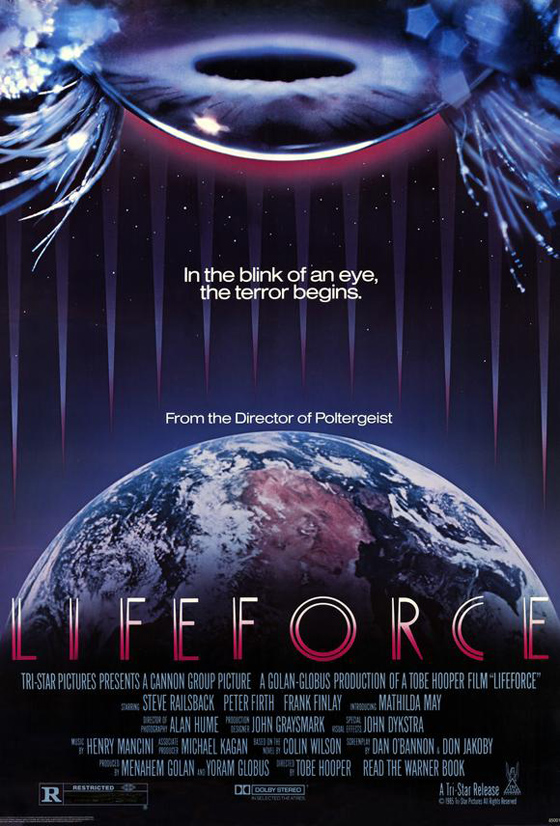

Earlier this year Chicago’s Music Box Theatre hosted the “70mm Festival,” projecting in gorgeous 70mm prints of Vertigo (1958), West Side Story (1961), Lord Jim (1965), Playtime (1967), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968), Hamlet (1996), The Master (2012), and, of all things, Tobe Hooper’s Lifeforce (1985), crashing the party with a sword for slaying topless space vampires. To me, that’s a well-rounded lineup: a Hitchcock, a Kubrick, a musical, a children’s matinee, a Jacques Tati classic, a couple of modern films, and a Golan Globus epic under their notorious “Cannon Group” banner, the same company that brought us Hercules (1983). I first watched Lifeforce as a teenager, perhaps expecting it would be another low-budget 80’s Alien rip-off, like so many of those VHS tapes in that section of the store. I certainly wasn’t expecting an overambitious spectacle with plentiful (and often first-rate) special effects, bizarre makeup, copious nudity, gore, Captain Picard, and all of London descending into rampaging madness. It was as though I were the film’s protagonist, and that VHS tape were the vampire seductress reading my post-pubescent mind and delivering all the R-rated monster movie mayhem I wanted. But here’s the thing: I took the film’s themes very seriously. I drew a Lifeforce comic book and wrote a short story inspired by it. To my young, developing imagination, Lifeforce wasn’t just a big-budget exploitation movie. When Steve Railsback’s Texan astronaut expresses bafflement that he should be so drawn to this soul-sucking alien in her umbrella-shaped spaceship, I was sympathetic, because of my own confused longings and frustrations: I was just as helpless in the presence of girls, after all. I’m much older now, and it’s easier to see Lifeforce for the wondrous trash that it is, just as it’s clearer to me that the film’s ideal audience is teenage boys. They are the only ones who could possibly take this seriously.

A space shuttle crew uncovers a spaceship hidden inside the tail of Halley's comet.

I wasn’t surprised, revisiting Lifeforce on the new deluxe Blu-Ray from Shout! Factory’s horror line, to find that the film was just as wild as I remembered it. Given all the crazed, disparate elements it tries to fold into a single plot, how could it fail to live up to my memories? What continues to fascinate me is that a film of this nature has this particular pedigree. Tobe Hooper had a tremendous mainstream hit with his Spielberg-produced Poltergeist (1982), but signed up with Cannon for Lifeforce, then, in 1986, both a poorly-received remake of Invaders from Mars (again: as an undiscriminating youth, I liked that movie), and an obligatory return to the property that made him famous, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2. That poorly-received trilogy for Golan Globus seemed to permanently distance his name from Hollywood’s A-list. Still, with Lifeforce he had some sophisticated toys to play with, including special effects by John Dykstra (Star Wars), a cast with some pleasingly recognizable faces, a score by Henry Mancini of The Pink Panther and Breakfast at Tiffany’s fame, and a script co-authored by Alien‘s Dan O’Bannon. In other words, Lifeforce is a one-of-a-kind film, with a slick veneer and some real talent in service to a silly story that’s unabashedly lowbrow – so no wonder that its stock has risen in recent years, to the extent of its revival bookings and now this extras-loaded Blu-Ray.

An autopsy is interrupted when one of the vampires' victims proves he has some "lifeforce" left.

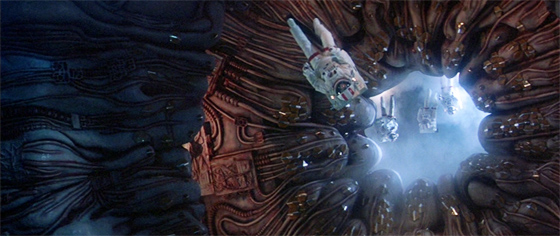

The key ingredient to the film’s particular sensibilities might lie with the screenwriters. Don Jakoby would later pen Arachnophobia (1990) and John Carpenter’s Vampires (1998). O’Bannon will always be associated with Alien, but his particular sense of humor and outré taste might be better represented by the horror-comedy The Return of the Living Dead, which he directed and which was released the same year as Lifeforce. They were tasked with adapting the Colin Wilson novel The Space Vampires, but they borrow little more than Wilson’s basic concept. Despite what I thought in my adolescence, Lifeforce does not take itself very seriously. Though the dialogue is delivered straight-faced, and, in the case of Railsback, dialed up as much as possible (he was best known for his convincing performance as Charles Manson in 1976’s Helter Skelter), this is a film which knows that it’s essentially about naked, body-hopping space vampires who turn people into zombies. The film opens, rather breathlessly, aboard the space shuttle Churchill, populated with a joint British and American crew and in rendezvous with Halley’s comet. Within the first few minutes of the film, they’re already leaving the hatch and floating into the long alien craft they’ve uncovered drifting in the comet’s tail. The ship’s inside reminds of H.R. Giger’s designs for Alien, so we’re in comfortable, if very derivative, territory. Within they discover the dried-up bodies of bat-creatures, along with transparent, coffin-like vessels containing the bodies of naked – and beautiful – humanoids. They take three for further study, two men and a woman, but some unspecified disaster occurs, and it’s a Churchill with a scorched interior that’s intercepted as it drifts toward Earth, with the aliens – dead or slumbering – the only things left untouched by fire. Before she can be autopsied, the female (a gorgeous Mathilda May) comes to life, seduces a lab assistant, and drains his body of its “lifeforce,” leaving only a dessicated husk. This leaves the dignified Dr. Fallada (Frank Finlay, The Three Musketeers) to declare, “A naked girl’s not going to get out of this complex.” A few minutes later and that naked girl’s shattering windows with her mind and strutting out of the building across broken glass.

Astronaut Tom Carlsen (Steve Railsback) interrogates the spirit of the space vampiress inhabiting the body of Dr. Armstrong (Patrick Stewart).

By the time Colonel Caine (Peter Firth, Tess) arrives to seize control of the situation, the alien has left multiple dried-up bodies that violently explode into dust, and, to cover her tracks, has hidden her original body and deposited her consciousness inside another person. Or, as Caine ominously states: “Now she has clothes.” The male aliens also awaken, but are blown to pieces by some security guards who are awfully quick to resort to grenades. A lead arrives in the form of Churchill‘s only human survivor, Col. Tom Carlsen (Railsback), who left the shuttle in an escape pod after the vampires drained his crew and he set fire to the cargo in retaliation. They quickly learn that Carlsen has a psychic connection with the female alien, the result of her lending him some of her own lifeforce. With this talent, he’s able to lead them to her latest hiding place, an asylum for the criminally insane led by the serene-faced Dr. Armstrong (Patrick Stewart), whom Carlsen fingers as the vampire. All this culminates in a scene set in a helicopter, in which blood streams out of Stewart’s face to form the hovering shape of the vampiress, who calls Carlsen’s name before spilling back into a red pool on the floor. Having lost their prey, they return to London, only to find that the vampires’ plague has spread, creating thousands of homicidal zombies running through the streets while the alien craft, having finally reached the Earth, beams up captured souls via a bright blue ray. While Carlsen follows his destiny to join his body with the girl’s – for we’ve by now learned that she’s the ideal physical representation of his feminine side, or something-or-other – Caine takes Fallada’s advice that the creatures can only be slain by staking them: not in the heart, but just a few inches below it, through the center of the lifeforce. He takes up a sword and charges through downtown London, which now looks like a Thriller video, killing zombies and bat-creatures where he may.

The finale has some nifty stop-motion animation for the alien bat-monster.

Inspiration for this finale seems to be drawn from Quatermass and the Pit (1967), the third and best of Hammer’s Quatermass cycle. The naked vampiress also recalls Hammer’s erotic Karnstein trilogy (The Vampire Lovers, Lust for a Vampire, and Twins of Evil), and other similar films from that period. Carlsen’s struggle against the life-draining aliens aboard the space shuttle is equal parts Planet of the Vampires (1965) and Queen of Blood (1966). Surely Hooper, O’Bannon, and Jakoby were conscious of all these influences, even as they mixed them into a delirious, Ken Russell-style spectacle. To the film’s credit, it avoids contemporary trappings, and is now dated only by some of its effects, in particular the awkwardness of the mechanical puppets, though these hand-crafted creations from the pre-CG age also add to the film’s goofy charm. In particular, one brief sequence involving stop-motion animation – as one of the male aliens reveals his true, bat-like form – is bound to be please genre fans. Lifeforce was largely derided upon its release, but in hindsight it’s a delightful rarity, a kind of live action Heavy Metal, an explosion of an adolescent Id, more undiluted, and given far more money and talent, than these sorts of efforts are usually allowed.