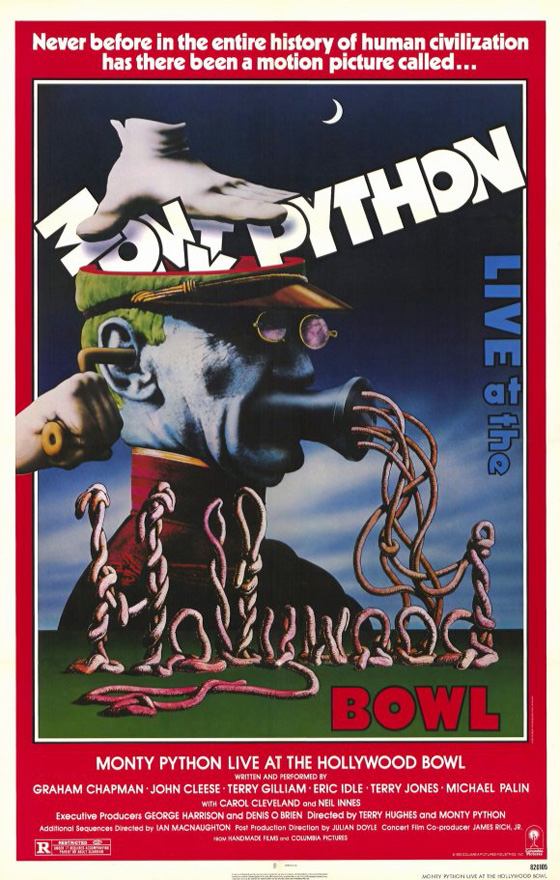

“Welcome to the Ronald Reagan Memorial Bowl!” For four nights during the month of September 1980, Monty Python held court at the legendary Hollywood Bowl to an audience of about 8,000 per show. “[It] tickled all of us,” Michael Palin wrote in The Pythons Autobiography, “because we were all brought up on LPs of people ‘Live at the Hollywood Bowl,’ whether it was Sinatra or Errol Garner or the big bands that played the stage there. And we said, ‘Yeah, okay, we’ll have a go.'” The troupe had performed live sporadically throughout the 70’s, and released comedy albums from two of their shows, Live at Drury Lane (1974) and Live at City Center (1976), but the 1980 performances would be their last hurrah as a stage act, having already conquered film with two of the greatest comedies of the 70’s, Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) and Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979). Secondary output – that is, anything that wasn’t cinema – was dwindling, but they had just released an album of all-new material, much of it musical, called (with just a hint of sarcasm) Monty Python’s Contractual Obligation Album (1980). So ostensibly they had something to promote, and songs from the album were incorporated into the stage show. The primary draw of performing live in Hollywood, apart from the allure of the venue itself, was simply because they hadn’t conquered the West Coast before. Celebrities hung out backstage, including George Harrison, Mick Jagger, John Belushi, Steve Martin (who hosted a pool party for them), Debbie Harry, Carrie Fisher, Marty Feldman, and Harry Nilsson, who was known to crash Python events, literally (in New York, he fell into the orchestra pit while singing backup on “The Lumberjack Song”). Carol Cleveland, recalling those extraordinary days in Monty Python Live!, claims it was “the pinnacle of Python”; as for John Cleese: “I understood the rock concert thing then, and I enjoyed every minute of it.”

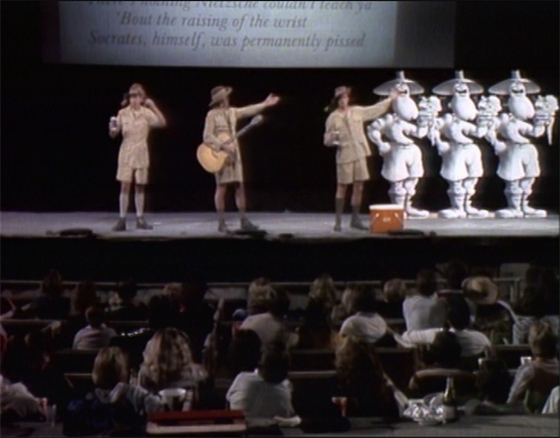

Eric Idle, Neil Innes, and Michael Palin lead the audience in "The Bruces Philosophers Song."

The film – Monty Python Live at the Hollywood Bowl (1982) – was actually an afterthought, released to a handful of theaters a full two years later. Denis O’Brien was the business manager for George Harrison and, with Harrison, the co-founder of HandMade Films (which had a long affiliation with Python, having been formed to finance Life of Brian, and being the production company behind Palin’s The Missionary and A Private Function, Cleese’s Privates on Parade, Terry Gilliam’s Time Bandits, and Eric Idle’s Nuns on the Run). Gilliam, in David Morgan’s Monty Python Speaks!, puts it with his usual bluntness: “Denis was our manager then, he decided to interfere, [and] he completely fucked it up. We had taped the shows, and the money we were guaranteed we didn’t get because Denis squandered it, wasted it, so we actually had to release the tape as a movie here in England to get the money that we’d hoped to get from the stage show; we didn’t want it to go out as a movie.” Cleese and Idle, however, recall that they edited the film together with enthusiasm, and we should all be grateful Live at the Hollywood Bowl exists, as it’s the only filmed document of the Python stage show. Here we see the Pythons performing their greatest hits – “The Lumberjack Song,” “Nudge Nudge,” “Crunchy Frog,” “Silly Walks,” and “Argument Clinic” (but not the “Dead Parrot Sketch”) – along with a couple of older, more obscure bits, and some newer material. Onstage they’re joined by Cleveland and Neil Innes, both of whom could make legitimate claims to being “the Seventh Python,” having appeared on the television series and in the films, as well as being veterans of the tours. Innes sings an old number from his days with the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, “I’m the Urban Spaceman,” originally released as a single in 1968; and he performs “How Sweet to Be an Idiot,” the title track from his first solo album.

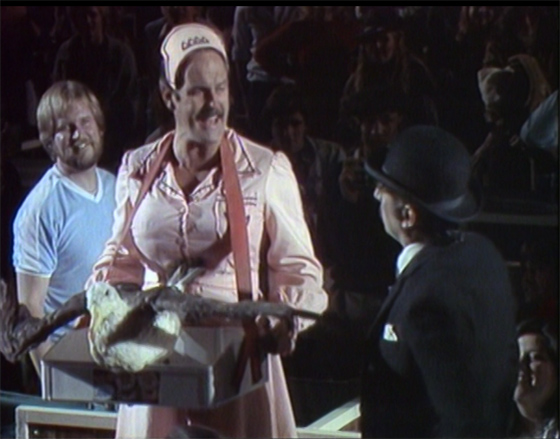

John Cleese sells "Albatross!" during the Intermission, and abuses Terry Jones.

As for the audience, well, as Idle puts it: “All the kids are on drugs and all the adults are on roller skates.” Terry Jones has recalled that you could smell the marijuana smoke as you walked down the aisles, an observation made by Cleese in the film, when, dressed in drag as the Intermission’s albatross vendor, he shouts at one audience member, “You’re not supposed to be smoking that.” During the same sketch, another inescapable fact of their live performance becomes obvious: the crowd has the material memorized. “What flavor is it?” ask several goons, doing their worst British accents a good half-minute before Jones gets to that line (he’s forced to underplay, almost swallowing the words). Since it’s not easy to surprise this audience, the Pythons work extra hard to do just that. Primarily, they goose the material from PG to R. Cleese screams at Jones, “Of course you don’t get fucking wafers with it, you cunt!” A performance of their new, pro-69 song “Sit On My Face” ends with the Pythons mooning the audience, a stunt repeated during 2002’s A Concert for George. During the “Travel Agent” sketch, Cleveland says to Idle, “Have you come to arrange a holiday, or would you like a blowjob?” (What’s even funnier is Palin’s disappointed expression when Cleveland says, “Mr. Bounder, this gentleman is interested in the India Overland and nothing else.”) The “Judges” sketch, in which two camp judges undress to reveal they’re wearing women’s lingerie, contains more risqué wordplay than the televised version: “I gave him three years; he only took ten minutes.” In “Crunchy Frog,” Gilliam’s policeman is so nauseated by the Whizzo Quality Assortment of chocolates that he suddenly vomits (cold beef stew) into his hat – and is forced by the unsympathetic constable (Graham Chapman) to place it back on his head. Other tweaks are milder: during “Nudge Nudge,” Idle is impressed that Jones’ girl is not from Purley, London, but rather from Glendale, California.

Graham Chapman and Terry Gilliam in the "Crunchy Frog" sketch.

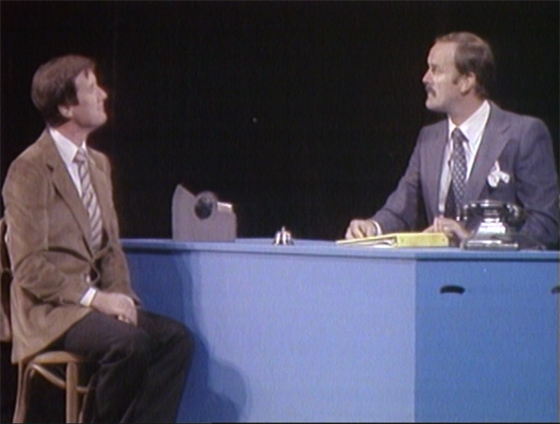

From an historical perspective, it’s particularly valuable to see some of the less-familiar sketches, including an old Chapman solo routine in which he wrestles himself as Colin Bomber Harris vs. Colin Bomber Harris (an astonishing feat of athletic comedy which Chapman would later perform during his college speaking tours). The Pythons also dig up “Custard Pie,” a dissertation on slapstick that Jones and Palin wrote at Oxford, and “Four Yorkshiremen,” a masterpiece of tall-tale one-upsmanship that originates with At Last the 1948 Show (1967) but, thanks to this performance and the version from Monty Python Live at Drury Lane, has become an oft-quoted classic of the Python repertoire. (Nobody really quotes my favorite line in the sketch: “We were evicted from our hole in the ground. We had to go live in a lake.”) “The Last Supper” was written by Cleese and Chapman for Flying Circus but never made the cut; it works perfectly as a rare Cleese/Idle two-man sketch, both of whom have rarely been better in this efficient piece of escalating absurdity. “Now in God’s name tell me what on Earth possessed you to paint this with three Christs in it?” “It works, mate… The fat one balances the two skinny ones.” At the time of the concert and the film’s later release, it would have been an added bonus to see clips from Monty Python’s Fliegender Zirkus, filmed for German television, though the two German episodes are now commonly available. Clips include “Silly Olympics,” “International Philosophy: Germany vs. Greece,” some Gilliam animation involving flashers in love, and “Children’s Hour,” with its tale of Little Red Riding Hood (Cleese), the Big Bad Wolf (a long-haired dachshund), and Buzz Aldrin.

Palin and Cleese square off in "Argument Clinic."

The performers are having such a great time on stage that even Cleese has a sparkle in his eye after performing his silly walks – a sketch for which he’s expressed outright loathing. But “Salvation Fuzz,” aka “The Church Police,” is one of those sketches the Pythons reserved for all undignified corpsing (the other, not present in the film but heard on Drury Lane, is “Election Special”). The sketch was always a loose affair – barely a premise and even sillier than normal. In Hollywood Bowl, Jones, in drag and doing his “Mandy, Mother of Brian” voice, starts cracking up early, followed by Idle, playing the son. When both are required to hop 180-degrees in unison, Jones’ wig flies wide. Idle and Palin, playing one of the Church Police, stiffly move to form a barrier behind which Jones can put his wig back on. From that point on, getting through the sketch is nearly hopeless, though at least the giant Hand of God points at the right criminal this time (it often wouldn’t). That editors Cleese and Idle left this wonderful mess in the film indicates how much affection they had for the laid-back nature of the Hollywood Bowl performances; Cleese claimed that the atmosphere was so relaxed that when he forgot where he was in “Dead Parrot,” he simply asked the audience, “What’s the next line?” They answered, of course. Finally, after the traditional closing performance of “The Lumberjack Song” (performed by Idle rather than Palin) and a wild curtain call (the Pythons chase each other back and forth across the stage), an exhausted “Piss Off” flashes on the screen to the audience that just won’t leave, or stop applauding. Who can blame them? These fans were nearly out of new Python – the gang was just beginning to write what would be their final group effort, The Meaning of Life (1983) – and no one was anxious for the big pink foot to come smashing down, not just yet.