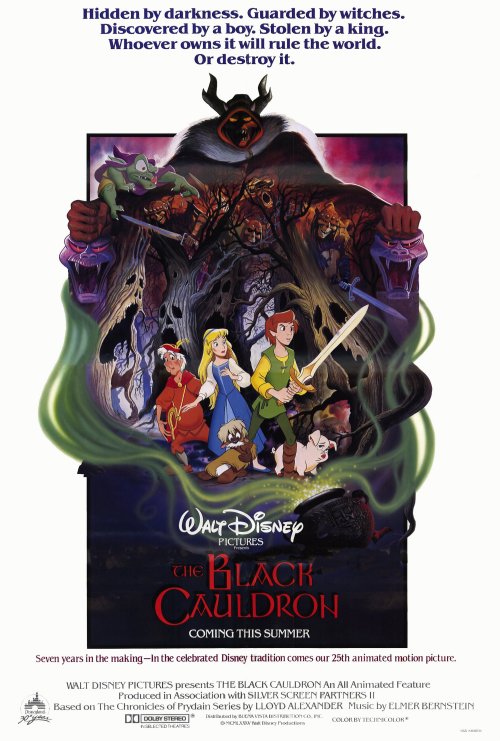

In 1985, I had a tremendous amount of anticipation for The Black Cauldron. Here was a Disney animated film based on the “Chronicles of Prydain” series by Lloyd Alexander, rated PG, and with magic swords, dark castles, and wicked witches; as a child obsessed with anything fantasy, and having read Alexander, I felt that the film was made especially for me. And it’s cool to have read a book before the movie comes out (the film draws from The Book of Three and The Black Cauldron, the first two books in the series); this was a relatively new experience, and I felt like an insider. So The Black Cauldron gave me a chance to say “the book was better.” I didn’t know that this disappointment, and this refrain, was such an essential part of being a consumer of pop culture, and here I was having my first taste. (Isn’t that a touching coming of age story?) My memory is that the film left me alternately dazzled, confused, and frustrated. I was highly conscious of the PG rating, which, for a Disney cartoon, was a much stranger thing then than it is now: animated films were for kids, and this film definitely had an edge to it. As someone who was becoming increasingly aware of female breasts, I was startled by a moment in which the comic relief bard Fflewder Fflam is turned into a frog and plunged straight into the ample bosom of the plumpest of the three witches, and seems about to be smothered to death in flesh. I was a child raised on Disney movies – as was tradition at the time, the classic films would regularly cycle back into theaters, and my parents would take me to every one. (That’s how I saw Song of the South. Disney wasn’t yet denying its existence.) This felt a lot more adult than Disney – dark, violent, scary, occasionally sexy – and I didn’t know how to process it. So not only did the film fail to faithfully deliver Lloyd Alexander, but it overwhelmed me in a way that I wasn’t properly prepared for.

Taran, Assistant Pig-Keeper, and Hen-Wen, the oracular pig.

The Black Cauldron is notorious, and not just for the cleavage scene and the gooey zombies. It’s notorious because it nearly killed Disney animation. The recent documentary Waking Sleeping Beauty (2009), about the resurrection of Disney’s animated studio, deliberately uses The Black Cauldron as its starting point – the nadir from which the studio needed to rise, the pit to climb out of in order to reach the heights of The Little Mermaid (1989) and those that followed. The film was a financial and critical flop. Critics were repelled by the creepiness of the subject matter (the Horned King is using the Black Cauldron to create an army of the living dead). Kids burst into tears at screenings. (Do we care about this anymore? I saw that happen during a showing of the first Harry Potter movie. There were sequels.) With evident apology, the studio turned quickly to lighter – and more musical – fare, like Oliver and Company (1988). The Black Cauldron had a troubled production history: as recounted at the Disney insider blog Jim Hill Media, Disney bought the rights to the Prydain books back in the 70’s, and let the project sit on the backburner while some young animators – led by Don Bluth – finally became fed up with Disney’s lack of ambition and left for a rival animation studio. So while Bluth forged ahead with The Secret of NIMH (1982), production on The Black Cauldron finally creaked forward under Ron Miller – then overseeing Disney’s production slate – and Joe Hale (a former Disney layout artist whose work dates back to Sleeping Beauty), with directors Ted Berman & Richard Rich (The Fox and the Hound). By the time a rough edit was assembled, a seismic shift had taken place at Disney: Ron Miller was out and Michael Eisner, Jeffrey Katzenberg, and Frank Wells were in. Katzenberg himself re-edited The Black Cauldron, removing several scenes he found objectionable, including a zombie slashing a throat and female heroine Eilonwy getting her dress ripped to shreds; eventually 12 minutes were cut. But although the final version wasn’t quite as dark, The Black Cauldron was still much too bleak for audiences and critics accustomed to innocuous Disney fare.

Eilonwy under assault in the Horned King’s castle.

Rewatching The Black Cauldron today, it’s clear just how ambitious a film this was, and how much it stands out from everything Disney had been doing in the years following Walt’s death. It’s also clear that the film is dreadfully flawed, and it hurts as much now as it did then, but for entirely different reasons. The Black Cauldron is very close to being a great Disney animated film. Very close – but it drops the ball (or, rather, the “bauble”). To begin with the positive, it is still refreshing, from the perspective of today, to see quality cel animation. I just watched The Lego Movie (2014), and as much as I enjoyed it, I wouldn’t want to hang a screenshot on my wall. Every frame of The Black Cauldron is gorgeously animated art, full of delightful character animation and beautiful, detailed, and immersive background paintings. The film is so visually appealing (shot in 70MM) that it’s heart-rending to think that hand-drawn animation is quickly becoming a lost art, one that requires a committed, well-staffed studio, and long, labor-intensive hours, to produce quality on this level. Also, one can see the effort being made to create a living fantasy world of real integrity – something on the level of The Lord of the Rings, which had slipped through Disney’s fingers and into Ralph Bakshi’s years before. (Ironically, there’s a Bakshi influence here. One scene, in which Taran the Assistant Pig-Keeper and his furry companion Gurgi stand atop a hill looking out at the Horned King’s castle, features a live action background of a sky with swirling blood-red clouds – like something out of Wizards or LOTR. And a round, cleavage-sporting wench in the castle, whose skirt briefly flips up to flash the audience with her panties, is certainly Bakshi-esque.)

The Horned King leads his Cauldron-Born forth.

The edginess, too, speaks of the film’s struggle to achieve some kind of sword & sorcery grit on par with other bloody fantasy films of the era, including Disney’s own – much more artistically successful – Dragonslayer (1981). There is a real sense of peril here, such as when Hen-Wen, a cute pig uncannily like the one in Charlotte’s Web (1973) – gets placed on a chopping block beneath an executioner’s axe, or when Taran and Eilonwy are cornered at a sealed drawbridge and axes and spears are hurled in their direction. Despite Bluth’s departure, the film actually feels more like his work than Disney’s. In its best moments, The Black Cauldron is wish-fulfillment for those of us who would have loved for Bluth to have made a feature-length film based on his animated Dragon’s Lair arcade game; particularly in those scenes where our heroes explore the Horned King’s castle, the Bluth approach to sword & sorcery adventure is on display, but even the mannerisms and expressive qualities of the characters feel like something out his films. The score is also quite good, and it’s by Elmer Bernstein, hot off Ghostbusters (1984). I was actually reminded of his work on Heavy Metal (1981), perhaps because the “Cauldron-Born” look very much like the zombies in a couple of segments from that film. There is a strong horror element in The Black Cauldron, and one gets the feeling that the animators really wanted to make an R-rated Disney film.

Fflewder Fflam, Taran, Eilonwy, and Gurgi discover the Fair Folk.

But for all its qualities, and as well as it’s aged, The Black Cauldron still just doesn’t quite click. Lloyd Alexander fans will find the film to be a mixed bag, as far as being an adaptation of his novels. The characters are well-realized, particularly Fflewder Fflam the bard, whose harp breaks a string each time he tells a lie – as with Gurgi, it’s almost like Alexander wrote him for animation; but the plot is a muddle. By squeezing together two separate novels into one long quest, and promoting the Horned King (really just a lackey to the series’ true villain, Arawn Death-Lord), it’s guaranteed to frustrate Alexander fans by getting as many things wrong as right. But what’s really missing is the author’s voice: his gentle and slightly bittersweet philosophical tone. In each episode of Taran’s adventures, there is a point, a lesson to be learned, a sacrifice to be made on his journey to adulthood: not so in the Disney film. Here, each sequence simply happens, and the characters are thrown pell-mell from one chaotic moment to the next. They rarely make decisions – and Alexander’s books are all about the hard decisions that one must make. Only in the final scenes, in which first Gurgi sacrifices himself, and then Taran attempts to trade his magic sword to bring Gurgi back to life, does one get a slight feel of the novels, but it’s too little too late. What drags The Black Cauldron down is simply poor storytelling. When writing a fantasy adventure, each moment needs to provide an opportunity for change or character growth. There is a dullness here, despite all its visual dazzle: it seems longer than it is. That’s because nothing really happens, and the characters, though well conceived, remain static throughout. You seldom laugh with them, or are given much of an opportunity to relate to them. It’s as though, in the rush to finally get this film off the ground, Ron Miller and company forgot to give the film a pulse. Yet, for all this, The Black Cauldron is a fascinating might-have-been. A few tweaks and it could have been a classic animated film, one that would have fit in well with other great 80’s fantasy movies; but also one that would have conjured the grim, spooky atmosphere of the Chernabog sequence in Fantasia (1940), stretched to feature length. Instead, it only gave a studio impetus to scrub away the shadows and produce films more mainstream and a good deal more wholesome.