picture is as gorgeous and colorful as a summer’s day – that seasonal confusion (leaves are falling, the sky is darkening – it’s actually early autumn) perfectly captured by DP David L. Quaid. Quaid also shot 1968’s masterful Pretty Poison, which demands to be screened as a double feature of delusion with this movie. The Swimmer was directed by Frank Perry (David and Lisa) and written by his then-wife Eleanor Perry (The Man Who Loved Cat Dancing), the pair focusing a razor-sharp gaze on the troubled character at the heart of this unusual premise. It was an easy shoot with a difficult post-production: Frank Perry was fired by producer Sam Spiegel so that Sidney Pollack could be brought in for reshoots, notably creating the pivotal scene with Janice Rule late in the film. Yet a suggestion that the film should be rewritten to provide a happy ending was thankfully ignored. As diverting as the film’s first three-quarters – satirically funny, bizarre, entrancing – it is the ending which sticks in the memory of viewers. It works so well not because it is a twist, but because the viewer has been prepared for it from almost the very first scene. The Swimmer is a mystery about a man. We don’t know very much about Ned, but we get hints, and the hints pile up in warning.

At the public pool.

For this Connecticut community, the swimming pool is a status symbol but also a reflection. A couple describe their elite filtration system with delicious fetishism. One pool sits at the foot of a glass and steel dome-shaped shelter erected proudly by their owners, who are throwing a decadent party; they boast of the expense while one of the guests drunkenly scales it and tumbles down into the water. Two elderly nudists require that he, too, strip nude to use their pool. Another pool sits empty; the child who joins Ned to sit at the edge of the concrete pit says that his parents drained it because he couldn’t learn how to swim. It’s a moment when Ned’s imagination offers the boy a catharsis – he teaches him how to swim in a pool without water, and the boy regains his confidence and joy. But just as quickly, the child walks to the edge of the diving board and jumps up and down in enthusiasm; a panicked Ned pins him down before he can hurt himself. The most uncomfortable extended sequence, when Ned becomes infatuated with the 20-year-old (Janet Landgard) who used to babysit his daughters, bravely exposes Ned Merrill’s flaws. By the time we meet Rule’s character, a woman with whom Ned once had an affair, he is nearly flayed before our eyes. And this treatment continues, remorselessly, to the tale’s conclusion. Merrill twists an ankle early on, and goes limping through his quest. Later he can’t stop shivering. He’s forced to cross a busy freeway to keep on course. His bare feet become filthy and bloodied, which leads to humiliation when he arrives at a public pool, crowded at the end of the swimming season. Through all this, Lancaster is remarkable. He never shied from painstakingly complete character portraits, and in The Swimmer he allows himself to be made utterly vulnerable, even literally exposed (those nudists and their rules…). The film lives and dies on Lancaster’s performance. Thankfully, he’s so strong that it’s impossible to imagine the film without him.