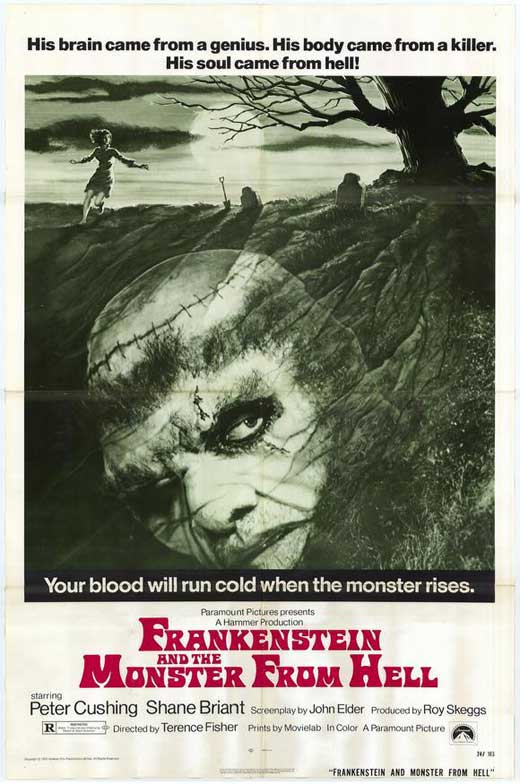

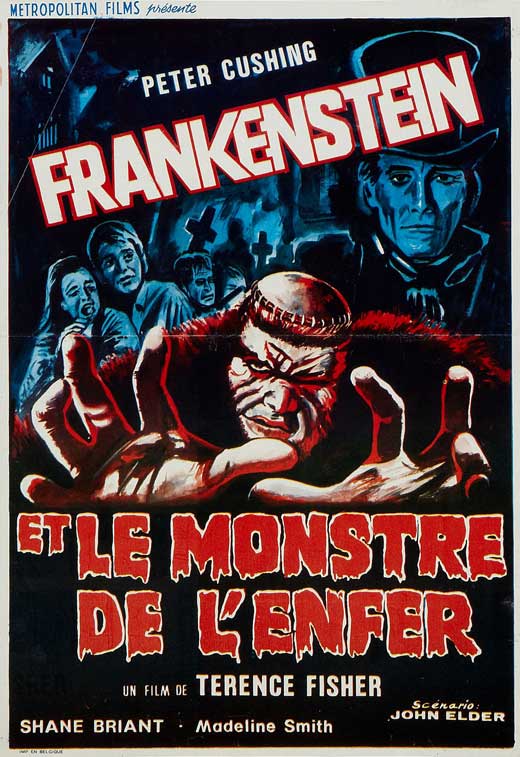

Each time I watch Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974) – the final entry in Hammer’s Frankenstein films – there’s a twitching part of me that wants to leap out and declare this my favorite of the series. What keeps my enthusiasm restrained is the memory of the bigger budgeted, more handsomely mounted, and intellectually provocative entries that preceded it. The films, all but one featuring Peter Cushing as the Baron, and most of them directed by Hammer’s master of the Gothic, Terence Fisher, make for a first-rate franchise. Surely this is nothing much more than a classy, satisfying note on which to end the series, a production whose primarily goal is to atone for the sins of Jimmy Sangster’s poorly-received reboot The Horror of Frankenstein (1970)? Monster from Hell is a small-scale effort, cheaply made during a period in which Hammer struggled to finance their films. The extreme “Neanderthal” monster makeup is a borderline-goofy choice, though nowhere near as unconvincing and off-putting as that featured in The Evil of Frankenstein (1964). Nothing very much happens in the story, which is simplicity itself. Yet almost everything about Monster from Hell grabs me. The title might be over-the-top, but Fisher and his cast take a more understated path. The gimmicks are stripped away, the familiar formula cut down to the bone, and we are left with a stark character study of Baron Victor Frankenstein in his autumn years, still slopping gore onto his fire-scarred hands and viewing his fellow humans strictly as organ donors.

Shane Briant as Frankenstein’s brilliant protégé, Simon.

Shane Briant was one of the studio’s choices to carry the torch of Hammer Horror Star in the 70’s. His dashing good looks and ease at playing arrogant, beautiful monsters carried him through the unnerving, off-brand shocker Straight on Till Morning (1972), as well as Demons of the Mind (1972) and Captain Kronos: Vampire Hunter (1974); no surprise that he was also cast as Dorian Gray in a 1973 TV movie. Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell both plays into and subverts Briant’s established persona. As the film opens, his character, Simon, is being arrested while trying to assemble a Frankenstein monster of his own, to which he casually confesses in the exact same manner as the Baron in previous films. He proudly doesn’t hold to the moral standards of society, and knows that they can barely grasp the significance of his work, so why bother hiding it from them? He’s never met the Baron, but when the sentencing judge compares him to Frankenstein, he’s quick to admit that he’s a big fan: “I have all his books.” He’s thrown into an asylum for the criminally insane, where his self-confidence momentarily causes the director (John Stratton) to mistake him for a legitimate doctor and not one of his inmates. Only a blast from a hose – so strong that it breaks his skin – finally brings him low, while the gibbering inmates gather round. He’s rescued by Frankenstein (Cushing) himself, posing as the asylum doctor. When Simon identifies the Baron at once and professes his admiration and willingness to keep his secret, he’s soon accepted as his assistant, to work alongside Sarah (Madeline Smith), a patient driven mute by trauma. Frankenstein isn’t terribly reluctant to accept the help, perhaps because he’s been through this pattern before, as we’ve seen in previous films. He often has someone at his side who recognizes the importance of his studies, and he likes having his considerable ego nursed. It isn’t long before Simon discovers that Frankenstein is continuing his experiments, using the asylum’s prisoners as a steady supply chain for his new creature (played by Darth Vader himself, David Prowse).

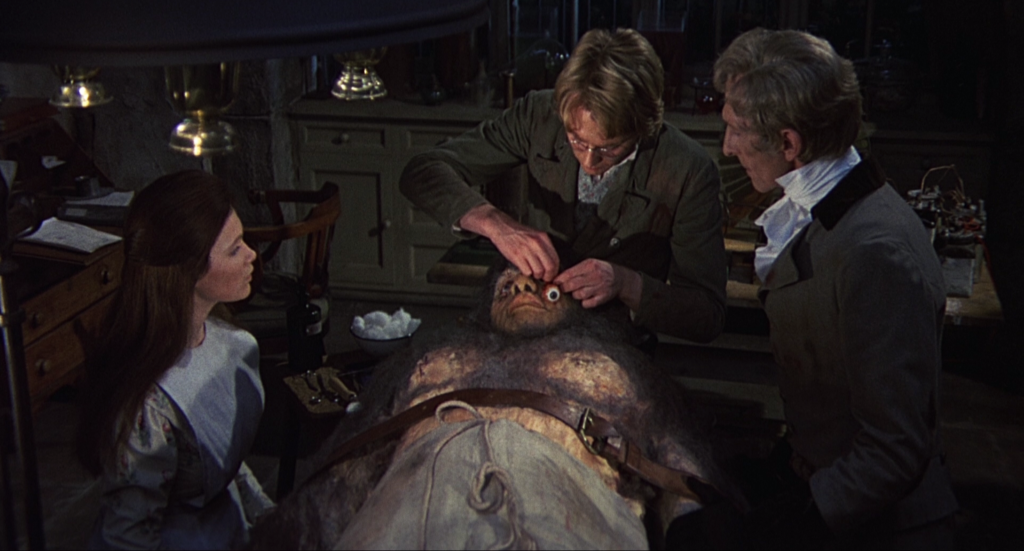

Sarah (Madeline Smith), Frankenstein (Peter Cushing), and Simon at work on the monster.

But as the story progresses toward its inevitable, history-repeating conclusion, we can see the pangs of conscience forming cracks in Simon’s porcelain exterior. He doesn’t see much of a problem with using the body of a patient who had “regressed” to a primitive state (our ape-man monster for this outing), but as he listens to the Baron’s justifications for preying upon the inmates, we see his doubts. First he discovers that an inmate who’s taken his own life was subtly coerced into doing so by Frankenstein. Then he learns that Frankenstein actually plans to mate his creation with Sarah. To make matters worse, Frankenstein possesses the knowledge that Sarah’s lack of speech isn’t biological, but psychosomatic – triggered by her father’s attempt to rape her. Any shock could bring her speech back, Frankenstein casually declares, and as though he’s found the perfect opportunity for that shock, states that in mating with the monster “her real function as a woman could be fulfilled.” Finally Simon’s idol-worship of Frankenstein shatters. He goes to Sarah to protect her from a monster – Frankenstein himself. The grisly climax, and Simon’s visible horror that the Baron will once again pick up the (literal) pieces and resume work again in the morning, seems to act as Fisher’s grim and sardonic comment on the series’ “hero” as a whole. No, the fire-scarred surgeon does not perish at the film’s end. He moves on, undying – that is the legacy of Hammer’s Frankenstein.

David Prowse as the Monster from Hell.

There’s a quaint-looking model used for the asylum’s exterior, and the monster makeup often looks too much like a rubber shell with an actor hidden underneath, but on the whole Fisher makes the most of his very limited budget. The gore effects are excellent, although, unfortunately, the new Shout Factory Blu-ray presents the censored theatrical print, losing an important moment in which Cushing clamps an artery with his teeth (since his hands are so ineffective).* Fisher even keeps Smith to a strictly demure wardrobe, despite the fact that the Vampire Lovers and Up Pompeii actress was a sex symbol, having even become a Bond girl in Live and Let Die (1973); considering the revelations about her character late in the film, the lack of typical sexploitation is welcome. So yes, this might, actually, be my favorite Hammer Frankenstein – but I’ve always liked a strong ending, and this distinguished series couldn’t have gone out any better.

*On the Shout Blu-ray: it ports over an old commentary track and adds a new one, but the lack of effort put into it is pretty surprising considering that the company has been doing a superb job lately on creating definitive – or close-to-definitive – presentations of Hammer titles, most recently Kiss of the Vampire and The Phantom of the Opera. The deleted shots should have been included, and this film certainly deserves more than a shrug.