When I was a child, The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973) and Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977) were one and the same – a four-hour Sinbad miniseries, with all the islands, wizards, beautiful girls, and Ray Harryhausen monsters randomly distributed so that I wasn’t exactly sure which belonged to which. Understand that every trip to the video store meant that I would stand there, staring at all the boxes, ruling out the R-rated films or anything that looked remotely adult (verboten when I was a child), and eventually, inevitably, I would grab a Ray Harryhausen movie and hand it to my mother or father, who would just say, “This one, again?” Jason and the Argonauts (1963), Mysterious Island (1961), or a Sinbad movie. These films were the foundation stones upon which my imagination was built. Even though the early 80’s belonged to George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, I always held the Harryhausen films in special regard. Before I even learned his name, I knew these films were connected – I recognized the stop-motion animation and the look of the monsters. (Of course that centaur only has one eye. He’s probably related to those cyclopes in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad.) These films had special special effects. Having watched just about every non-R-rated fantasy movie on the video store shelves, I knew there was a significant difference between One Million B.C. (1940), the Victor Mature movie with lizards and armadillos posing as dinosaurs, and One Million Years B.C. (1966), the remake with Harryhausen’s pterodactyls lifting Raquel Welch off the ground. You can’t dress a lizard up to look like a pterodactyl. The funny thing is that I was appreciating the films from a point-of-view that was already becoming outdated. The days of stop-motion were coming to an end, with his swan song, Clash of the Titans (1981), released around the time that I was just beginning to appreciate his films. Though both Lucas and Spielberg used stop-motion effects in Star Wars (1977) and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), by the end of the decade The Abyss (1989) would announce a new direction for cinema tricks.

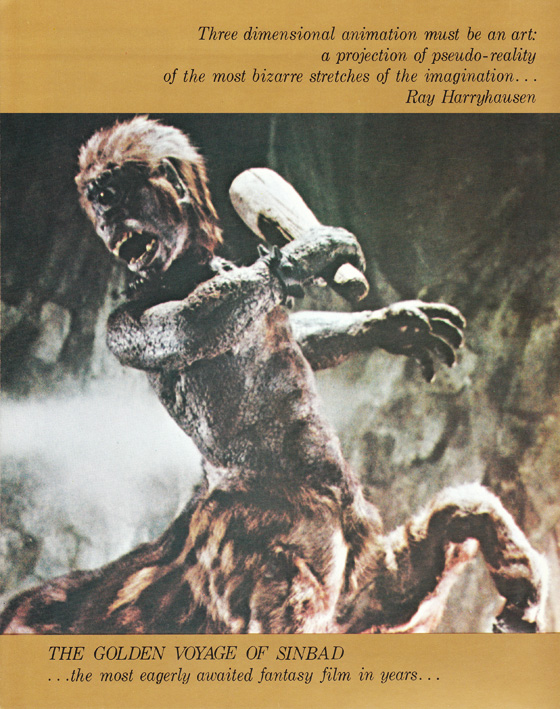

Cinefantastique back cover, Fall 1973 issue.

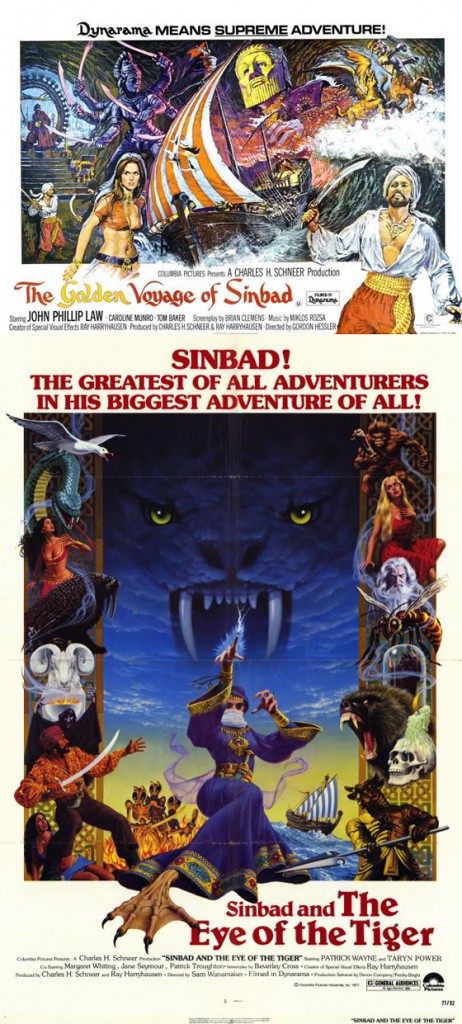

Twilight Time has just released The Golden Voyage of Sinbad and Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger on Blu-Ray, following their standard model of limiting the number of units produced (in this case, 3,000, so grab them now, before they go for exorbitant sums on eBay). It’s appropriate that they’re releasing both at the same time, so you can program your own four-hour marathon, letting all the adventures pleasurably blur together. But Golden Voyage is the more popular of the films by far, fondly remembered by monster-kids who saw it in theaters. I suspect part of this is timing. The film was released in 1973, and was a nostalgic throwback to matinee movies of the 50’s and early 60’s, in particular, of course, Harryhausen’s own The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958). His output was beginning to slow a bit, attributable to difficulties in securing financing for the latest “Dynamation” feature; so Golden Voyage, to a certain set, was an event picture. (Cinefantastique wrote in advance of the film’s Christmas premiere, “This could be the runaway success that the [stop-motion] animation genre so badly needs to survive and flourish.”) It was also released during a rather dire period for fantasy pictures, most of which were low-budget, with cheap-looking FX and limited imagination. Golden Voyage had a slim budget (the final cost was $982,351), but features some fantastic stop-motion work to prove that Harryhausen’s energies hadn’t flagged. It also boasts a cult-film dream cast of John Phillip Law (Barbarella, Diabolik) as Sinbad, Tom Baker (soon to be starring in Doctor Who) as the villain Koura, Caroline Munro (Captain Kronos – Vampire Hunter) as the voluptuous Margiana, and Martin Shaw (currently starring in the Inspector George Gently series) as Rachid, with an uncredited cameo by Robert Shaw (From Russia with Love, Jaws), deep inside grotesque makeup playing the Oracle of All Knowledge. There’s really nothing here to dislike, and critics and audiences greeted the film warmly, ensuring a sequel.

Sinbad (John Phillip Law) and his crew, including the Vizier in his golden mask (Douglas Wilmer) and Margiana (Caroline Munro), arrive at the lost island of Lemuria in "The Golden Voyage of Sinbad."

Harryhausen, who made this film with his longtime collaborator and co-producer Charles H. Schneer, was careful to separate this film from 7th Voyage; he seemed to dislike the label of “sequel.” (In his 2003 book An Animated Life, Harryhausen states that he and Schneer even “strenuously” tried to avoid the term regarding Eye of the Tiger, curiously enough.) Indeed, the viewer need not have seen the former film, though naturally it exists in its shadow. The 7th Voyage of Sinbad is a classic of fantasy filmmaking to stand beside its chief inspiration, The Thief of Bagdad (1940). Golden Voyage is just another fun Harryhausen movie, the perfect way to pass a Saturday afternoon. Law does a credible job as our new Sinbad (replacing 7th Voyage‘s Kerwin Mathews), embodying Harryhausen’s image of the Arabian Nights hero: handsome, athletic, but not a bodybuilder. The story, conceived by Harryhausen and revised, polished, and scripted by Brian Clemens (of the TV series The Avengers, as well as Captain Kronos, which also featured Caroline Munro), sends Sinbad on a treasure hunt on behalf of a disfigured Vizier in a golden mask (Douglas Wilmer, Jason and the Argonauts). Their quest involves retrieving the lost pieces of an amulet, which will point the way to an ancient, magical source of great knowledge and power. There’s always an evil magician in pursuit, of course, and in this case it’s Baker’s Prince Koura, who controls gargoyle-like homunculi and lusts after the same prize. The story might be perfunctory, but it’s well-paced, with attractive location shooting in Spain to stand in for both the fictionalized Middle East and Lemuria. (Plans to shoot in India – which would have provided a wonderful look to the film – were discarded after hearing horror stories about “appalling red tape and bureaucracy” encountered by other Hollywood productions shooting there.) Composer Miklós Rózsa (The Thief of Bagdad, Ben-Hur) is the ideal stand-in for 7th Voyage‘s Bernard Herrmann, capturing the appropriate “Orientalist” feel.

A statue of Kali comes to life to attack Sinbad.

Harryhausen’s creations include the winged, miniature homunculus; an ensorcelled figurehead that tears itself loose from Sinbad’s ship; a one-eyed centaur; a gryphon that guards the Fountain of Destiny; and, most impressively, a six-armed statue of Kali which performs an Indian dance before dueling against Sinbad’s men with six swords. It’s really the Kali sequence that makes this such a memorable film. With his typical attention to detail, Harryhausen hired an Indian dancer (Surya Kumari, also a noted actress and singer) to choreograph and perform as Kali with one of her students strapped to her back. The dance was then scored with Indian musicians, and the sudden switch in flavor (as our ears have already been conditioned to an hour or so of Rózsa’s romantic adventure music) is in synch with the charged, magical atmosphere of the statue coming to life. For the swordfight, nearly as elaborate as the celebrated skeleton battle in Jason and the Argonauts, stunt choreographer Fernando Poggi tied three of his men together to rehearse the action with the actors, then removed themselves and let the actors shadow-box before the cameras, with Harryhausen’s Kali to be added later. It’s a showstopping fight and, it must be said, far more rousing than the typical poke-with-spears action that so many Harryhausen action scenes become (or, in fact, the earlier scene with the ship’s figurehead). It’s one for the highlight reels.

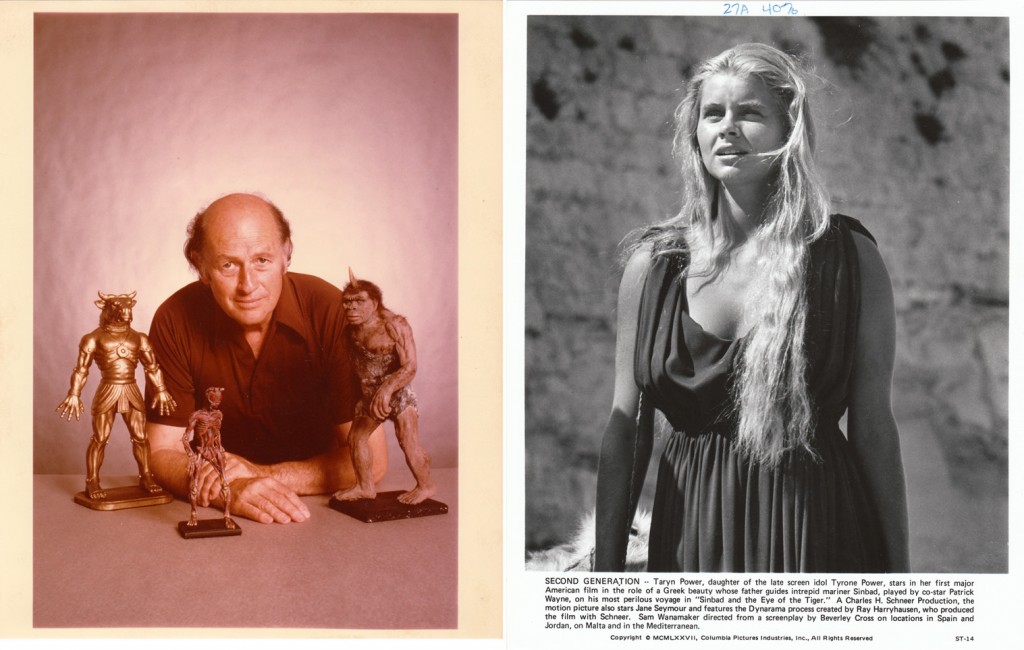

Publicity stills for "Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger": (L) Ray Harryhausen with his menagerie; (R) Taryn Power as Dione. (Click to enlarge.)

In An Animated Life, Harryhausen wrote about those directors who failed to understand his role in developing the film and directing its effects sequences: “Because the director didn’t fully realize my overall input or was used to ‘effects’ technicians only coming onto a picture toward the end of live-action photography, my involvement sometimes caused friction. The result was that one or two of them tried desperately to assert their authority, and at times it would seem as if we were shooting two different productions.” He proceeds to insist that Gordon Hessler, the director of Golden Voyage, was not one of those directors, and that the film was a happy experience. But such was not the case with Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger and its director, Sam Wanamaker. “Regretfully, he was probably not the ideal choice for a fantasy adventure, especially one in which he wouldn’t have complete control.” In The Art of Ray Harryhausen (2006), the artist says the film seems “tired and uninspiring,” that it was “put together too quickly,” and that it’s “the least satisfying of the three Sinbad movies.” Anyone who has read about Harryhausen’s method knows that he largely directed his own special effects scenes, as he had to: he needed to match what was in the camera with what he created in miniature in his studio, allowing the two worlds to be matted together as seamlessly as possible. This extended to dictating precise camera angles to create the illusion of his stop-motion figures interacting with the actors and set. If Wanamaker did not see to eye-to-eye with Harryhausen’s goals, as it’s inferred, the unfortunate decision to shoot most of the locations without the actors present – to keep the budget down – only made matters worse. It’s evident in too many of the scenes that the actors are in a studio far away. Some of the second unit location shooting, which included Jordan’s ancient city of Petra and the snowy Pyrenees, took place even before the casting had been completed.

Sinbad (Patrick Wayne) and his companions (including Jane Seymour, Patrick Troughton, and Taryn Power) discover Hyperborea.

Despite these flaws and others, the unkind reviews it received, and its poor reputation among Harryhausen fans, I still like this movie. The story, by mythology expert Beverley Cross (who wrote Jason and the Argonauts and would go on to write Clash of the Titans), is a lot of fun, taking Sinbad (Patrick Wayne, son of John Wayne) north to polar climes, and the legendary land of Hyperborea, here depicted as a prehistoric realm with a mystical pyramid at its center. Let’s focus on the positives. Although I’m not enamored of Wayne’s Sinbad (he may look the part, but that’s about it), the supporting cast is very good. Patrick Troughton, another Doctor from Doctor Who, is excellent as the wise alchemist Melanthius; British actress Margaret Whiting makes a strong female villain as Zenobia, a “wicked stepmother” plotting to replace the Caliph with her own son; and Jane Seymour and Taryn Power (daughter of Tyrone Power, and curiously getting higher billing than a former Bond girl) provide eye candy that seriously pushes the G-rating when they sunbathe in the nude before a startled Harryhausen creation, the Troglodyte (“Trog”). Trog himself is a very notable stop-motion creature – even if the horn in the center of his forehead is nonsensical – sympathetic with his fully-articulated face and expressive movements, and a subtle indication of how far Harryhausen’s art had advanced. But maybe his achievements here are too subtle, including the stop-motion baboon, the transformed Prince Kassim, that plays chess with Princess Farah (Seymour). What the film lacks is a tour de force moment like the Kali sequence in Golden Voyage, or the Medusa confrontation in Clash of the Titans. His intricate animation on Kassim the baboon – who begins to lose his humanity and resort to the nature of a beast – and Trog – who is more human than the beast he appears to be – is often overlooked by those who would rather see more spectacle-driven Dynamation.

Princess Farah (Jane Seymour) plays chess with her brother, who has been transformed into a baboon, in a scene inspired by a tale in "Arabian Nights."

But it’s hard to ignore that the story misses a very big opportunity by killing off the Minaton too soon. The creature is an eight-foot-tall bronze minotaur that single-handedly rows Zenobia’s ship to Hyperborea, only to meet his end when he’s crushed beneath a block that he’s pulled loose to gain access to the pyramid temple. Outside of Boba Fett, has any villain ever met such an abrupt and ignominious end? The natural resolution, and one the audience has every right to expect, is a climactic battle between the Minaton and Trog. This didn’t occur to Harryhausen until too late (as he laments in An Animated Life) – but it’s not like his other films are free of strange plot holes and missed opportunities. (I’m still waiting for Jason to kill King Pelias, a villain that the first half-hour of Jason and the Argonauts is spent establishing.) Ultimately, the big problems in Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger don’t really concern me all that much; I don’t find this to be as great a step down in quality as others argue, and there’s a lot in the film to enjoy. Just as nostalgia played a certain role in monster-kids loving Golden Voyage when it was released, so too does nostalgia allow me to see well past the faults of either film. The new Blu-Rays allow you to embark on one long wondrous voyage through Harryhausen’s imagination, with regular stops for secluded islands, ancient temples, ice-breaking walruses, green-skinned natives, bug-eyed ghouls, and chess-playing baboons.