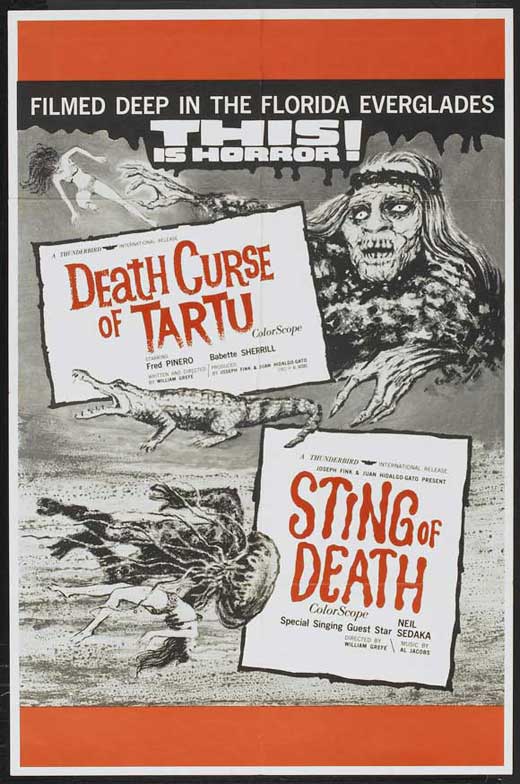

Arrow Video’s new box set He Came from the Swamp: The William Grefé Collection, celebrating the career of the Floridian indie exploitation filmmaker behind such films as The Wild Rebels (1967), Willard knock-off Stanley (1972), and Mako: The Jaws of Death (1976), kicks off with a swampy splash with its first disc, Sting of Death and The Death Curse of Tartu, which were released as a double feature in 1966 to take a gator-chomp out of drive-ins across America. The first film is a standard-template monster feature with outré value provided primarily by its choice of monster: a human who mutates into a Portuguese man o’war – a jellyfish – albeit one with groping hands and diver’s flippers for feet. The second film is more unusual: deep in the Everglades, an Indian spirit turns into various animals to kill those who venture onto his land. The acting is amateurish, the editing crude, the spontaneous eruptions of teenage dancing downright hilarious. But taken together, they’re oddball triumphs of low-budget gung-ho filmmaking, as Grefé literally throws his actors into the deep end – and, after them, snakes, sharks, and alligators. Much of the pleasure in watching them now is Grefé’s insistence on using real predators and shooting the vast majority of footage in authentic locations. (The director would later apply his skill at working with live animals on the sets of Live and Let Die.) When an actress splashes around while fleeing a jellyfish monster, you half expect her to emerge covered in leeches before Grefé calls “cut.”

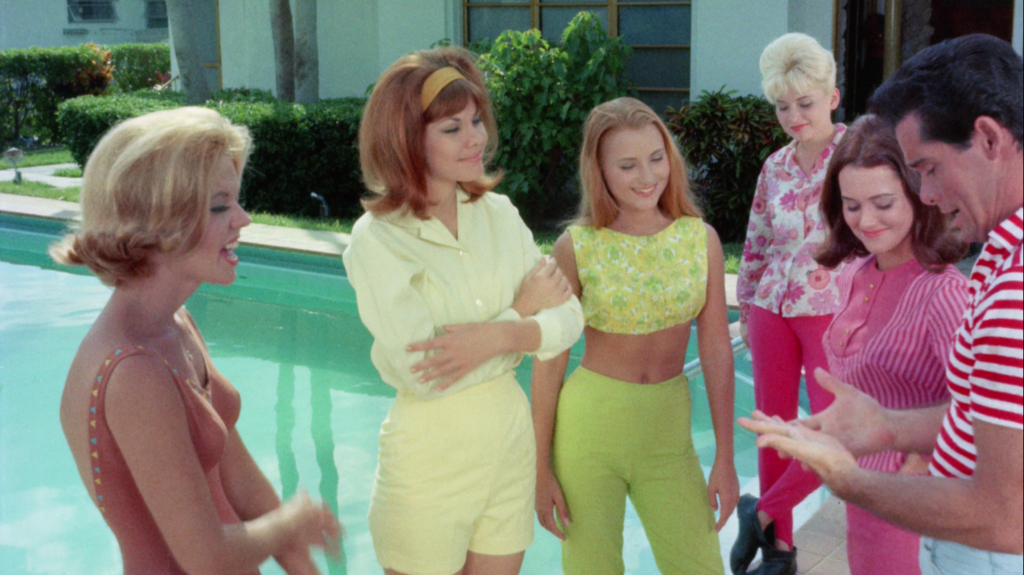

Teenagers getting ready for a pool party (and “The Jellyfish Song”).

Sting of Death is the more purely enjoyable of the two films, a brisk and outlandish 80 minutes which begins with a bikini-clad sunbather killed by some kind of swamp thing, then dragged underwater through the opening credits. A marine biologist (Jack Nagle), who has an extremely distracting black spot in the middle of his head (a recent injury, he tells us), welcomes his daughter’s friends to his island home, where they gather around a swimming pool and meet his hunky young researcher friend (Joe Morrison, of Grefé’s earlier films The Checkered Flag and Racing Fever), as well as the disfigured Egon (John Vella, The Wild Rebels). Egon is hyper-sensitive to any mockery over his looks, and also strangely insistent that jellyfish – the subject of their research – can grow to much larger sizes than previously known. Unbeknownst to them, in his spare time Egon heads out to a secret cavern lair outfitted with mad science equipment and transforms himself into a giant humanoid man o’war – the actor’s head still visible inside his balloon-like helmet – before taking revenge on those who would insult him. But in the meantime, we’re treated to Neil Sedaka tunes including “The Jellyfish Song,” which accompanies the teenagers’ pool party and much Beach Blanket Bingo-style dancing. (The teens also take time to insult the Beatles; and it’s true, the Beatles never wrote anything like “The Jellyfish Song.”) The good times end when a boat ride sends the group into the water, where they’re attacked by some very fake-looking jellyfish. Then the mutated Egon begins stalking them, first by lurking in the swimming pool next to their dancing feet (how he’s not spotted is anyone’s guess), then by creeping up to a busty blonde while she takes a shower, because a bit of Hitchcock will surely class up this joint.

Shower stalking in “Sting of Death.”

Throughout, Grefé enjoys taking us on trips through thick reeds on an air boat or showing us divers searching with flares underwater. The climax, in which Morrison fights the jellyfish-man while gripping his sparking flare amidst the green, purple, and blue hues of the secret cavern – while the damsel in distress cowers amidst inexplicable human skulls – is the precise pulpy horror endpoint one desires out of this third-tier Creature from the Black Lagoon. I should mention that, although these are new 2K restorations (from a 35mm negative for Sting of Death, and a 16mm negative for Death Curse of Tartu) and the colors truly pop in Sting, the elements for these very rare films are imperfect: the sound is harsh and the films reflect flickering and various forms of damage on the negative. They both look like drive-in films that have travelled the country for years and arrived in your home showing all the wear. I don’t mind that, and in many ways it heightens the experience; these films need nothing further but popcorn and beer (or perhaps ads reminding you to check out the concession stand between films). And Death Curse of Tartu, which was made, Corman-style, for the sole purpose of accompanying Sting of Death into drive-ins, has an even rougher, almost cinéma vérité look for its location footage – having less damaged elements would not benefit it all that much, and that beer will help you get through the seemingly endless scenes of explorers wandering through the Everglades, which seem to have been inserted to pad out the film and allow teens plenty of time to make out in the back seats of cars.

An Indian zombie lies inside a secret crypt in “Death Curse of Tartu.”

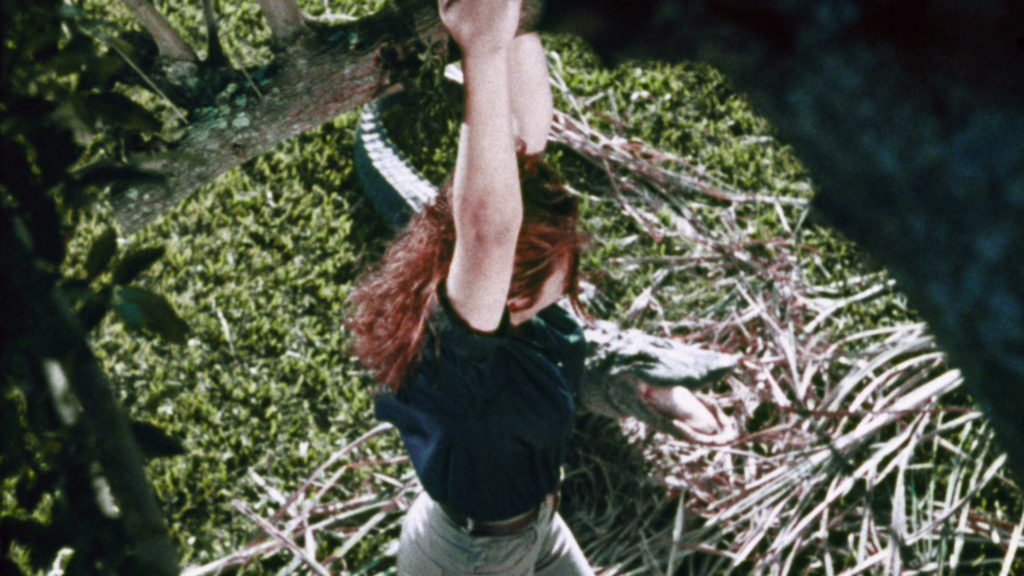

If Death Curse has a very different feel from Sting of Death, that’s likely due to the scratchy field recording of Indian chanting and drums that often interrupts the soundtrack, indicating that the curse is about to reach out and attack one of the Everglades interlopers. Grefé cuts to a dark underground crypt where a man in skull makeup (Doug Hobart) opens his eyes and rises from his coffin. (Cultural accuracy is not the film’s strong suit.) He then transforms into various bloodthirsty animals – predicting the 70’s wave of nature-run-amok movies. Our hero, alas, is a rather obnoxious know-it-all archaeologist (Fred Pinero) who bosses around his wife (Babette Sherrill) and four teenagers as he takes them on a swampy search for his missing friend, already murdered by the spirit Tartu. The four teens want only to make out, roast marshmallows, and dance, which is all well and good until one of them is eaten by a shark (that is, Tartu). Shortly their air boat is scuppered by the sinister force – although we have to take their word for it, because the budget won’t allow for damaging such a vehicle – which creates the problem of having to send someone back for help, a long walk downriver and vulnerable to the wrath of Tartu. Without question the film’s highlight is an attack involving a live, very large alligator on a screaming girl dangling from a tree. (The gator violently wrestled Grefé on location after he unsuccessfully tried to convince his actress that it was harmless with its mouth tied shut.)

Alligator attack.

Grefé and director Frank Henenlotter (Basket Case) provide audio commentary for both films. The disc is also accompanied by two featurettes directed by the reliably excellent Daniel Griffith: “Beyond the Movie: Monsters-a-Go-Go!” in which author and historian C. Courtney Joyner recounts the history of rock ‘n’ roll monster movies of the 60’s, and “The Curious Case of Dr. Traboh: Spook Show Extraordinaire,” an interview with Tartu‘s monster, Doug Hobart, who hosted a string of successful “spook shows” in theaters in the 50’s as “Dr. Traboh.” This latter featurette is a priceless history of a lost art form, which presented films alongside elaborate, sometimes titillating, sometimes gory live theater performances for appreciative audiences of screaming kids. The box set also contains Grefé’s The Hooked Generation (1968), The Psychedelic Priest (1971), The Naked Zoo (1970), Mako: The Jaws of Death (1976), Whiskey Mountain (1977), and They Came from the Swamp (2020) a new documentary on the director, along with hardcover liner notes. More to come, maybe!