2021 is the 10th anniversary of Midnight Only. To mark the occasion, this imaginary, rat-infested, leaky-roofed theater is raising the curtain on historically important midnight movies.

“When you were seven yards from the corral, my rabbits began to die.”

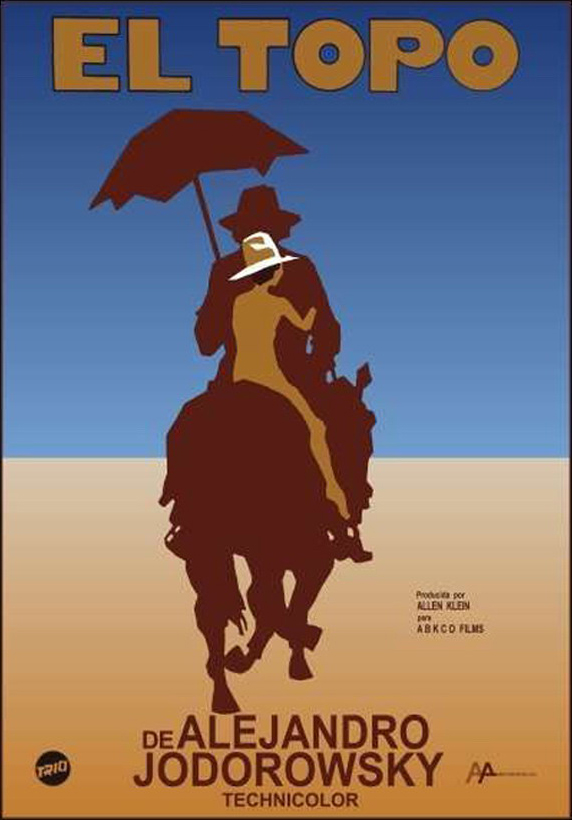

Alejandro Jodorowsky’s El Topo (1970) is widely regarded as the first midnight movie. Impressed by the psychedelic mind-blower, Ben Barenholtz booked it for the Elgin Cinema on 19th and 8th Ave in New York City in December 1970 for midnight screenings, where it was an immediate counterculture hit, running for six months straight in the midnight slot, seven nights a week, perplexing critics but drawing celebrities into clouds of pot smoke to gaze in awe before surrealistic images of grisly violence, blunt sexuality, and mysticism. John Lennon persuaded his manager Allen Klein to buy the distribution rights, and the soundtrack (credited to Jodorowsky) was released on the Beatles’ Apple Records. From thence forward, exhibitors across the country began to slot in midnight screenings of underground or independent movies, or camp revivals of bizarre and forgotten movies, all to sell tickets to mind-altered night owls seeking an El Topo style buzz. I first became aware of the film by paging through Midnight Movies by J. Hoberman and Jonathan Rosenbaum in my local library, mesmerized by the fantastically surreal images of a legless man astride an armless man, both semi-nude, in a stark desert landscape before a gunfighter dressed completely in black. The film was not available anywhere. At the time, Klein and Jodorowsky were feuding long distance, and Klein refused to permit its release in the U.S. (In a belated happy ending, the feud was amicably resolved a few years before Klein passed away.) When I was attending grad school I lived within walking distance of the famous Scarecrow Video, and was at last able to watch the film – via a Japanese VHS, censored to disguise any visible pubic hair. Drawn in by the incredible images, what impressed me the most was that I was in the presence of a true storyteller. On one level, the film is a rapid succession of big moments, each one more outrageous than the last. But the ideas behind the images accumulate and evolve. The characters transmogrify and invert. Jodorowsky is telling a new kind of myth.

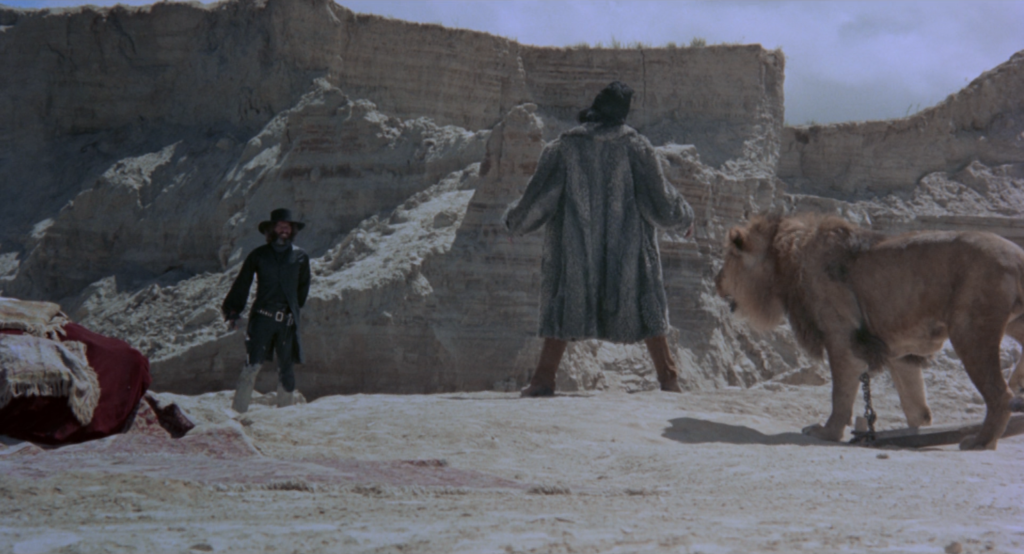

El Topo (Alejandro Jodorowsky) confronts the Second Master (Juan José Gurrola).

Since then, I’ve seen El Topo many times, including once on the big screen. Over time, my admiration for the film waned somewhat as I became far more interested in the works Jodorowsky produced after that – mostly in the realm of the graphic novel, where his imagination could roam more freely (independent of budget constraints), where he began to achieve more sophisticated artistic ends, and where he matured as a creative force – though he never quite mellowed. Funny thing, this most recent viewing (courtesy last year’s incomplete but nonetheless impressive Alejandro Jodorowsky Blu-ray box set from Arrow Video and Allen Klein’s Abkco). I felt as I did the first time I saw it. I was absorbed by the images and swallowed by the fable. There is much about El Topo which is naïve, or chauvinist, or simplistically symbolic. The soundtrack can be hypnotic, but it can also be grating. The performances are amateurish. Jodorowsky – who from 1967-1973 honed a guru-like persona through his Panic Fables newspaper comic strip – can seem a bit too self-impressed. But as the film progresses, the potent collage of ideas and images snowball. The ending massacre and ritualistic suicide, all of it apocalyptic and broad-strokes tragic, becomes something bigger than Jodorowsky’s outsized persona, something that vibrates with genuine terror like the cicada-style noise that frequently rattles the soundtrack. By then, the woozy, sometimes frenzied tenor of the storytelling has baked in deep, as with a scene set in a church where members of the congregation hold a pistol to the head, pull the trigger, and declare “miracle!” when they hear the hollow click – until an enthusiastic little boy leaps suddenly into the shot, seizes the pistol and – another of Jodorowsky’s jarring jump cuts – blows his brains out.

The slaughtered village.

El Topo announces that it’s not a film for the weak of stomach from the very start. Following its indelible opening scene, in which a nude child buries in the sand his first toy and his mother’s picture, he rides with his gunfighter father into a village literally awash in gore. A body is impaled in the air. A river of blood flows through the middle of the town. Bodies clad in bloodied white garments are strewn across the dirt. Hanging corpses swing from rafters with a heavy creak. The walls are painted red. This is the Sam Peckinpah Western as horror movie. To avenge this evil, El Topo (“the Mole”) pursues the Colonel (David Silva) and his perverted bandits, who are in the process of humiliating some Franciscan monks. El Topo dispatches them – castrating the Colonel – and rescues a woman whom he names Mara, “Bitter Water,” after a parable he describes of Moses transforming rank water to taste sweet. In fact, El Topo – dressed from head to toe in black, with his wide-brimmed hat and a gun on each hip – reenacts the same miracle and others while they ride through a vast empty desert, shooting rocks to create springs, finding eggs in the sand. They grow delirious and possessed. Persuaded by Mara, he embarks on a quest to find and topple four Masters who live in this desert. He draws a spiral map in the sand, describing how they can be found while walking a circular path. Though his confrontations with these mysterious figures bear some traces of Sergio Leone, Jodorowsky’s brilliant stroke is to make them Zen masters, challenging El Topo’s motivations and psyche more than the quick-draw skills he demonstrated against the Colonel’s bandits. One looks like George Harrison, proving he’s impervious to bullets by simply letting them pass through his bare chest. Another is accompanied by a lion and a fortune-teller who squawks like a bird as she dies. The third lives among a thousand rabbits. The fourth, a frail old man, stops El Topo’s bullets with a butterfly net.

The decadent town from the film’s second half.

Jodorowsky’s methods and outlook were shaped by his years with the Panic Movement, a manifesto-driven post-Surrealist artistic collective that emphasized the violation of boundaries and taboos. Formed in Paris in the early 60’s with Roland Topor and Fernando Arrabal, the movement directly informed Jodorowsky’s first film, the waking nightmare Fando y Lis (1968). Shot in black-and-white in a rocky wilderness similar to El Topo‘s, the film adapted Arrabal’s play (from memory rather than from a screenplay, as Jodorowsky has claimed) about young Fando carting his paraplegic lover Lis toward a promised land, like an atheist’s Pilgrim’s Progress, an adults-only cry of despair stretched across 90 often punishing – sometimes dazzling – minutes. (Arrabal would in 1971 direct the powerful but similarly bleak Viva La Muerte, which bore enough of a surface resemblance to El Topo to also get booked on the midnight movie circuit.) El Topo is credited to Producciones Panic, and indeed has one foot in Jodorowsky’s past, an assault on complacency. But it’s also a colorful comic book, a pulp fantasy like the ones Jodorowsky grew up reading in Chile. Despite its violence, it’s digestible – even, in its Jodorowskian way, accessible. By having his labyrinthine Zen parable use the language of a Hollywood Western – making it “an Eastern,” as he coins it in Stuart Samuels’ 2005 documentary Midnight Movies: From the Margin to the Mainstream – Jodorowsky captured not mainstream success but a loyal cult following that would allow him to make the wild science fiction opus The Holy Mountain (1973). He also invented the Acid Western, which may have some antecedents (I’m thinking of the Prisoner episode “Living in Harmony” from 1967), but would briefly live in the 70’s with films like Zachariah (1971) and Robert Downey Sr.’s Greaser’s Palace (1972).

Robert John as El Topo’s son.

If you follow Jodorowsky’s cross-media work that comes after, you will identify the children of El Topo. See Endless Poetry (2016) for a refracted retelling of the beautiful woman with dwarfism who falls in love with El Topo. His 2002 novel Albina and the Dog-Men features men transformed by lust into literal dogs, foreshadowed by the Colonel’s men in El Topo falling to all fours and barking at his feet. But most notable is his recurring personal and artistic interest in the psychological damage fathers can do to their sons. This becomes a dominant theme in what might be his greatest achievement in the graphic novel format, the multi-generational SF saga The Metabarons (1992-2003), as well as in his films Santa Sangre (1989) and The Dance of Reality (2013). In the latter film, a partly fictionalized autobiography of his childhood in Chile, Jodorowsky casts his son Brontis Jodorowsky – who plays his son (at age seven) in El Topo – as his real-life Russian immigrant father. The Dance of Reality is the director’s masterpiece, but he never quite let go of El Topo. He wrote a screenplay to a sequel and in the early 2000’s attempted to get it going despite the rights issues from his Klein feud; at one point he suggested circumventing the problem by calling it The Sons of El Toro, the mole now become a bull. Ultimately he turned the screenplay into a graphic novel with art by José Ladrönn. The story continues the theme of El Topo‘s second half, in which the gun master’s legacy of violence and surprising sainthood leaves deep scars upon his offspring – here riffing upon the Biblical story of Cain and Abel. As with his plans for an adaptation of Dune (the topic of 2013’s Jodorowsky’s Dune), it’s a shame it was never brought to the screen, but the original El Topo still retains that charge that drew its original audience, the thrill of disbelief at what we’re seeing – that someone, on such a miniscule budget, could deliver and deliver and deliver on such unruly spectacle.