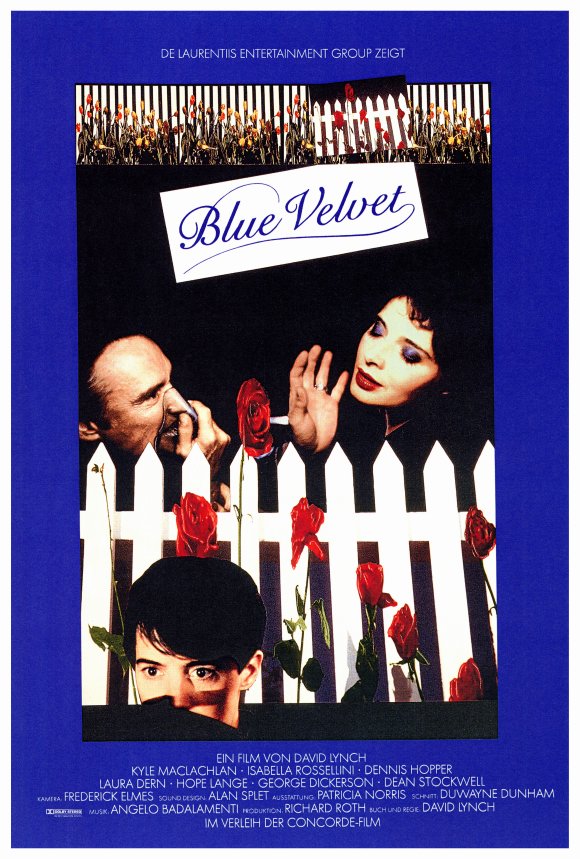

In some alternate reality, Blue Velvet (1986) must have been David Lynch’s sophomore feature film, following Eraserhead (1977). That seems most logical in retrospect, given the Lynch we know now. But in the nine years separating the films, Lynch embarked on a strange journey – perhaps not exactly like the one Kyle MacLachlan takes, but strange nonetheless. He is one of the eminent American auteurs, but he became, for a time, a steward of other people’s projects. For The Elephant Man (1980) he was recruited by executive producer Stuart Cornfeld to direct a script adapted from two books about the deformed John Merrick and his relationship with a caring surgeon named Frederick Treves. Lynch was an inspired choice, but it took the faith of Mel Brooks to get the film financed, under his production company Brooksfilms. Lynch wanted his Eraserhead star Jack Nance to play Merrick, but this was a bridge too far. John Hurt was cast instead, with Anthony Hopkins as Treves. And so the director of a notorious midnight movie had somehow found himself a prestige project; he was rewarded with an Academy Award nomination. Next he inherited Dune (1984), which had previously been attached to Alejandro Jodorowsky and Ridley Scott. Lynch wasn’t a science fiction fan, but he saw an opportunity to create a unique, self-contained universe, perhaps not too dissimilar from Eraserhead but on a larger scale. However, he was reined in by Rafaella and Dino DeLaurentiis – not to mention the source novel – and wasn’t given final cut. The result was a flop, and critically despised. In just four years, Lynch had risen to the heights of Hollywood success, and then, it seemed, plummeted straight back to the bottom. You’re only as good as your last film. So he looked for something personal, to return to the creative freedom he enjoyed with Eraserhead. He turned to one of his old scripts from the late 70’s, which had already been passed over by studios, and struck a deal with Dino DeLaurentiis. If he filmed the script on a budget of $6 million, accepted a cut in salary, and kept the running time to two hours or less, he would be granted final cut. He could be an auteur again, and those Lynchian obsessions and motifs which were teased in The Elephant Man and Dune could now flower, like Blue Velvet‘s opening shot, red roses springing up against white picket fences.

Lumberton, David Lynch’s fictional town occupied by lumberjacks, suburban families, and sociopaths.

Blue Velvet was the dividing line, the moment when critics and audiences could decide whether or not they were down with this David Lynch fellow. The main thing about Lynch is that he is not safe. His talent is evident; when the film was released, even the fiercest Blue Velvet detractors, including a viscerally opposed Roger Ebert, acknowledged his skills as a director. As with both Eraserhead and Blue Velvet, Lynch paints his horrors upon an exquisitely composed canvas. He’s fascinated by the Golden Age of Hollywood, and his films – at least until the low-res Inland Empire (2006) – look like they belong among them. Naturally Blue Velvet contains a lot of blues, but also erotically suffused reds. He stages suspense scenes with the elegance of Hitchcock, and the similarities to Rear Window (1954), Psycho (1960), and Vertigo (1958) are intentional. He pushes his suburban paradise well past the point of parody: the film is bookended by a fireman clinging to the side of a fire truck and waving to the camera, a winking summary of the film’s sunny, clean neighborhoods of perfectly manicured lawns, friendly crossing guards, and chirping robins. A conversation between MacLachlan’s Jeffrey Beaumont and police detective Williams (George Dickerson) mimics the stilted dialogue of 50’s B-movies. But signs of corruption begin to invade before perversion and chaos ensues. Jeffrey’s father suffers a stroke while watering the yard, convulsing while his dog obliviously drinks from the spurting hose. After visiting his father in the hospital, Jeffrey discovers a severed ear in a weed-covered field. Ants crawl over and inside it, like a Dalí painting. Lynch’s camera plunges inside, into darkness – one of Lynch’s many portals to nightmare and transgressive worlds, first used in Eraserhead but even featured in Dune. It’s not long before Dennis Hopper’s most indelible creation, Frank Booth, is huffing nitrous oxide (or something more alien) and screaming at us, “Don’t you fucking look at me! Don’t you fucking look at me!” Much later in the film, Jeffrey will quietly muse, “It’s a strange world, isn’t it?”

Sandy Williams (Laura Dern) and Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) team up to solve a mystery.

Jeffrey’s trip through the Lynchian portal is Deep River Apartments, seventh floor, apartment 710. He gets there with the help of Detective Williams’ daughter Sandy (Laura Dern, Mask), who overhears from her father that the severed ear might have something to do with a woman named Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini, White Nights). Sandy and Dorothy are the film’s polar opposites, whom Lynch pushes to much greater extremes than Betty & Veronica. Sandy, a blonde high school senior dating a football player, is the innocent and the optimist, at one point describing a dream of a world without robins, a world without love, remaining in darkness. “There is trouble till the robins come,” she insists. Dorothy, a brunette with an exotic un-Lumberton accent, sings “Blue Velvet” at the Slow Club, bathed in blue light against a red curtain. She’s nothing but trouble, and in her dismal apartment, a den of iniquity, there are no robins in sight. At the start of the film, Jeffrey is hovering at the edge of the world of darkness, Lumberton’s flip side, and when he climbs the stairs to the seventh floor he initiates an almost chemical process that Lynch traces through the rest of the film. Jeffrey’s world is stained by Dorothy’s, and vice versa: or as she puts it, “You put your disease in me.” First he is a Hitchcockian voyeur, like James Stewart in Rear Window. When he becomes trapped in Dorothy’s closet, he spies on her undressing, a transgression that becomes increasingly compromised with the arrival of Frank Booth (Hopper), who beats and berates her, then spreads her legs. Inhaling his gas, he stares under her blue velvet dress, repeats, “Mommy,” and “Baby wants to fuck.” Jeffrey watches with fascination while he rapes her. And then, after Frank leaves, Dorothy discovers Jeffrey in her closet, asks him to undress at knifepoint, and begins to sexually assault him. So begins their perverse relationship. Jeffrey claims he only wants to help her: Frank is holding her husband and son hostage, and has sliced off her husband’s ear. (Frank tells her, “Stay alive, baby. Do it for Van Gogh.”) When Jeffrey and Dorothy make love, she asks him to hit her. He keeps this world bottled inside when he meets with Sandy to report on his progress. Her biggest secret is keeping the chaste relationship with Jeffrey from her boyfriend. But Jeffrey’s secret is as containable as Pandora’s Box.

Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper) watches Dorothy perform “Blue Velvet” at the Slow Club.

Following the template of Hitchcock and film noirs like Out of the Past (1947) and Detour (1945), Lynch punches up the elements with harder sex and darker, explicitly expressed perversions, from Frank’s fetishizing of Dorothy’s blue velvet dress, to the uncomfortable coupling of Jeffrey and Dorothy, to the way Frank dons lipstick and kisses Jeffrey on the mouth. Much has been made of the film’s Oedipal and Freudian themes – Dorothy as a sexualized mother figure, Frank as an abusive father; and, by this reading, Jeffrey as the son who must kill his father to win his mother. But Lynch seems even more interested in the collapse of those walls that protect us in childhood. Of Eraserhead he has pointed out that when he lived in the city he felt much like Jack Nance’s character: the urban environment of that film is dominated by noise and decay, with peace and hope only offered in brief, imagined reveries. The film also embodies a fear of adult responsibilities, with pregnancy and child-rearing the film’s central horror. In Blue Velvet, the sanctity of the home, with its white picket fences, green lawns and blue skies, is threatened by Jeffrey’s trips to the seedy part of town, which is presented as the same decaying, industrial world of Eraserhead. The film’s most shocking scene might be Dorothy’s intrusion into Jeffrey’s suburban sanctuary. He’s about to fight Sandy’s jock boyfriend – about as violent as things seem to get in that side of Lumberton – when Dorothy emerges from the background, striding across a front lawn completely nude, battered and bloody and declaring her love for Jeffrey. This was inspired by an incident Lynch witnessed in his childhood, and he aims to make it as upsetting for the viewer as the real-life event was for him. As one shot reveals to us, below those perfect square lawns and impeccably arranged flowerbeds seethe the black insects of nightmares.

Frank’s friend Ben (Dean Stockwell) lip synchs to Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams.”

And of course the film feels like a lucid dream. It is a dream of old Hollywood, a dream of Hitchcock and film noir and torch singers in the night club and crime shows always on the TV. Characters are coded mysteriously: Dorothy is “The Blue Lady,” and a corrupt cop is “The Yellow Man.” When Frank discovers Jeffrey in Dorothy’s apartment, he takes him on a symbolic trip into the darkest reaches of Lumberton, and things get even weirder. (Among his crew is Jack Nance as well as Dune‘s Brad Dourif. Lynch maintains a repertory company.) “This is it!” Frank announces, as they pull up to a house with a neon “This Is It” outside the door. Frank’s friend Ben (Dean Stockwell, also from Dune) wears a layer of makeup and speaks with the languor of one under the influence of opium; this is essentially his opium den, occupied by prostitutes and catatonics. He lip syncs to Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams.” As the film becomes more hellish it also becomes more fragmented. Frank screams and he and his crew vanish from Ben’s living room. They reappear racing at high speed along a Lost Highway, with no horizon, just pavement lit by headlights. Even at the film’s close, when Lynch returns us to suburbia and Jeffrey is lying in the sun, that chirping robin, who will trap a black insect in its beak, is obviously fake. The dream is continuing, and the contamination, the darkness, is just under our feet. For Blue Velvet, Lynch was validated with his second Academy Award nomination as Best Director. But from here on out he would be exploring the pet obsessions established in Blue Velvet, in opium dreams lip syncing to numbers of his own choosing.