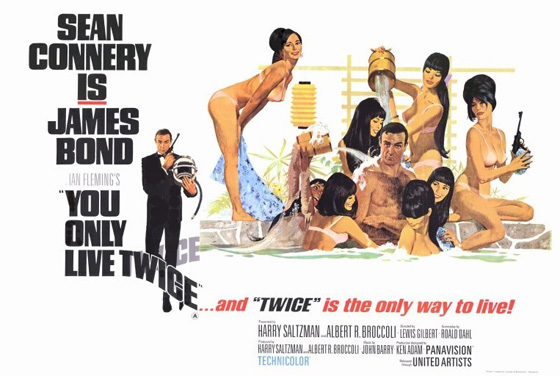

The fifth in the James Bond series produced by Harry Saltzman and Albert “Cubby” Broccoli, You Only Live Twice (1967) took 007 to Japan to finally confront Ernst Stavro Blofeld, the shadowy “Number 1” in prior outings, face-to-face. Blofeld appeared in a trilogy of Fleming novels, Thunderball (1961), On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1963), and You Only Live Twice (1964). I’ve previously expressed my regret that OHMSS – one of the most important passages in the life of James Bond – wasn’t adapted sooner (it was originally scheduled to be the next film after Goldfinger), but forgoing the middle chapter of the Blofeld trilogy for its climax only rubs salt in the wound. Admittedly, Bond’s film continuity has always been problematic. So has the films’ fidelity to the source material, and YOLT continues the series’ gradual departure from Fleming with the most egregious changes yet. Screenwriter Roald Dahl – yes, that Roald Dahl, the author of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and an old friend of Fleming’s dating back to their work for British Intelligence during the war years – largely ignores the original novel save the broad outline that Bond is now headed to Japan to confront Blofeld. This may have been the most appealing aspect of the novel for EON Productions. Bond, nicknamed “Mr. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang” in Japan, was a phenomenon there and ripe for further exploitation. The new film would be produced with the assistance of storied Toho Studios, and two of their contract starlets, Mie Hama and Akiko Wakabayashi, were loaned to EON to be authentically Japanese Bond girls.

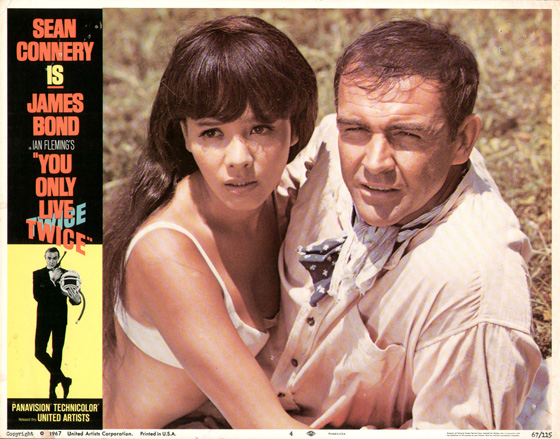

Mie Hama as Kissy Suzuki, Sean Connery as James Bond.

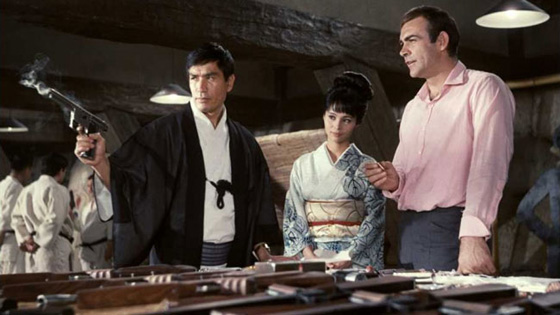

Their casting points to one of the film’s main pleasures: if it’s not a complete immersion into Japanese culture, at least it’s an open-armed, slightly naive embrace that’s endearing. Consider that in Dr. No (1962), French/Irish actress Zena Marshall donned makeup to appear Asian. So YOLT was progress – even though we are treated to a ridiculous scene in which Bond is given his own Japanese makeover to go undercover as a fisherman, a sequence that unintentionally emphasizes that it takes more than eye-makeup and a haircut to make a Caucasian look Asian (in the end, Sean Connery still looks like Sean Connery). We get glimpses of Tokyo streets quite different from those we know today, sumo wrestling, a Japanese wedding ceremony in a small fishing village, and – yes – lots of ninja action, foreshadowing all the ninja movies of years to come. But it does seem at times that 007 might be enjoying the culture for the wrong reasons. Memorably, Bond and his contact with the Japanese secret service, “Tiger” Tanaka (the appealing Tetsurô Tamba, Harakiri), are treated to a bath and massage courtesy a number of beautiful Japanese women clad only in underwear. “In Japan,” says Tanaka, “men come first, women come second.” “I just might retire here,” says sexist dinosaur James Bond. Regardless, there’s plenty here to appeal to Japanese audiences, as surely Broccoli and Saltzman intended. The cocktail of quasi-futuristic technology, style, cool, violence, and sex, were all guaranteed to win at the Japanese box office, especially for a market that was already producing their own Bond knock-offs.

Fleming loved Japan, and it comes through in the novel, though Dahl found it to be little more than a travelogue and greatly lacking as an exciting adventure. He wrote his screenplay quickly, applying a space-race theme not present in the original novel. Blofeld has built a rocket which can open up and swallow spacecraft whole, for the purpose of escalating Cold War tensions among nations that suspect each other of the act. The plot has an antecedent in the missile “toppling” performed by Dr. No in both the novel and film adaptation. In fact, Dahl’s approach to writing a Bond adventure was simply to decipher the formula from viewing previous 007 outings, which explains the story’s resemblance to that of Dr. No and, to a certain extent, Thunderball (1965). Originality and logic were not primary concerns. He told journalist Tom Soter, “Bond has three women through the film: If I remember rightly, the first gets killed, the second gets killed and the third gets a fond embrace during the closing sequence. And that’s the formula. They found it’s cast-iron. So, you have to kill two of them off after he has screwed them a few times. And there is great emphasis on funny gadgets and love-making.” So to fulfill the sex quotient we are given Hama, Wakabayashi – who inexplicably falls head-over-heels in love with Bond – and red-headed femme fatale Helga Brandt (German actress Karin Dor, star of various Edgar Wallace krimis), essentially a carbon-copy of Fiona Volpe from Thunderball, but given less to do and who subsequently has less of an impact. Brandt has an opportunity to interrogate, torture, and kill 007. Instead, she unties him, makes love to him, takes him on a ride in a plane, then sets it on fire and ejects, because that is how a SPECTRE agent does things. No wonder that Blofeld keeps feeding them to his piranhas. Oh, I forgot to mention: Blofeld has a piranha tank in this one, and a bridge crossing them, with no railing and a trap door that he can trigger with the press of a button. The fish are kept well fed.

"Tiger" Tanaka (Tetsurô Tamba) shows Aki (Akiko Wakabayashi) and Bond the latest weapons and gadgets of the Japanese secret service.

Though I find Dahl’s screenplay condescending, there’s quite a lot to enjoy here. In addition to all the beautiful location shooting in Japan, there’s a fun cameo from Q (Desmond Llewelyn), dropping by in knee-high socks to deliver “Little Nellie,” a gyrocopter that can be assembled from suitcases. This leads to an aerial combat sequence that attempts to top the Aston Martin car chase in Goldfinger. (It doesn’t quite succeed, but that’s OK.) The film also boasts a pre-credits sequence that’s the best the film had given us to date. After some big-budget FX depicting Blofeld’s spacecraft capturing an American vessel in orbit, Bond is introduced in bed, locking lips with a Chinese girl and pondering why Chinese women taste different from other women, “like Peking duck is different from Russian caviar.” “Darling, I give you very best duck,” promises the unsubtle girl, before flipping a switch that causes Bond’s bed to fold against the wall. Chinese gunmen storm the room and open fire. When the bed is pulled back down, Bond appears to be dead, the sheets beneath his body stained with blood. (It’s all been faked, of course, but it’s a great cliffhanger.) This is followed by another dazzling Maurice Binder credits sequence – all volcanoes and nude geisha girls – and one of the best theme songs of the entire series, sung by Nancy Sinatra of “These Boots are Made for Walkin'” fame. This song, with lyrics by Leslie Bricusse, was composed by John Barry. In attempting to apply an Oriental flavor to the theme, Barry stumbles across a romantic, luxuriant sound that would come to define his later scores, such as Out of Africa (1985) and Dances with Wolves (1990). The emphasis on romance is crucial to this film’s success, combating Dahl’s smirking double entendres and adding the necessary weight to Bond’s quick-fire relationships with Wakabayashi’s Aki and Hama’s Kissy. As with all his Bond scores, he takes the title song and twists it into different shapes as an instrumental backdrop for on-screen action. A slightly more up-tempo version plays during the most innovative of the film’s action scenes. As Bond races across a rooftop at a Japanese wharf, baddies emerge from every corner, and he pauses only to trade a few punches while hardly checking his gauntlet-run. Quite contrary to editor Peter Hunt’s typical up-close-and-personal brawls, this is all accomplished in a single helicopter shot that pulls back and back, a counter-intuitive move – as much so as Barry’s overtly romantic orchestration – that somehow increases the excitement. It’s the film’s best moment because it flips formula on its ear.

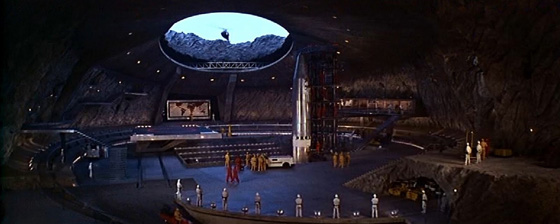

One of production designer Ken Adam's crowning achievements: Blofeld's volcano lair.

Ken Adam, having designed prior Bond outings as well as Dr. Strangelove (1964), tops himself yet again. It is the very definition of the series’ excess: Dahl wrote a volcano base into his script, Adam designed it and asked that it be built to his specifications, and Broccoli, Saltzman, and director Lewis Gilbert saw that it was. What you see on-screen seems impossible, but it really existed: a vast, 148-foot-tall interior, big enough to house a helicopter and helipad, a rocket, and a working monorail. This attention to spectacle ensured that the ubiquitous Bond copycats would remain just that – no one else could afford to pull this off without relying upon less convincing matte paintings or optical effects. (There are optical effects, of course, to help merge the Pinewood Studios set with the mountain exteriors. But when you see a swarm of ninjas rappelling down the interior of the volcano, the reality of the set’s scale is apparent.) As king of this castle – in Fleming’s novel, that’s literally what his headquarters was – Donald Pleasence makes an ideal Blofeld, granted some disfiguring makeup over one eye to make his final reveal more satisfying, Phantom of the Opera-style. It’s disappointing that Pleasence didn’t return in the role, though, as we shall see, the next film is almost a reboot of the series, with Bond and Blofeld (now Telly Savalas) meeting again for the first time. To further confuse matters, Diamonds are Forever (1971) gives us a Blofeld played by Charles Gray, a very recognizable actor who in You Only Live Twice plays Bond’s contact Henderson. The head spins to make sense of it all – so best not try. You Only Live Twice works best when viewed as Connery’s exit from the series, a finale to the first string of Bond pictures. It gives audiences what they’d come to expect from the series, only more of it and on a larger scale. Blofeld finally takes center stage, and is defeated by the hero. Once again Bond meets the ending credits in a raft on open water, a girl in a swimsuit in his arms. JAMES BOND WILL RETURN, the words still promised. Just not with Sean Connery. He’d grown tired of the character and he’d had enough…for now.