Well! It’s been a minute! As I return to a hopefully more regular schedule, I’m initiating a new feature, the Midnight Video Dispatch. At the start of the pandemic, I began work on building a video store in my basement. Naming it Midnight Video (after this website), it now houses my video collection using cast-off video store shelves from a shuttered Family Video. This series will use the Midnight Video framework to spotlight staff picks, new releases, and recommended titles from different categories of the “store.”

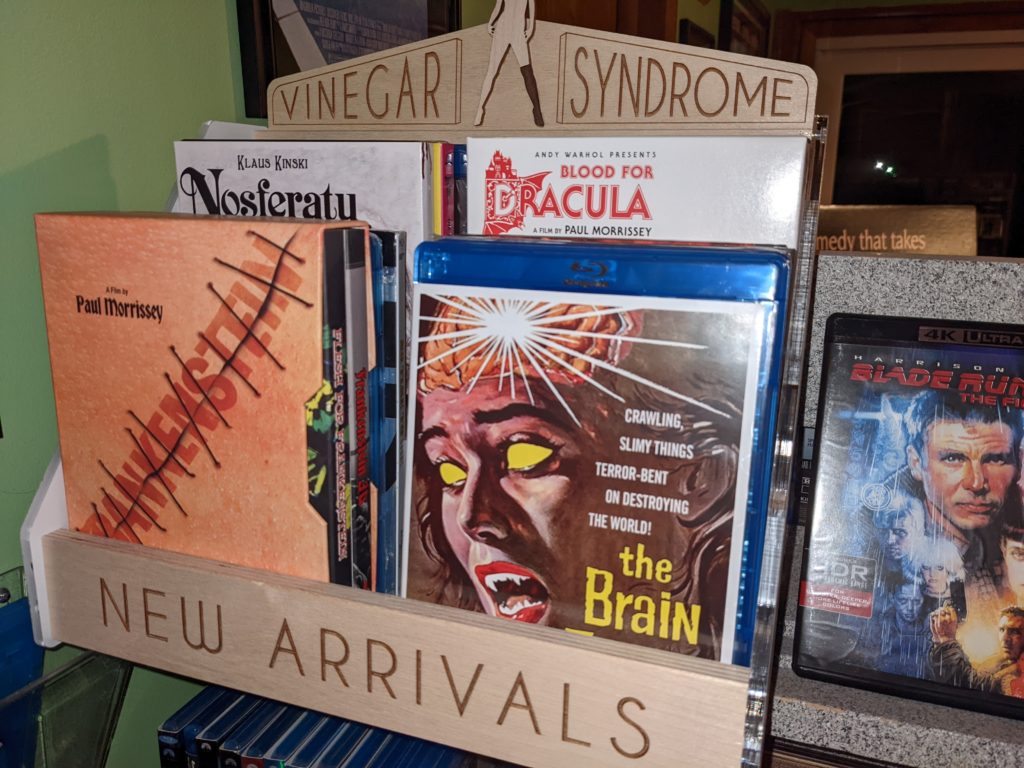

New Arrivals

(Or new-ish, since some of these have been out for many moons.)

Over the years, Vinegar Syndrome (from whom I purchased the lovely “New Releases” box displayed above, as part of their last Black Friday sale) has split their time between releasing adults-only titles of the 70’s and early 80’s with all kinds of other exploitation-themed whatsits, always with the most consistently high-quality presentations on the market. As their brand has expanded in popularity, they’ve been able to acquire some higher profile cult titles, including their late-2021 release of Andy Warhol’s – er, scratch that, Paul Morrissey’s Flesh for Frankenstein (1973). The film has been unavailable for quite a while, although it was Criterion’s spine #27, long out of print on DVD. Yes, those were the days when Criterion would actually release something as unapologetically lowbrow as Flesh for Frankenstein. Though I had seen its famous follow-up, Blood for Dracula (more on that in a second), I never quite got around to this one before it became something one had to really make an effort to find. And yet Blood for Dracula made a big enough impression on me, when I rented it on VHS in the 90’s, that I bought a soundtrack CD that included Claudio Gizzi’s score for both films. I listened to that CD over and over for years, having to rely on imagination to put pictures to Frankenstein‘s gorgeous themes.

Well, all those years – even after reading about how over-the-top the film was – I wasn’t imagining that Gizzi’s delicate, sensitive, romantic gothic orchestrations accompanied this bad-taste wonder. That contrast just makes Morrissey’s campy horror comedy all the more ridiculous. Udo Kier, who was Nicolas Caging his roles in horror films at least a decade before Nicolas Cage began Nicolas Caging, plays Dr. Frankenstein as an overtly insane necrophiliac. He’s married to his sister (Monique van Vooren), a minor detail which took me a while to grasp, before slapping my head and saying, Well of course he’s married to his sister. It’s that kind of film. She’s sexually unsatisfied since he spends so much time in the lab, fetishizing every aspect of his surgical procedures, so she takes their latest servant as a lover. He’s played by Joe Dallesandro (Flesh, Trash), who, like Morrissey, was a veteran of Andy Warhol’s Factory scene. Dallesandro has a thick New York accent that blends like oil in water in this Eurocult castle: Kier speaks with an at-times impenetrable German accent, while most of the cast is Italian. The film gleefully reinterprets Mary Shelley as grand guignol by way of Pink Flamingos. It’s a midnight movie through and through, and originally played in 3D, dripping organs dangling right in your face. In fact, one of the reasons why I put off this movie for so long was the desire to see it as it was originally presented, which is something Vinegar Syndrome’s deluxe set remedies. (If you don’t have a 3D projector or TV set, a red/blue anaglyph presentation is available, and glasses are included.) Also inside the comprehensive package is a 4K and Blu-ray, for those who haven’t made the UHD upgrade yet. (I made the leap when pushed off the cliff: my beloved plasma TV died a year ago.) This is an outrageous, endlessly quotable film, though I still prefer its semi-sequel…

Severin Films had a banner year in 2021, culminating in the mammoth All the Haunts Be Ours compendium of folk horror films (built around the documentary Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched: A History of Folk Horror, directed by the box set’s curator, film scholar Kier-La Janisse). I’m not writing about that here simply because I haven’t cracked it open just yet. So, with that massive exception aside, my favorite release of theirs in 2021 was Andy Warhol’s – scratch that again, no idea why I keep making that mistake – Paul Morrissey’s Blood for Dracula (1974). Reuniting the director with Kier, Dallesandro, and composer Gizzi, this is the superior film, though it also takes less of the John Waters approach to its satire. I mean, I wouldn’t call it subtle. Kier’s anemic Dracula can only survive on virgin blood, but in the swinging 1920’s virgins are harder to come by. He travels to Italy in the mistaken belief that a Catholic country will have virgins in greater supply. Perceived as a wealthy bachelor, he’s eagerly hosted by a landowner played by Italian neo-realist icon Vittorio De Sica, his wife, and their three beautiful daughters, one of them Suspiria‘s Stefania Casini. Unfortunately for the Count, the daughters are being seduced one by one by the hunky gardener (Dallesandro). Featuring a cameo by Roman Polanski and a fantastic Gizzi score, which plays over one of 70’s cinema’s most memorable opening credits sequences, this is essential Eurocult and a lot of fun. Severin’s package is the perfect companion to Vinegar Syndrome’s, with a UHD, Blu-ray, and interviews with Morrissey (amusingly bitching that Warhol did nothing on the films, which of course were released in many regions as Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein and Andy Warhol’s Dracula), Kier, and others.

Speaking of the lord of vampires, Severin has also released to Blu-ray the overlooked Klaus Kinski film Nosferatu in Venice (1988). A sort of belated, bootleg sequel to Werner Herzog’s Murnau homage, Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), this was a hugely troubled production thanks entirely to the hugely troubled Kinski. The film’s completion was delayed, went through multiple directors, and was repeatedly undermined during shooting by the notoriously difficult actor, details of which are discussed in the feature-length documentary featured on the disc, Creation is Violent: Anecdotes from Kinski’s Final Years. This is an essential work, featuring interviews with those who knew and worked with (or, as necessary, against) Kinski during the last six years of his life. Principally covering the production of Creature (1985), Commando Leopard (1985), Revenge of the Stolen Stars (1986), Crawlspace (1986), Nosferatu in Venice, and Kinski’s only directorial effort, the disastrously received biopic Paganini (1989), the documentary creates a surprisingly complex portrait of Kinski that feels much more complete than Herzog’s otherwise entertaining doc My Best Fiend (1999). Here are the expected harrowing tales of Kinski sabotaging his directors, including a very funny Ulli Lommel recounting how he had to turn Kinski’s character in Revenge of the Stolen Stars into a ghost just to accommodate the egregious continuity errors the actor deliberately created. But these anecdotes share space with tales of his physical and sexual abuse both off and on set, actresses recounting, with both horror and gallows humor, how they tried to defuse intensely inappropriate situations (some of his victims, unfortunately, could not). And these anecdotes share space with more tender recollections of Kinski, including from a California postal worker and his daughter, both of whom shared an unexpected bond with the actor in his final years. The documentary is so amazing that it renders Nosferatu in Venice something of an afterthought, but the main attraction is worth watching. Here you have Christopher Plummer as a Van Helsing type (hamming it up on purpose, as the doc makes clear; Kinski left him no choice), Donald Pleasence, misty Venice location shots, and an appropriately haunted-looking Kinski, donning the familiar rodent-like fangs of Herzog’s film (but refusing to wear the rest of the makeup). There’s much which is muddy and confused, but against all odds, the film has atmosphere to spare. It’s even Jean Rollin-esque at times.

Shout Factory seems to have adjusted their release model for older (non-Hammer) B-movies, Roger Corman ones in particular, to limited edition releases, increasing their desirability by default. This extends to their new Blu-ray of AIP’s The Brain Eaters (1958), a 61-minute B-movie that would work much better if presented as it was intended: one half of a double feature (it was paired with The Spider, aka Earth vs. the Spider, in many markets). An alien rocket is discovered too late, for an invasion is already underway, the parasitic aliens (which are actually quite adorable) controlling human hosts by latching onto the back of the neck. Its plot bears similarities to Robert A. Heinlein’s 1951 SF novel The Puppet Masters, which prompted Heinlein to sue the film for plagiarism (it was settled out of court; the book ultimately received an official big-screen adaptation in 1994). And really, there’s not much more to say about The Brain Eaters. Most of the scant screen time is taken up with talking; a pre-Star Trek Leonard Nimoy has a bit part; there’s a nifty glowing orb that the human puppets carry around; and I do like the idea that their spacecraft consists of cramped crawlspaces that worm back and forth, adding a nice touch of claustrophobia to an otherwise suspense-free hour (-and one minute). But, obviously, if you’re in the mood for a 50’s AIP SF movie, it is suitable junk food.

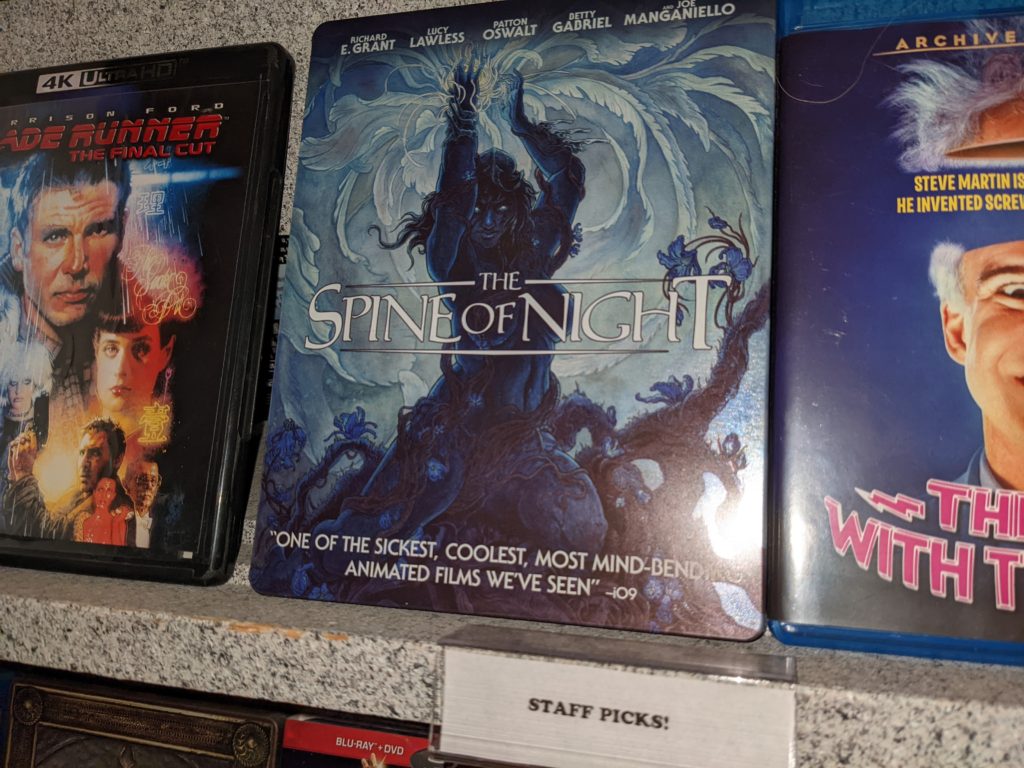

Staff Picks

A few years back, animator Morgan Galen King reached out to me, suggesting I might enjoy his short film “Exordium” (2013). And yes, I did – very much! The film is a psychedelic throwback to the rotoscoped animated films of Ralph Bakshi (The Lord of the Rings and Fire and Ice in particular), as well as Heavy Metal (1981) with its bodies exploding into gooey lumps at the slice of a sword. What I didn’t know from the very brief exchange was that King had embarked upon a feature-length expansion of his concepts, which, after many years of production and countless hours of animation, would become The Spine of Night (2021). Like the aforementioned Bakshi films, King, along with co-director Phil Gelatt (who wrote segments for the Netflix anthology Love, Death & Robots, and directed They Remain), filmed actors with costumes and props in a warehouse before the painstaking animation work began. The end result was worth the effort. It’s an epic, multi-generational tale told by a naked pagan sorceress (voiced by Lucy Lawless) to an ancient warrior known as The Guardian (voiced by Richard E. Grant). She recounts the efforts to control an alien flower called the Bloom which grants cosmic powers. (Patton Oswalt plays one of the characters, the grotesque tyrant of a swamp village.) Pleasingly digressive with an ever-changing cast of characters, and featuring beautiful background paintings, compelling (and very bloody) animation, a thrilling battle in and around an airship, and a memorable creation story partially inspired by the myth-telling in Marcell Jankovics’s animated film Son of the White Mare (1981), this is a film that left me saying, Show me more. Here’s hoping there will be. The film is now available in a steelbook which includes both a 4K UHD and Blu-ray.