2021 is the 10th anniversary of Midnight Only. To mark the occasion, this imaginary, rat-infested, leaky-roofed theater is raising the curtain on historically important midnight movies.

“The motion picture you are about to witness may startle you. It would not have been possible, otherwise, to sufficiently emphasize the frightful toll of the new drug menace which is destroying the youth of America in alarmingly increasing numbers. MARIHUANA is that drug – a violent narcotic – an unspeakable scourge – the real Public Enemy Number One!”

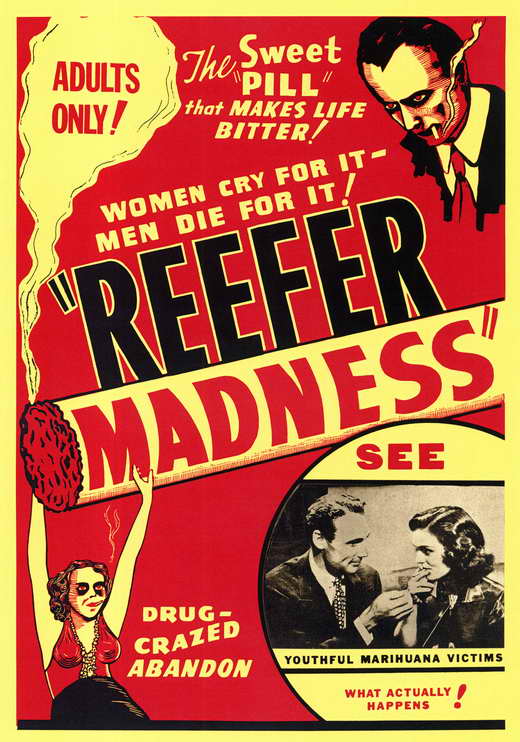

Tell Your Children (1938) was just one artifact of a rise in hysteria toward the drug in the 1930’s. The movement was driven by Federal Bureau of Narcotics’ Harry Anslinger and his racist campaign to criminalize its use. (Among his many absurd quotes: “There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the U.S., and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos and entertainers. Their Satanic music, jazz and swing result from marijuana use. This marijuana causes white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes, entertainers and any others.”) Appropriately, the film begins with a group of concerned white mothers listening to a lecture from school principal Dr. Carroll (Jose Forte), who explains that marijuana is “more deadly” than heroin. Later in the film a case is mentioned where someone “under the influence of the drug…killed his entire family with an axe,” an apparent reference to an October 16, 1933 incident in Florida, which was later used by Anslinger as an example of the deadly impact of cannabis because the killer, “Dream Slayer” Victor Licata, was a pot smoker. Absorbing the Anslinger propaganda as fact, Tell Your Children – originally produced by exploitation filmmaker George A. Hirliman before being re-edited into a salacious feature film by Dwain Esper – became a roadshow hit, traveling the country outside the perimeter of the Hays Code, and playing as The Burning Question and Doped Youth (and possibly Sex Slaves) before it became Reefer Madness in 1940. Under this title it entered into kitsch legend.

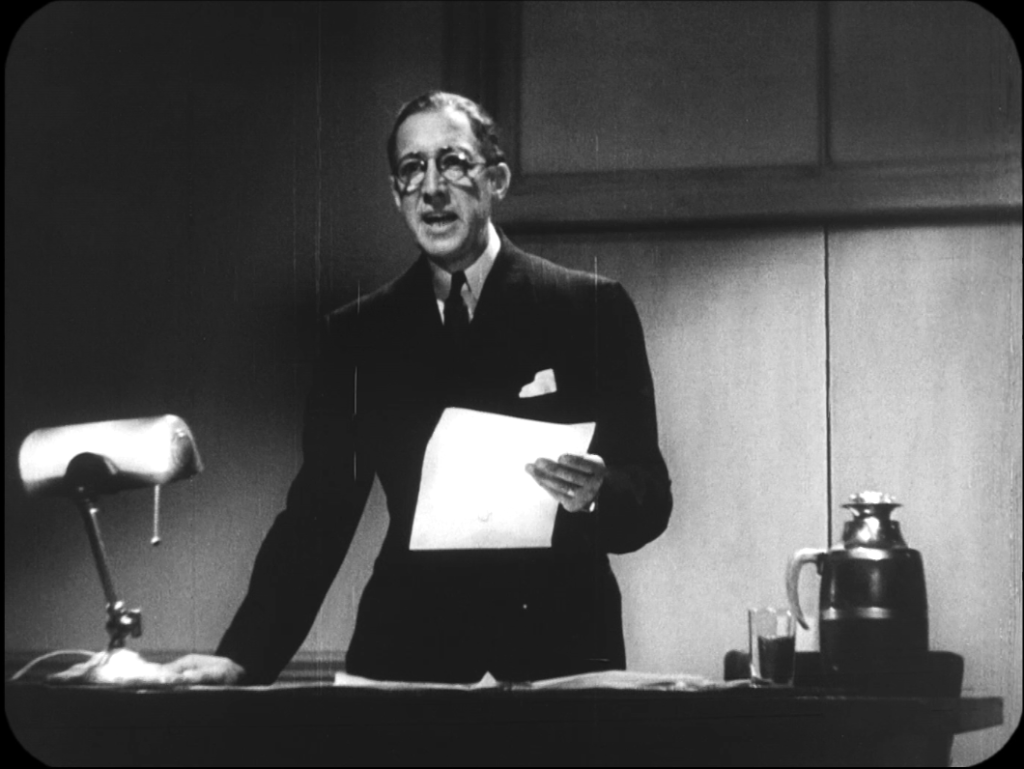

Dr. Carroll (Josef Forte) warns that reefer could corrupt your children…or yours…OR YOURS!

In the 70’s, college campuses and venues specializing in midnight screenings resurrected Reefer Madness, following a successful benefit revival sponsored by the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML). The film’s newfound notoriety arrived – alongside other stoner midnight movies like The Terror of Tiny Town (1938) and Cocaine Fiends (aka The Pace That Kills, 1935) – at the dawn of ironic movie watching. It was the path that led to the Medveds’ Golden Turkey Awards books and Mystery Science Theater 3000. Eventually Reefer Madness became a camp musical, which was adapted into a TV-movie with Alan Cumming, Kristen Bell, and Neve Campbell in 2005, and a colorized version of the original film has been riffed more than once by Rifftrax. Its public domain status has made it nearly as ubiquitous as Night of the Living Dead. The appeal of the film is obvious, and right there in its gimmick of a (re)title. White, straight-laced, glittering-teethed youths are drawn one by one into an apartment where they succumb to the devilish allure of cannabis, and their lives are destroyed spectacularly. This is accomplished mostly through piano playing and dancing. Then just a little bit of heavy petting. And, finally, manslaughter.

Jazz music from a reefer fiend.

The drug pushers are Mae (Thelma White), Ralph (Dave O’Brien), and Jack (Carleton Young). Though the jaded Mae has qualms, Jack and Ralph aggressively try to lure teens up to their apartment where the jazz music plays freely and marijuana cigarettes are on offer. “If you want a good smoke, try one of these!” The effect is instantaneous: greedy puffs, Joker grins, insane giggles. And always the piano playing. “Faster! Faster! Play it faster!” Into this drug den are pulled Jimmy (Warren McCollum) and Bill (Kenneth Craig). Jimmy agrees to give Jack a drive, and when he asks for a cigarette on the trip back, accepts a joint. He slams on the gas, veers back and forth on the busy streets, and runs a stop sign, flattening a pedestrian. Bill is in a literal Romeo and Juliet relationship with the virginal Mary (Dorothy Short) – they’re rehearsing the play together as an excuse to lock lips – but when he agrees to visit Jack and Mae’s apartment, his moral decline is rapid. He sleeps with the sultry Blanche (Lillian Miles) while high; at the same time, Mary, who’s come looking for him, is sexually assaulted by Ralph. Stumbling into the scene, Bill hallucinates that it’s consensual and attacks Ralph. Jack arrives on the scene with a gun, and in the scuffle accidentally shoots Mary. Jack successfully frames Bill for the murder. Such are the wages of marijuana sin.

A suicidal defenestration.

The cheap sets, simplistic characterizations, mild sleaze (like a lingering shot of a woman pulling up her nylons), and violent moral consequences – the film ends with a suicidal leap through a window – are all hallmarks of early exploitation film. Both the lecturing judge in the climactic trial and the bookending Dr. Carroll, speaking more or less directly to the audience when they lecture about the mortal danger of MARIHUANA, are thin excuses to deliver the lurid thrills the audience is seeking, and which the sensationalistic posters promised. Joe Dante, who in the late 60’s assembled the clip show film The Movie Orgy for college campuses with the same ironic approach as the revival of Reefer Madness, later created a pitch-perfect parody of this kind of preachy “educational” picture with his segment “Reckless Youth” for Amazon Women on the Moon (1987). In the short, the title card is almost identical to that of Reefer Madness‘ (“Formerly Tell Your Children“), squeezing into the corner of the frame “Formerly Are These Our Loins?” and crediting the film to Dwain Kroger (as opposed to Dwain Esper). Warning of something which can only be politely referred to as the “Social Disease,” Dante’s film follows the decline of Iowan country girl Mary Brown (Carrie Fisher), who, after winning a beauty contest, is corrupted by a theatrical agent and taken to his apartment. Stripped down to her underwear and sitting on his knee while topless women bat a balloon back and forth behind her, she remarks, “Gee whiz, my first sophisticated New York party. Which one is Cole Porter?” Dante’s film is every bit as “educational” as Reefer Madness – arguably even more so.