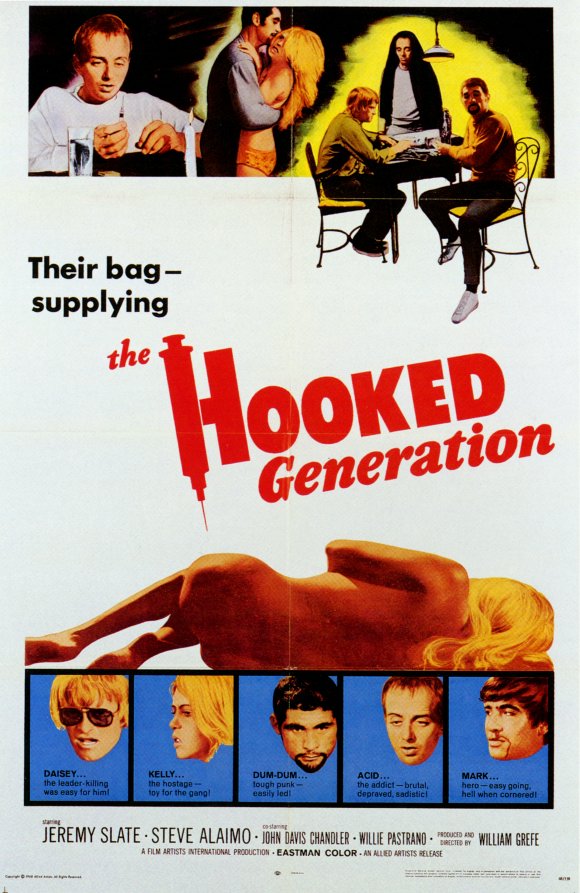

The second disc in Arrow Video’s box set He Came from the Swamp: The William Grefé Collection switches focus from pulpy horror to the briefly thriving genre of hippiesploitation. (The first disc, containing Sting of Death and Death Curse of Tartu, is reviewed here.) The judgmental title of The Hooked Generation (1968), however, is a bit misleading. Although on the whole the film delivers a message that drugs will lead you to degradation and death – a frequent ingredient in this subgenre, such as with the camp classic Psych-Out (1968) – the case study here is far from typical. Set, of course, in Grefé’s Floridian stomping grounds, the story ostensibly charts trafficking from Cuban drug runners to rock clubs and finally a decrepit plantation occupied by free-loving hippies and catatonic addicts. Yet any sense of verisimilitude is washed out to sea quickly. A raw opening credits sequence depicts the unhinged Acid (John Davis Chandler, Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid) preparing to shoot up heroin on the boat belonging to Daisey (Jeremy Slate, The Born Losers), before soldiers of Fidel Castro arrive with a cache of drugs. Deciding that their price is too high, Daisey allows the Cubans to lower their guard by asking them to join him for a smoke, then shoots their leader with a spear gun. Slaughtering the rest of the soldiers and leaving their bodies to burn on the Cubans’ boat, Daisey and his men take their loot downriver only to encounter the Coast Guard. A shootout ensues, the Coast Guard officers are slain, hostages are taken, and a flight begins through swamps and drug dens while police cast their dragnet.

Jeremy Slate does his best White Heat-era James Cagney in The Hooked Generation.

Despite a psychedelic rock score by Chris Martell and the Odyssey, frequently The Hooked Generation feels more like a psychopaths-take-hostages crime drama than a counterculture exposé. But when Grefé (who co-wrote the screenplay) turns his sights to our protagonists’ ultimate chaotic fates, the film becomes much more interesting. A pit stop in an Indian village sees Acid chasing a young woman to a riverside, where the drug-addled young man holds her head underwater just to teach her a lesson – then becomes distracted by a bird flying overhead. For the first time in the film, Grefé allows a moment of stillness and peace, all while a woman is accidentally drowned. Acid proceeds to rape her (off screen), still oblivious to the scale of his crime when he returns to his companions. His final shoot-out in the plantation drug den is accompanied by a lysergic mental fracturing, as Grefé nightmarishly replays the last minutes of his life from different angles, bouncing back and forth in Acid’s head while he bleeds out. The film concludes with a sustained hostage stand-off in the swamps as Daisey and his partner Dum Dum (Willie Pastrano) – the latter nicknamed for the dumdum bullets he carves – try to hold back the police. But, apart from Slate’s sweaty and committed performance, nothing really gels until the final moments when Daisey, jabbed in the neck with a needle by one of his hostages, OD’s while stumbling face-first into the water. Grefé mirrors the drowning of the Indian girl by studying Daisey’s submerged face while he silently dies.

John Darrell takes some acid-spiked Coke to become The Psychedelic Priest.

The Psychedelic Priest (1971), originally entitled Electric Shades of Grey for a (quite good) song that features prominently on the soundtrack, is a more authentic slice of hippiesploitation. As Grefé tells it, he was summoned to California by producer/director Stewart Merrill to make a film about a priest experiencing youth culture, at which point Merrill revealed he had no screenplay. Grefé indulged him by proceeding to improvise the entire 16mm film alongside an inexperienced, often plucked-from-the-sidewalks cast. Yet all this effort was for naught; after Merrill burned a bridge with a distributor, the film went unreleased for decades, until at last Something Weird resurrected the movie for a 2001 DVD release. The priest in question (John Darrell) is introduced lecturing some college kids who are skipping class and smoking pot on the campus lawn. They offer him a Coke laced with LSD, and during his bad trip he takes shelter in a church that becomes nightmarish. This leads to Darrell promptly dropping out of society Timothy Leary-style, driving to Los Angeles and picking up a hitchhiker who eventually falls in love with him. They travel the country, but his rejection of her proclamation of love, her subsequent tragic death, and the murder of a Black traveling companion at the hands of racist small town cops, lead the priest to hard drugs and disillusionment. Eventually, he finds his way back to God after receiving inspiration at a church revival.

Travelling companions in The Psychedelic Priest.

The Easy Rider template is obvious, from the cross-country road trip to the brutal encounters with prejudice (including against long-haired hippies), but the improvised dialogue and amateur performances are front and center. On the one hand, they saddle the film with tonal inconsistency from beginning to end, such as when our protagonist comes across as almost indifferent to the hate crime murder of his friend just one scene prior. The late film introduction of a sleazy private detective feels just as random. But The Psychedelic Priest has plenty of appeal as a time capsule of a specific time and place, namely southern California in the early 70’s, as the culture of peace and love became increasingly disillusioned with the violence of Altamont ’69 in the rear view mirror. With the plot being hardly more than a shrug, it’s easy to settle in and enjoy the people watching, particularly with shots stolen at music festivals and some remarkable footage of confessions given by microphone at the climactic church service. You also get to see our psychedelic priest wandering past roadside dives and vintage scuzzy massage parlors. This is a slight, often crudely assembled little movie, but it’s also a window into a fascinating, fleeting American moment. As with the previous disc reviewed in Arrow’s box set, this is not reference quality material: the sound for both films is rough, with The Hooked Generation‘s dialogue bearing the brunt of the abuse. Instead, the appeal is the preservation of a pair of exploitation items that could otherwise be easily overlooked. A pair of interviews with author/film historian Chris Poggiali provide additional context (intriguingly, he compares Psychedelic Priest to the Billy Graham-produced films of the 50’s and 60’s), and the older audio commentaries with Grefé and Frank Henenlotter are ported over.