By the time this episode aired, The Twilight Zone had already become legendary for its outlandishness. Previously, science fiction, fantasy, and horror were seen as kids’ stuff, and though Rod Serling had already established himself as a screenwriter of note, a half-hour anthology series devoted exclusively to the fantastic was no easy pitch to the networks. Thankfully, CBS picked up the pilot, “Where is Everybody?”, and by the end of the show’s first season, The Twilight Zone was a sensation with a devoted fan base. Season Two launched in late September of 1960 with a new musical theme – the one we best know today, and whistle whenever something odd occurs – and an opening credits sequence (a black line cuts across the screen to form an artificial horizon, and a sun sets against it) that was slightly modified from what was used in the latter episodes of Season One. Serling’s opening-credits narration is truncated, and he speaks more urgently, almost sounding panicked as he warns you about that signpost up ahead. All of this quickly acclimates the viewer to another 25-minute trip into the realm of the bizarre and eerie. What viewers on this November 18 were not expecting was “Nick of Time,” an episode that would play off their expectations of the series, and suddenly turn the mirror upon themselves. Speaking of mirror-reveals, “Eye of the Beholder” had aired the week before, one of the series’ key triumphs, a high-concept science fiction tale with fantastic makeup by William Tuttle, executed with perfection on the small screen. But for “Nick of Time,” writer Richard Matheson, in his first contribution to Season Two, focuses not upon the otherworldly but – almost uncomfortably – upon our own frailties as human beings. The supernatural is merely suggested and never proven, but the actions of its central characters can’t be denied.

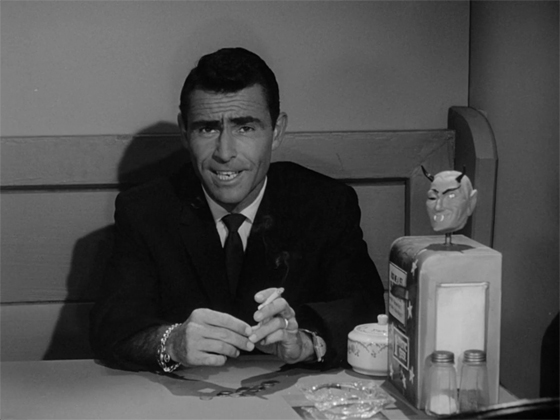

Pat and Don Carter (Patricia Breslin and William Shatner) discover the "Mystic Seer" in the Busy Bee Cafe.

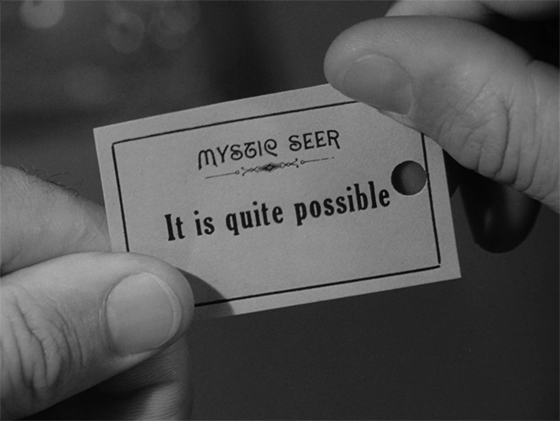

The setup is typical Twilight Zone economic simplicity. We meet two newlyweds deeply in love with one another, Don S. Carter (a very young William Shatner) and Pat Carter (Patricia Breslin, who would soon appear in William Castle’s Homicidal). It would take a second viewing to realize the opening shot is symbolic of the episode’s central theme: they are introduced as passengers, not drivers, riding in their own car as it’s being towed to the local mechanic. They’ve just broken down in a town called Ridgeview, somewhere in Ohio. (Shades of the classic episode “Walking Distance” – if your car breaks in the middle of nowhere, you’re likely to find yourself in the Twilight Zone.) With four hours to kill, Don and Pat head off to the Busy Bee Cafe for lunch and some slow-dancing to the jukebox. At their booth, they’re charmed by the presence of the “Mystic Seer” napkin-holder, with one of those little winking devil-heads suspended above it; drop a penny in it and have your fortune told, provided you keep your question to the “yes/no” variety. Don asks it if anything exciting happens in this small town: “It is quite possible,” the napkin-holder says. He asks if he’s going to be promoted: “It has been decided in your favor,” the napkin-holder says. On a whim, he decides to phone the office. Pat looks worried, and we see her touching her husband’s good luck charms that have been left on the table – a rabbit’s foot and a four-leaf clover. She had the same worried expression when he deposited his second penny. The waters are apparently troubled.

The Mystic Seer predicts...vaguely.

Of course, this being The Twilight Zone, the phone call reveals that he has, in fact, received the promotion he was asking for. He now regards the napkin-holder and its devil’s wink with a new kind of curiosity. More pennies are deposited. “Is it really going to be four hours before we get out of here?” “You may never know,” the napkin-holder says. “You mean something will keep us from knowing, something will happen to us?” he asks. “If you move soon,” the napkin-holder says. “You mean if we’re not supposed to move, we’re supposed to stay here?” “That makes a good deal of sense,” the napkin-holder says. Soon he’s got these vague answers locked down: they can’t leave before 3pm or something terrible will happen to them. Ominous music plays on the soundtrack and Don looks worried: that’s all that matters. We know the little devil must be right. Never mind that it’s answers are no better, and no random, than those you’d receive from a Magic 8-Ball. Pat is skeptical, and it’s a chore for Don to find things for them to do before 3:00 rolls around (needless to say, dessert is ordered). She can’t wait until 3 – she becomes impatient and annoyed. They leave a few minutes before, and, in crossing the street, are almost struck by a car. It’s not very long before Don is dragging his downcast wife back to the Mystic Seer. They just need to wait until those two old women get out of their booth, because even though there are other napkin-holders, other Mystic Seers, this one, Don is convinced, is special. Pat pleads with him, but he has become obsessed – like the gambling-addicted Everett Sloane in Season One’s “The Fever.” She has obviously seen similar behavior in Don before, or she wouldn’t have eyed those good luck charms so nervously. And as penny after penny is inserted into the machine, the cards keep giving unimpressive responses. At one point he explains to his wife that you can’t just expect the cards to call them by name.

As Don and Pat leave, another couple takes their place - further toward the end of their rope.

But why not? According to Rod, they’re on “the outskirts of the Twilight Zone,” after all. The truth is that Matheson is making a choice. “Nick of Time,” like the little winking devil, never commits to an answer. We never learn if anything supernatural has occurred. Don argues with his wife that the Seer told them something bad would happen before 3, and the car almost hit them when they left before 3, so therefore…but she responds softly, “Don, you said 3:00, not the machine. You decided to sit in here as long as we did. You.” Explicitly, the episode is about free will. In the final scene, we get the twist that truly makes this a Twilight Zone installment: as Don and Pat leave, having finally decided to seize control of their own lives, make their own choices, and forget all about little mysterious napkin-holders, another couple steps through the door and sits down at the booth, looking almost withered, their life-energy drained by the penny-machine. “Do you think we might leave Ridgeview today?…Is there any way out, any way at all?” We see what Don and Pat might have become, a few days in the future: self-imposed prisoners who’ve surrendered all their freedoms. A Philosophy class could pair this episode with Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979) for the shared message of “You’ve got to think for yourselves.” And, sure, the fact that the supernatural presence at work is unproven and purely theoretical lends itself to a critique of religion. But indisputably the episode is a fable representing a metaphysical concept, the importance of grabbing hold of the reins, determining your own path. By outlining a worst-case scenario, we can be alerted to those inclinations within ourselves that lead us to surrendering our freedom of choice. Serling had previously shown us the monsters within ourselves with “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street,” but in the final reveal, he delivered the aliens and the flying saucer. Matheson strips his own tale down further: we don’t need extraterrestrial intervention to become subjugated; it only takes our own natural tendency to become helpless passengers.

And – of note – Shatner is fantastic.