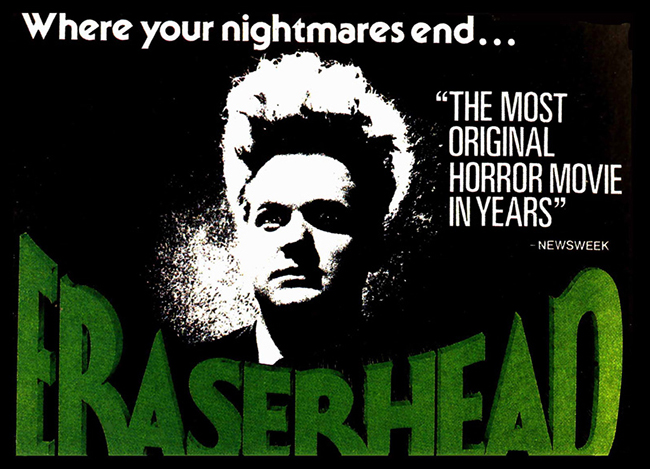

2021 is the 10th anniversary of Midnight Only. To mark the occasion, this imaginary, rat-infested, leaky-roofed theater is raising the curtain on historically important midnight movies.

The following was originally written for this site on July 21, 2015.

One of the most important images in David Lynch’s debut feature Eraserhead (1977) comes toward the end of a surreal montage, meant to establish a chain of strange motifs and to cold-immerse the viewer into the nightmare world of the film. It is Henry Spencer (Jack Nance) silently screaming in terror. Silently – inwardly, like a man collapsing in on himself, as the image of a squishy parasite-like fetus-thing floats superimposed out of his mouth. I can’t define what that thing is because Lynch likes to keep his nightmares indefinable. The most important thing is that it prods like a hot poker at a certain part of your brain – because your subconscious identifies it, and recoils. No matter how weird Eraserhead gets, we will always understand what that silent scream is about, and what Henry is suffering – even if we can’t put it into words ourselves. Lynch has never made a genre horror film, and yet he’s so well versed in the mode of nightmare that some of his pictures rank with the most frightening and unsettling ever made. It’s said that Kubrick loved Eraserhead so much that he screened it for the crew of The Shining (1980) so they could channel its bad vibes. Notably, The Shining also features a silent scream, Edvard Munch-style – this from a young psychic boy on a Big Wheel, with nothing to protect him from the great malevolent ether at the Overlook Hotel. Replacing his scream, and Henry Spencer’s, is the deafening noise of the soundtrack. (Like Lynch, Kubrick loved his sound design.) The environments of both Eraserhead and The Shining are paralyzing. The dread is incapacitating to its characters.

Henry Spencer (Jack Nance) meets the parents (Jeanne Bates, Allen Joseph) of Mary (Charlotte Stewart).

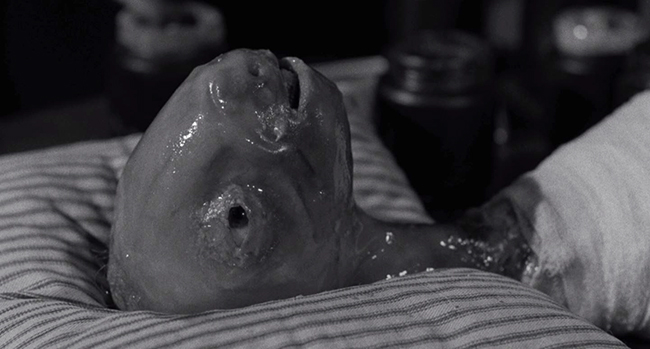

Of course, both films are also impeccably shot. It’s astonishing to see the quantum leap in style between Lynch’s cruder early films and his first full-length feature, though they all have clearly emerged from the same disturbed imagination. The perfectly composed images are rendered in lush black-and-white by cinematographers Herb Caldwell and Frederick Elmes. Eraserhead looks like it was filmed during the Golden Age of Hollywood – so its grotesque sights are like a viral infection, mutating and deforming the landscape. In the process, the kitchen-sink drama becomes a punk-art parody. A musical number is marred by hideous facial prosthetics and more squishy umbilical-like things dropping out of the rafters. There is a certain connection here with the Hollywood-parodying, taboo-breaking underground films of the Kuchar brothers and John Waters. No wonder the film became a hit as a midnight movie. And like seminal midnight movie El Topo (1970), the narrative is a symbolic one, and a loose framework on which can be applied a series of bizarre and sometimes shocking abstractions – perfect for late-night viewing. (Lynch has called it “a nighttime film.”) Everyman clock-puncher Henry, with a vertical coiffure and a pocket protector, is contacted by his estranged girlfriend Mary (Charlotte Stewart – who, like Nance, would later be featured in Twin Peaks). Over the most awkward meet-the-parents dinner in cinema history, Henry learns that Mary has given birth to a premature baby – though she says, “They’re not even sure that it is a baby.” Henry is given a stern lecture to wed Mary and take responsibility for the child. “You’ll be in very bad trouble if you don’t cooperate,” Mary’s mother says. The film then reveals the infant, a skinless, moist, bug-eyed, mewling thing, and whose tiny body is hidden in bandages. Eraserhead finds its disturbing rhythm in sequences set largely in Henry’s claustrophobic apartment, of harrowing child care, domestic dissolution, dreams and nightmares.

The baby.

Among the film’s many strange sights is the Man in the Planet, who seems to act as a kind of mute Chorus, bookending the film as he looks out his window toward the universe, sporting a hideous complexion, and pulling a huge lever like a laborer in Metropolis (1927). Across the cramped hallway from Henry’s apartment lives a sexy neighbor (Judith Roberts, Stardust Memories), who seduces Henry after Mary has fled back to her parents’ house. As the two embrace, they sink down into what resembles a smoking witch’s cauldron. The radiator occasionally lights up from within, revealing a stage framed by coils and encircled by footlights. Henry eventually has a vision of a singer with huge chipmunk cheeks, who serenades him from the radiator with the film’s original song, “In Heaven.” She seems to represent unobtainable hope and comfort, despite the alarming makeup. In what plays like a film-within-a-film, Henry dreams of being decapitated on her little stage, sprouting the head of his baby. His severed head is then found by a boy on the street, who delivers it to a factory where it’s used for the manufacture of pencil erasers. (The most iconic image of the film is Jack Nance framed by a cloud of eraser dust, white motes swirling about him against a black background like the film’s recurring starfield imagery.) Throughout, the soundtrack is persistent, offering little opportunity for peace – just like living in an apartment in the city. A roar of airplane engines. The whistle and rumble of a train. Henry tries to drown it all out by playing Fats Waller organ music, which nonetheless sounds like someone else is having a good time, long ago and far away.

Final embrace with the Lady in the Radiator (Laurel Near).

There are connections to Lynch’s films past and future. The idea of a suffering male protagonist seeking motherly comfort and reassurance against a frighteningly adult world almost makes this feel like a sequel to Lynch’s 34-minute film “The Grandmother” (1970), along with the recurring images of roots and piles of soil (in the short, a young bed-wetter with abusive parents grows his ideal grandmother from a seed planted in an empty bed). The zig-zag pattern in the lobby of Henry’s building reappears in Twin Peaks. The stage inside the radiator is like Henry’s own Club Silencio, of Mulholland Drive (2001). Light bulbs flicker demonically and the shadows are always an all-consuming black. Lynch’s first feature film is from an artist fully-formed. He writes and films straight from his subconscious, with little filter. But there is a clear theme of domestic implosion which emerges from the delirium of Eraserhead. Lynch’s daughter, director Jennifer Lynch (Boxing Helena, Surveillance), has pointed out that she was born with club feet and put in a cast, a natural inspiration for the movie’s convincing moments of stressful child care (and bandages). And Lynch went through a divorce during the film’s production, which makes it tempting to read into the film’s scenes with the frustrated Henry and Mary. But Lynch has pointed out that the film is inspired by innumerable things, and should be left to one’s personal interpretation. There is also plenty of pitch-black humor which shouldn’t be overlooked – especially during the dinner with Mary’s parents. After the catatonic grandmother is left in the kitchen with a cigarette, miniature chickens are brought out on a platter. Henry is asked to slice the first chicken, which perplexes him: the long, curved carving knife dwarfs the meal. Then the chicken legs begin to twitch, and blood pours and pools from between them, an image of miscarriage or abortion. Mary’s mom begins to have a seizure – or an orgasm. Mary eventually bursts out crying, and her mother goes to speak to her in the opposite room. Father stares for a very long time at Henry, grinning in silence. Then he says brightly, “Well, Henry, what do you know?”