Welcome back to Midnight Video, the video store I opened in my basement! Here’s a quick update on new arrivals (just down the stairs; bathroom’s past the first aisle on the left).

Delta Space Mission

New Arrivals

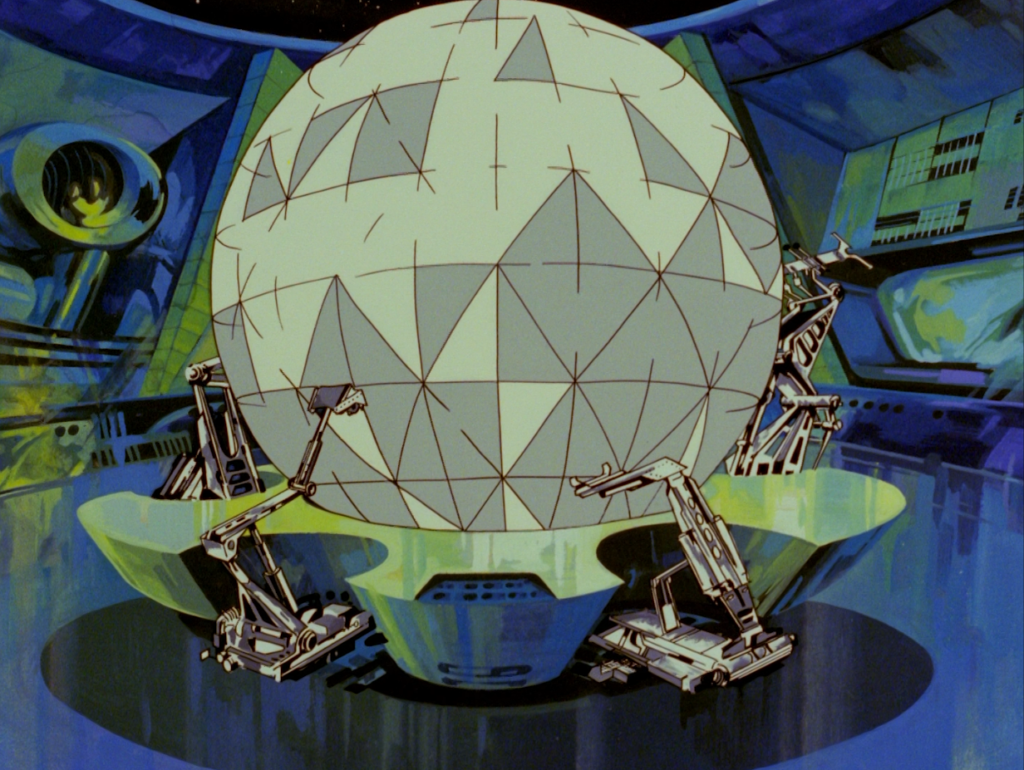

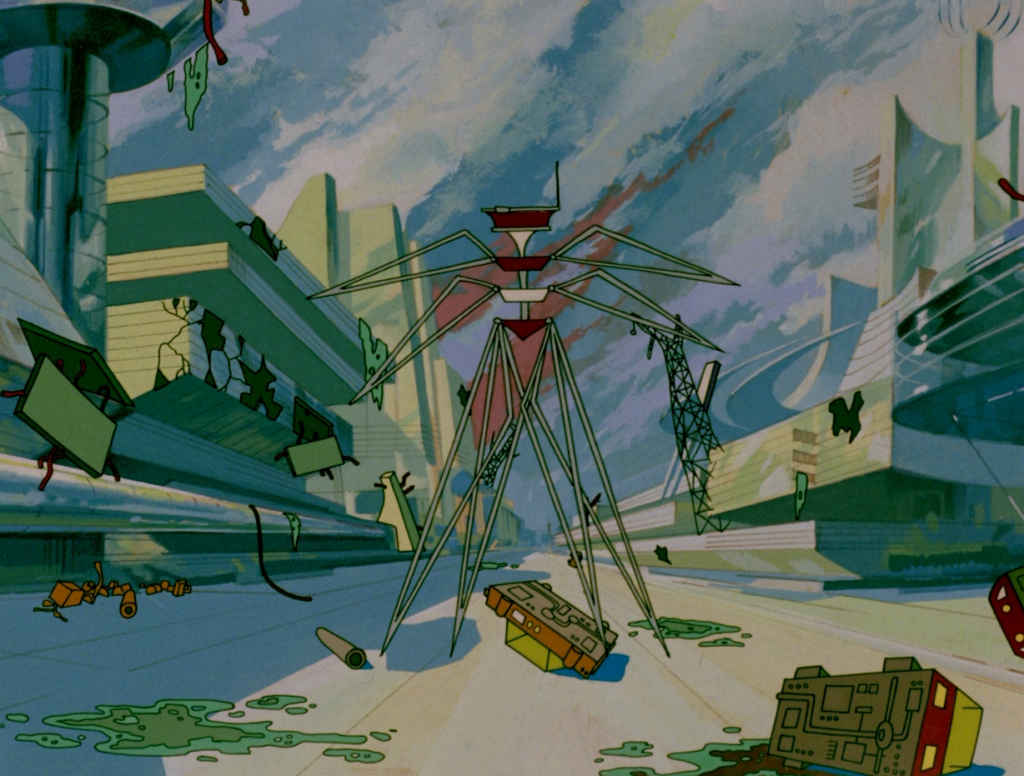

I’ve never been as excited about a new label as I’ve been about Deaf Crocodile, a film restoration and post-production company which is now expanding into Blu-ray releases of international titles as one of the latest partners of Vinegar Syndrome. They’ve already released Jean Louis-Roy’s surreal espionage movie The Unknown Man of Shandigor (1967) starring Daniel Emilfork (of The City of Lost Children fame) and Serge Gainsbourg. They’re also working on delivering new restorations of Aleksandr Ptushko’s Soviet fantasy classics Ilya Muromets (aka The Sword and the Dragon, 1956) and Sampo (aka The Day the Earth Froze, 1959), along with Karen Shakhnazarov’s satire Zerograd (Zero City, 1988). As soon as they announced the Romanian animated science fiction Delta Space Mission (Misiunea Spatiala Delta, 1984), I jumped on it – and I had never heard of the film before. Directed by Mircea Toia and Călin Cazan, this 70 minute feature was actually created on the back of a series of short “Delta Space Mission” films conceived by animator Victor Antonescu for Romania’s Animafilm studio. (Two of these, totaling 14 minutes, are included as extras on the disc.)

A dizzying opening introduces us to a confusing array of characters, previously introduced in the short films, including a pair of space pilots named Dan and Oana, who call to mind Valerian and Laureline from Jean-Claude Mézières and Pierre Christin’s classic French comics of the same name. The majority of these characters prove largely inconsequential. Instead, we spend most of the film’s running time with Alma, a green-skinned alien journalist with frizzy red hair, and her pet “dog,” the frog-like Tin which has stalk-eyes, walks on two legs, and gets into a variety of comic adventures with alternately hostile and unduly affectionate lifeforms. Alma has become the object of infatuation of a supercomputer which subsequently acts out by wreaking havoc, animating rock-creatures, city structures, and a tidal wave that rolls down a metropolitan freeway with grasping hands. Once Alma sets down on a strange planet and becomes separated from Tin, directors Toia and Cazan go full René Laloux – presenting its strange inhabitants with the same xenobiological fascination as Fantastic Planet (1973). Tin is also tormented by an army of miniature shape-changing robots, in a comical game of cat-and-mouse. Star Wars (1977), naturally, proves a big influence as well, notably in a dogfight with ships that look suspiciously like Tie Fighters.

But the style of the film is less easy to pin down. One word that kept springing to mind while watching was “liquid.” Humans and aliens, animals and plants, robots and spaceships – they all seem to swirl about each other like a multicolored liquid light show. When pausing the movie at random to let the dogs out, the frozen image revealed a character’s moving hand rendered by the animator into an abstract shape as though it were melting. The effect is almost subconscious when watching the characters in motion. And while most animated films follow a rigorous series of character models to maintain consistency, there is nothing consistent in the designs of Delta Space Mission, nor in characters or landscapes from scene to scene. The effect is truly dream-like, and it’s all accompanied by a pulsing electronic score by Calin Ioachimescu, like the soundtrack of Forbidden Planet (1956) reinterpreted for an 80’s video game. Indeed, despite the Star Wars influence, space battles on the surface of a space station look instead like a lysergic interpretation of the arcade game Zaxxon. Both my wife and I said almost simultaneously, “Oh, I’ve played this game.” But I still can’t say I’ve seen an animated film like Delta Space Mission before. (It would, however, make an excellent double feature with Laloux’s Moebius-designed Time Masters from 1982.)

Paranoiac

Shout Factory continues to work through the last remaining Hammer titles they’ve licensed, and has just about made Universal’s 2016 Hammer Horror 8-Film Collection Blu-ray set obsolete by fixing questionable aspect ratios and adding considerable supplements. (Granted, it’s a much pricier effort to buy these individually, but that’s the Shout model when it comes to their Hammer line.) One of those upgraded titles, Paranoiac (1963), was recently released with attractive new cover art by Mark Maddox, and the last, the Dr. Syn-based swashbuckler Night Creatures (aka Captain Clegg, 1962), is already on the way. Your mileage may vary, but I consider Paranoiac to be one of the lesser titles in that Hammer subgenre of black-and-white, Les Diaboliques-inspired thrillers. Having not revisited this film in many years, I’d largely forgotten its details, recalling only the rather terrifying-looking mask of the hook-handed fright you can see in the screenshot above. Well, that and the presence of young Oliver Reed, who is always wonderful even when Hammer miscasts him – which is certainly not the case here. He plays another of his hotheaded, internally tormented pleasure-seekers, not all that removed from his brutish role in Joseph Losey’s The Damned (1962). And Oscar-winning cinematographer Freddie Francis directs, which means that the film looks great, with some experimental visual flourishes here and there.

But the plot, in fact, is pretty unmemorable. Simon (Reed) and Eleanor (Janette Scott, now best known for being name-checked in Rocky Horror) are still recovering from the suicide of their brother Tony and the tragic death of their parents. Eleanor is an emotional basket case. The alcoholic Simon, while plotting to take his full inheritance, conspires with his lover, Eleanor’s nurse (Liliane Brousse from Hammer’s Maniac), who isn’t really a nurse after all. Also in the picture is the vaguely sinister Aunt Harriet (Sheila Burrell). Into this house of secrets and conspiracies comes a man (Alexander Davion) claiming to be their brother Tony – but is he really? Eleanor quickly comes to trust him – but is she also falling in incestuous love? And what’s going on in the chapel late at night, where someone is playing an organ, accompanied by an ethereally voiced singer? Oh, that’s where the creepy masked figure with the hook comes in. And it’s also a mite too similar to the midnight frights of that other Jimmy Sangster-scripted production, Taste of Fear (aka Scream of Fear, 1961), which would remain the gold standard for Hammer’s forays into the world of keep-them-guessing psychological thrillers. The old gaslighting plot was also wearing pretty thin by this point, but even Sangster, who could, at his best, be pretty rigorous at setting up some sturdy twists that don’t fall apart when the curtain closes (see, again, Taste of Fear), gives a half-hearted effort here, with little logic given to Eleanor’s behavior, especially after she learns some critical information late in the film. But what may stick is the absolute depraved insanity of the final scene, in which Reed seems to preview his taboo-breaking work with Ken Russell. Is Paranoiac diverting? Sure! Does it make a lick of sense? Not at all!

Midnight Video