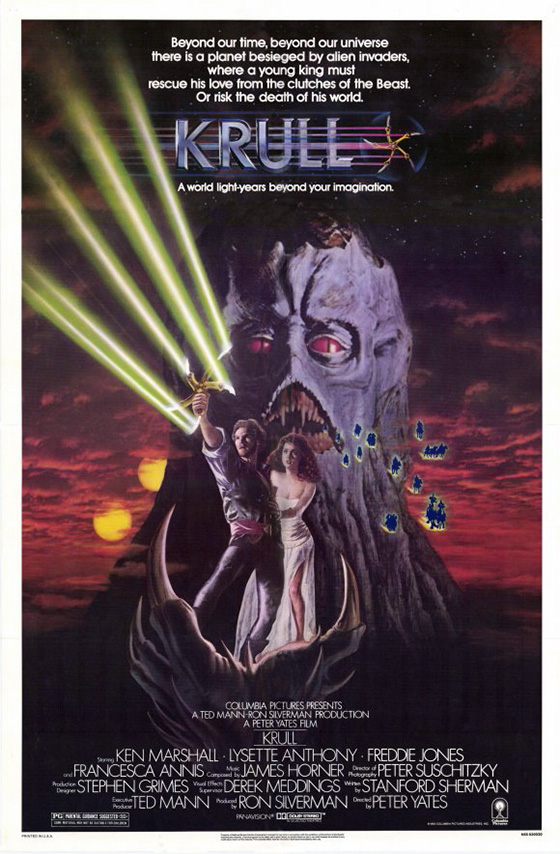

I never saw Krull (1983) in the theater, though I was aware of it – I have a childhood recollection of being mesmerized by a “making of” special on TV. But shortly after its home video release my father rented it, watched it on his own, and thus bequeathed it to me, mumbling: “You should watch this. You’d like it.” Well I did. I duped it VCR-to-VCR so I could have my own personal copy. My mother bought me the Krull Activity Book, so I could solve Krull puzzles. I played the Krull arcade game and never made it past the rock climbing. I drew the characters obsessively. For what seemed like many years, Krull was, to me, every bit the equal of the Star Wars films. When you’re that young and obsessed with fantasy and science fiction, whether a film features a cyclops is much more important than the qualities of the script. Even better, Krull was both fantasy and science fiction. The title is actually the name of a medieval-themed planet – with twin suns a la Tatooine – and the villainous Beast is an alien from another world. The Slayers, the black-armored, dome-headed alien creatures that serve as this film’s Stormtroopers, have spears that operate as blasters. They shoot bright blue beams and make pew-pew noises. And, of course, there is the Glaive, which is little more than an elaborate ninja star which the hero can control with his mind. Because it was the 80’s. But most of all – cyclops!

Princess Lyssa (Lysette Anthony) explores the Black Fortress.

When I revisited the film years ago, I was disillusioned. I had the dialogue and every beat of action so deeply ingrained from the numbingly repetitive viewing of childhood that nothing could surprise me, and worse, none of it was as good as I remembered: it was hammy and the plot and characters paper-thin. So on this latest viewing I approached with greater caution. The impetus was reading Michael Moorcock’s Elric fantasy novel The Vanishing Tower (1970), which features a fortress that appears in a world for only a brief period of time before magically relocating to another world, another dimension in Moorcock’s “multiverse.” And it all came back to me, like a repressed memory: the Black Fortress from Krull. It’s a very similar concept. The Black Fortress, which is simultaneously a castle, a mountain, and an interplanetary ship, teleports itself from one end of the planet Krull to the other at every sun(s)rise. Within dwells the Beast, and in one of the film’s clever conceits, we only glimpse bits of him directly, though the architecture suggests parts of his monstrous anatomy: a clawed hand, an eye, a spinal column, teeth. When the Beast and his Slayers capture Princess Lyssa (Lysette Anthony, Without a Clue), she tests the boundaries of the Black Fortress, wandering through its surreal corridors of organ-and-bone like an inner-space explorer in an H.R. Giger adaptation of Fantastic Voyage. The Beast itself, which seems heavily influenced by Giger’s Alien, is finally revealed in the climax, though director Peter Yates (Bullitt) depicts him through a distorting lens that stretches out his body and makes you feel like you’ve got your contact lenses in backward.

Rell the Cyclops (Bernard Bresslaw) and bandit Kegan (Liam Neeson).

The scenes in the Black Fortress are certainly the most visually striking and inventive, though much of Krull takes place in a gray, rocky landscape (shot on location in Italy) as Colwyn (Ken Marshall, of the 1982-83 Marco Polo miniseries) – a prince who has just become a king after the Slayers kill his father – launches a quest to rescue the princess. Offering guidance is the only other survivor of the castle massacre, the wise Ynyr (Freddie Jones, Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed), who tells Colwyn that his only hope in defeating the Beast will be acquiring the legendary weapon called the Glaive. This leads to a prolonged rock climbing sequence (fans of Mystery Science Theater 3000‘s Lost Continent, brace yourselves) before Colwyn enters a fissure in a granite wall and finds the Glaive in a stream of lava. Colwyn reaches in and retrieves the weapon unharmed – passing some kind of Arthurian test, it seems. With his Excalibur in hand, he faces his next challenge: trying to determine where the Black Fortress will appear next, and to catch up with it before it vanishes. He gathers allies along the way, including a comic-relief wizard named Ergo (David Battley, Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory) and a band of robbers so recently escaped from a dungeon that they still wear their manacles. The robbers are led by the jaded Torquil (an excellent Alun Armstrong, The Duelists). Among their ranks you might recognize Liam Neeson and Robbie Coltrane, though their screen time is unfortunately limited. Finally, Colwyn recruits the “Blind Emerald Seer” (John Welsh, The Revenge of Frankenstein), his boy assistant Titch (Graham McGrath), and Rell the Cyclops (Bernard Bresslaw, Jabberwocky).

The Crystal Spider, guarding the Widow of the Web.

The cyclops is a pretty cool creation, both in makeup design and in conception. It’s explained that his race originates on another planet, and his people made a bargain with the Beast: they would trade one eye to receive the gift of foresight; unfortunately, they’re only able to see the moment of their own death. So Rell is a gloomy creature, but also a loyal companion who quickly earns the warriors’ trust. As they travel across Krull, Colwyn’s company battles the Slayers, who squeal like rabid Muppets when they die, their dome heads cracking open as a bloody slug slithers off into the ground. They also face black-eyed “Changelings” – shape-shifters with long claws – in one of Krull‘s many scenes that feel more horror than SF or fantasy. To discover the location of the Black Fortress, Ynyr must brave a visit to the Widow of the Web (Francesca Annis, of Roman Polanski’s Macbeth), his ex-lover who now lives at the center of a giant cobweb spun by a Crystal Spider. The spider is some nice stop-motion animation from Steven Archer, who was one of Ray Harryhausen’s assistants on Clash of the Titans (1981). Colwyn and friends must also tame the Fire Mares, horses that not only travel so fast that fire sparks from their hooves, but have the gift of flight. It’s not until Colwyn confronts the Beast that he breaks out the Glaive, throwing it like a boomerang or a Tron discus, and since the Beast retaliates with bolts of light shooting from his jaws, it’s pretty obvious why the film was quickly adapted into a video game.

Invading the Black Fortress.

Krull, through adult eyes, is a very mixed bag. It has shining virtues and equally obvious flaws. On the downside is the script: the stale “rescue the princess” plot is told humorlessly, lacking the relative subversiveness of Star Wars (Princess Leia can handle herself just fine once she has a blaster in hand). Colwyn and Lyssa are the least interesting characters in the film, even though apparently their newlywed love is so strong that it allows Colwyn to turn his hand into a flamethrower, shooting lethal fire forged in their marital bond (yes, spoilers, that actually happens). Even Neeson and Coltrane, with only a few minutes of combined screen time, seem to have more defined characters to play. To be fair, Lysette Anthony, who has gone on to a solid acting career, does what she can with very little – but in an era in which big-budget pulp fantasy throwbacks made room for strong, fully-realized female characters (Princess Leia, Conan the Barbarian‘s Valeria, Dragonslayer‘s Valerian), the inattention to Lyssa is inexcusable. Make no mistake: this is a fantasy aimed at young boys, not young girls. And when I was a young boy, I wanted nothing more than to rescue the princess with a cyclops at my side and a Glaive on my belt.

Titch (Graham McGrath) and Ergo the Magnificent, transformed into a tiger.

Look past the bland Colwyn and Lyssa plotline and you’ll find that it’s the comic relief character that is the most rewarding- rather surprisingly, for a genre film. David Battley’s Ergo the Magnificent promises to be insufferable when he’s first introduced (accidentally transforming himself into a goose), but he proves to have more layers, first when he overcomes his superstitious fear to befriend Rell, and then as he begins to bond with young Titch. Ergo asks the child what he’d spend a wish on. Titch says he’d want a puppy. “Only one puppy?” says Ergo. “If you’re wishing, why not wish for a hundred?” “I only want one,” says Titch, and Ergo declares matter-of-factly, “Well, that’s a foolish wish.” When Titch is abruptly orphaned, the Emerald Seer slain by a Changeling, Colwyn smiles as he tells him, “We’re your family now,” and then walks away. (Gee thanks, Colwyn.) Ergo hides himself in the brush and uses a spell to turn himself into a puppy, which Titch, knowingly, holds close as they continue their journey. It’s Rell who catches the puppy slipping off quietly and transforming back into Ergo. “I still think it’s a foolish wish,” Ergo mutters to him. As a kid, that scene didn’t mean much to me. As an adult, that’s the moment that stands out more than the spectacular Pinewood Studio sets, the avant-garde art design, the genre-mashing special effects, or the grand score by James Horner (Aliens). More of that across the board, and Krull would have stood much taller in what was a golden age of fantasy spectacles.