The opening credits of this 1972 American International production proudly announce “Ray Milland and ‘Rosey’ Grier as…THE THING WITH TWO HEADS TWO HEADS.” In the interest of promoting racial harmony, it delivers a drive-in parable of an old, wealthy, sickly, and very racist white man (Milland, of Dial M for Murder and many others) whose head is transplanted onto the shoulder of a death row inmate (Grier, of various 70’s TV shows). Alternately, racists and birthers might enjoy the film as an elaborate conspiracy theory detailing how the black man got the white man to vote for Obama in ’08 (through a head transplant onto the black man’s body so’s the white man has no control of his voting arm!). Although perpetually distracted by car chases and surgery scenes, The Thing with TWO HEADS TWO HEADS might be the most cuddly drive-in movie ever made, since Milland and Grier spend most of the film’s running time with their cheeks pressed snugly together. While screaming “Shaddup!” at one another, but still.

Doctor Maxwell Kirshner (Milland) is the most brilliant transplant surgeon in the world. He’ll transplant anything. But he’s dying of terminal chest cancer, and is carted around in a wheelchair in the confines of his mansion, where he lives with a full-time medical staff, mostly attractive young nurses. The film begins just as he’s completed his latest transplanting miracle: he has grafted one gorilla’s head onto the body of another. Once the transplanted head grows accustomed to the body (30 days), the original head is removed. In medical parlance this is known as “squatter’s rights.” After a slapstick chase scene in which the two-headed gorilla (makeup artist Rick Baker) escapes the lab and wreaks havoc in a local grocery store in pursuit of bananas, the final operation is performed, and Dr. Kirshner decides to reveal his strategy to his faithful friend Dr. Desmond (Roger Perry, veteran of a superior AIP product: Count Yorga, Vampire). Milland’s delicately over-emphasized phrases are actually setting up plot points which become kinda sorta important in the film’s abrupt climax. Lest you think he’s just overacting.

Dr. Kirshner needs a new body to sustain his life, but he’s no murderer. He simply needs a donor who has no further use for his entire body. Dr. Desmond drops in on the governor and asks if there are any death row inmates he might be able to procure. The governor is happy to oblige, provided they keep this on the down-low, since technically, legally, you’re not really allowed to donate inmates for dangerous medical experiments. But he has no idea what the doctors really have in mind, or it might have delayed his enthusiastic answer by another thirty seconds at least. Thus, in the local prison, a warden announces a new program for which anyone on death row can volunteer–a transplant operation which they will not survive, but will at least extend their sentence by another thirty days. The situation becomes more urgent as Dr. Kirshner lapses into a plot-convenience coma. Luckily, a volunteer donor arrives at the last possible minute–Jack Moss, who comes with his own soul-music theme song:

Moss, who looks uncannily like Orson Welles, has always protested his innocence of any crime and sees this medical procedure as an opportunity to give his gal back home more time to gather evidence to get him pardoned. But he’s under the impression that the procedure would be more in the realm of donating something less useful, something more hidden and squishy. He’ll learn soon enough. After they unstrap him from the chair, he’s hastily driven over to the mansion, where Dr. Desmond, fully aware that his colleague is the most hideous racist in the entire state, makes a quick decision to go forward with the operation anyway. Kirshner, being in the plot-convenience coma, offers no complaint. Note the superbly executed choreography in this scene where Moss is conducted into a crowded basement lab. The viewer is not spared a second of this extremely important moment.

The operation ensues, in a very long sequence in which Dr. Desmond barks out requests for every surgical instrument and procedure that the writers could hastily locate in a medical encyclopedia. (“Arterial clamp. Suction. Cups. SPONGE. SPONGE! Arterial clamp.”) Tense minutes pass. Quite a lot of them. At last Kirshner’s head has been stitched onto Moss’s body, with the two actors cheek-to-cheek, a neckbrace helpfully disguising the scars, and Milland presumably spooning with Grier behind the prop bed. When Kirshner awakens, he’s thrilled to feel that he already has control over one of the hands. But when he lifts it into view, he does not react well. “Is this some kind of JOKE?” Nevertheless, his reaction is nothing compared to Moss’s surprise:

It’s not long before the panicked Moss, who has greater control over the body while he’s conscious, secures an escape. He takes for his hostage Fred Williams (veteran TV actor Don Marshall), a brilliant young African-American doctor who had come to the facilities to serve under Kirshner, before learning of the less attractive aspects of Kirshner’s otherwise winning personality. Moss hopes to convince Kirshner to perform a reverse surgery; a.k.a. a decapitation. Dr. Williams warns that such a procedure is dangerous, since it could result in the death of both men. But who has time to discuss such matters when the cops are hot on their trail?

Naturally, it’s not long before Dr. Williams and The Thing with Two Heads must ditch their car and steal a motorcycle, joining up with a dirt bike race with the cops still in pursuit. Round and round the course they go, beating not just all their fellow racers but also the police cars, foiled time and time again by the challenges of the course.

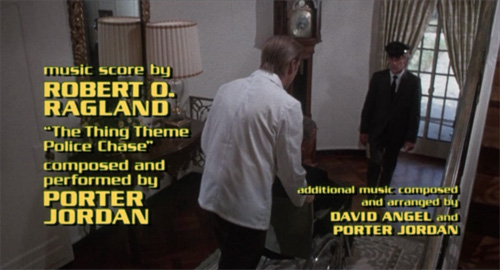

Eventually the chase extends to the broader countryside, with more and more crashes, but for the full effect, you can just play the above clip on a loop for about half an hour. The viewer was, however, fairly warned by the exceedingly specific musical credits in the film’s opening titles:

Yes, you won’t be able to get that catchy “The Thing Theme Police Chase” out of your head, except that I can’t remember it. At last cars stop dropping out of the sky and down ravines and the fugitives escape to Moss’s home, where they can’t even discuss a strategy over dinner without much, much awkwardness.

The governor faces a political disaster: the details have leaked to the press, and also, for some reason, the public is most angry not that an escaped convict has been donated by the state for a medical experiment converting him into a two-headed monster, but just that he hasn’t been electrocuted yet. So the chase intensifies, while Dr. Williams decides that sure, he’ll help Moss cut Kirshner’s head off the body, because he’s decided Moss is an innocent man, and geez, Kirshner’s a real ass. But while they’re raiding a facility for medical supplies, Kirshner regains control of the body. In case you’re wondering about the logistics of a transplanted head regaining control of its body, apparently it involves a lot of face-smooshing:

Kirshner is now ready to remove Moss’s head, even though thirty days haven’t passed, but all that laborious exposition had to serve some purpose. Although we have spent much of the film with actor Grier running around with an open-mouthed Ray Milland dummy head taped to his shoulder–roughly as convincing as the fake Zaphod Beeblebrox head in the 1981 Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy–now Milland gets to run around in a fat suit with a Grier head taped to his shoulder. Somehow this makes him look even more like a two-headed Orson Welles. With Moss still out cold, Kirshner begins the operation. It’s up to Dr. Williams to save the day, interrupting Kirshner, and performing a blessedly off-camera surgery that leaves the doctor’s head lying forlornly on the table while Moss can return to his normal life. This sudden denouement ends with a chorus of “Oh Happy Day” sung by our black actors while the ending credits roll.

So I guess racial harmony wasn’t really achieved after all; at least, not without leaving the racist a bodiless head, whose only hope is a sequel. The possibilities are riper than the long-running Frankenstein series with Peter Cushing…perhaps we could have Ray Milland’s head attached to the body of a Mexican migrant worker (“they should build a FENCE!”), or the hump of a camel (“I CAN’T STAND Arabs!”), or a set of Encyclopedias Britannica (“you’re nothing but another Harvard ELITIST!”)? Alas, it was not to be.