The best thing about Waxwork (1988) was its enthusiasm. The debut film of Anthony Hickox, the son of legendary editor Anne V. Coates (Lawrence of Arabia) and director Douglas Hickox (Theater of Blood), it wore its love of monster movies on its sleeve, using the tried-and-true waxworks trope to introduce what were essentially short films about Hammer-style werewolves, decadent vampires, and a rampaging mummy. The collage-like plot, which comes crashing together in an anything-goes finale chock full of rubber monsters and spraying blood, was matched by its spin-the-wheel casting including Zach Galligan (Gremlins), David Warner (Time Bandits, TRON), Deborah Foreman (Valley Girl), Michelle Johnson (Blame It on Rio), Patrick Macnee (TV’s The Avengers), John Rhys-Davies (Raiders of the Lost Ark), and Miles O’Keeffe (Tarzan the Ape Man). Part of the fun watching the film now is the obvious fact that the film’s ambition far outstripped its budget; the writing and direction are occasionally slapdash, but the practical effects are inventive and a few set pieces are genuinely striking, like a bloody vampire showdown in a white-walled chamber, or the erotic-comic revelation that the “good” girl Sarah (Foreman) is less interested in Galligan’s vanilla-romance overtures than the whip of the Marquis De Sade (J. Kenneth Campbell). In the end credits Hickox dedicated the film to his heroes: Joe Dante, John Landis, John Carpenter, Dario Argento, George Romero, and Steven Spielberg – somewhat redundantly, given how overt those references are.

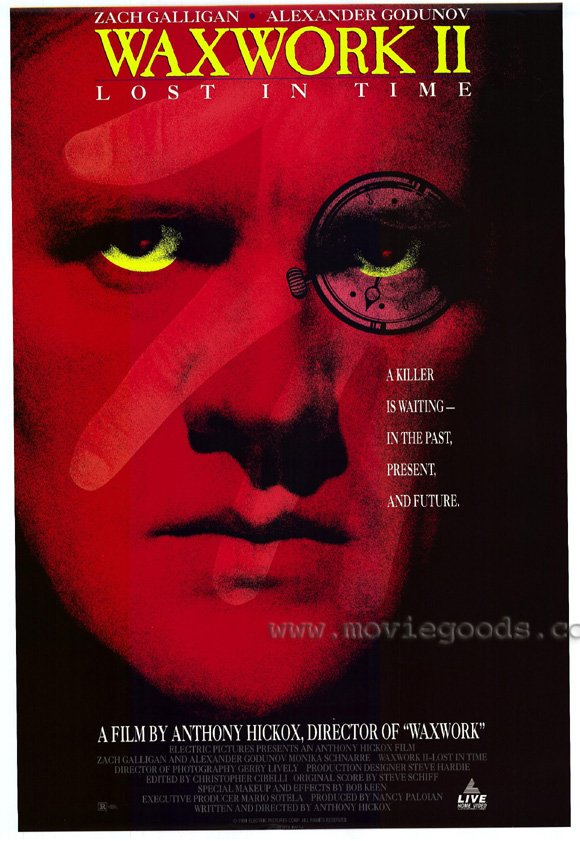

Mr. Hyde (Michael Viela) in Waxwork II.

Following the underrated Sundown: The Vampire in Retreat (1989), Hickox reunited with Galligan for Waxwork II: Lost in Time (1992), a film where his many movie influences are the story. I could not actually tell you what the plot is, apart from this: the film picks up from the final minutes of the original, despite the fact that Sarah is now played by supermodel Monika Schnarre instead of Foreman (whose off-screen romance with Hickox had ended). A severed hand stows away to Sarah’s home, where it murders her abusive stepfather (George “Buck” Flower) in a very Evil Dead II manner. The story then swings into a murder trial where her only hope is for Galligan’s Mark to prove that sinister supernatural forces are bent against her. Macnee returns in a cameo, having apparently recorded his final words in that short period between learning from Mark of the magical waxworks and getting killed inside (the man thinks ahead). He instructs Mark and an out-on-bail Sarah to seek out a time portal lurking behind a looking-glass in his home, which can be opened by moving pieces on an Alice in Wonderland chessboard. They pass through the mystical door into – well, a Hammer Frankenstein movie, which is where it becomes clear that the title of the film is a misnomer. A better title might have been Waxwork II: Lost in Other Movies.

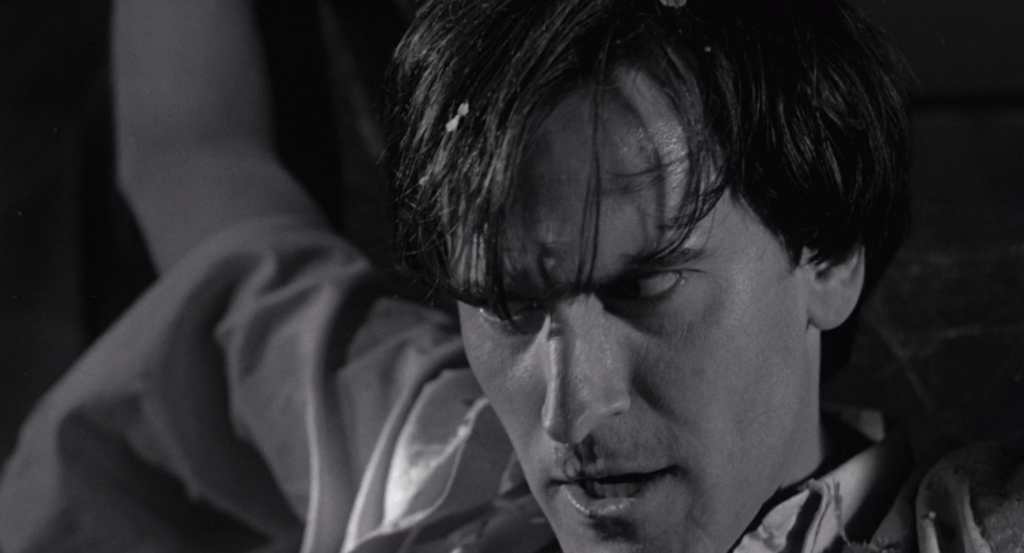

Bruce Campbell as the leader of a paranormal investigation that goes very badly.

Here Hickox’s direction has improved since his rough debut, though his script is a drunken mess, which I don’t mean as a criticism. By the end of the film I had no idea what was happening, what Mark was doing or had just done, who the villain really was or how they were supposed to get home. (I am told, though am not convinced, that a character named Scarabis and played by Alexander Godunov is important.) In a recurring joke, Mark delivers expository dialogue that only adds to our confusion: a tossed-off reference to the Loch Ness Monster is par for the course. It doesn’t help – and, again, I don’t really mind – that each time Mark and Sarah jump into their latest mini-adventure, they’re already dressed for their new roles and have adopted their personas, as if we’ve flipped channels and here we are, in some new movie’s final act. First up is the Frankenstein film, in which the doctor (Martin Kemp, The Krays) gets his head crushed by the monster, popping loose teeth and eyeballs like a Mr. Potato Head, and culminating in a brain bursting out of the skull, the camera tracking it as it hurtles toward Galligan Sam Raimi-style. The film switches to black-and-white for an extended riff on Robert Wise’s The Haunting, with Sundown co-star Bruce Campbell – just about to start filming Army of Darkness (1992) – taking the Richard Johnson role from the original, alongside Sophie Ward (Young Sherlock Holmes) and Marina Sirtis (Star Trek: The Next Generation). Walls breathe and bleed, the camera tilts and the image warps. Any doubt that this film is really more comedy-horror than horror-comedy should be erased by the extended scene in which a bound and partially flayed Campbell tries to maintain his composure under increasingly painful circumstances – an appropriate warm-up for the take on Ash that Raimi had in mind for Darkness, the broadest yet in that series. Hickox has fun bringing some color to the black-and-white, including a Shining nod with doors parting to fill a room with red blood.

David Carradine welcomes Zach Galligan to a medieval kingdom.

Sarah, with an Ellen Ripley haircut, finds herself in Aliens for a spell, allowing Hickox’s FX crew to build a giant gooey xenomorph to slaughter some astronauts. As the film unfolds, we also meet Jack the Ripper, Mr. Hyde, a suspiciously familiar shopping mall filled with zombies, and a poorly dubbed Godzilla knock-off. Unfortunately, the film stumbles with its take on sword and sorcery films (of the Roger Corman variety in particular) that bogs down the third act for far too long – it seems, for a time, that we might actually be expected to care about the characters and story, which of course we do not. But we do get a cameo from David Carradine, playing his flute from Circle of Iron (1978), and, well, the sight of Galligan in a Prince Valiant haircut (some unintentional foreshadowing, given that Hickox directed 1997’s Prince Valiant). Luckily, the climax, as with the original Waxwork, goes off the rails with calculated insanity, bouncing from one mini-movie to another, including an admirable recreation of Murnau’s Nosferatu with a cameo from Drew Barrymore. Both Waxwork films have been released on a double-feature Blu-ray as part of the Vestron Video line, and in the accompanying documentary The Waxwork Chronicles, Hickox reveals that his favorite parts of old monster movies were the finales, so Waxwork was intended to be a movie that consisted only of those moments. This sensibility of all highs and no lows comes closest to being realized in Waxwork II; and even if it’s not a completely successful experiment, the goofy side effects of the all-consuming enthusiasm are infectious, right down to the very early 90’s hip-hop music video (“Lost in Time”) that plays over the ending credits.