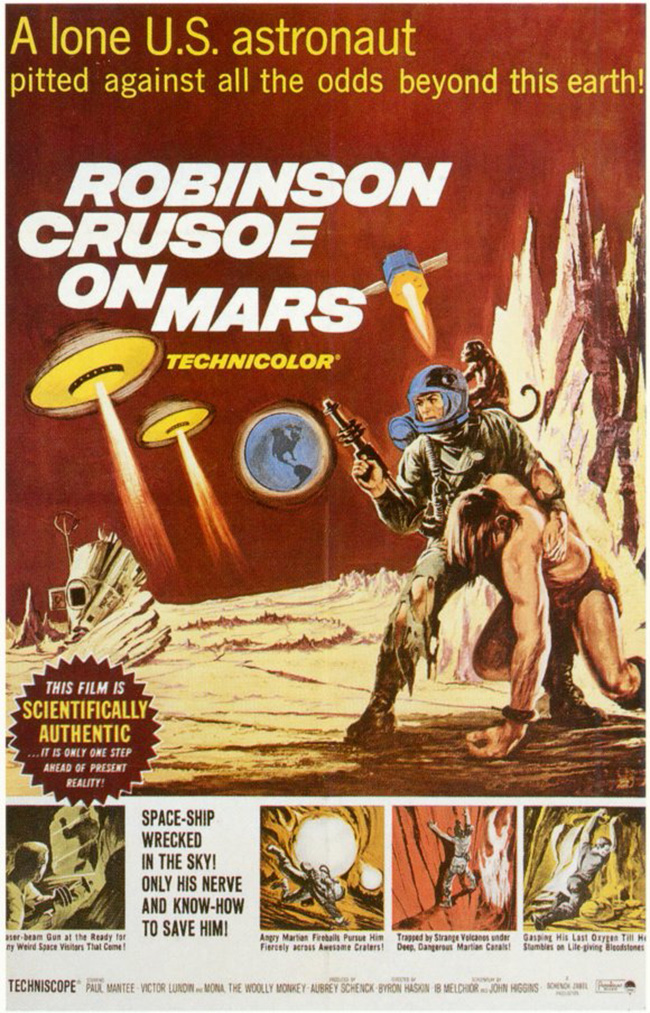

Even if you haven’t seen the film, you probably know the title Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964). It’s one of the all-time great titles, even though it sounds like a temporary one that the studio forgot to change at the last minute. (“Weren’t we supposed to call this Death Ship to Mars? Did you see the posters still say Robinson Crusoe on Mars? What happened, did we forget to tell Marketing?”) The title tells you everything you need to know. Conceived by Ib Melchior, the film was going to be the follow-up to his bonkers The Angry Red Planet (1959). He wrote the first draft of the screenplay and prepared an elaborately detailed series of sketches and storyboards in which the Crusoe character, trapped on Mars, fights giant Martian insectoid creatures and builds complex survival tools using all the resources he can scavenge. When Melchior was sidelined by directorial duties on The Time Travelers (1964), the project was handed to Byron Haskin, the 64-year-old director who got his start in special effects and technical work before directing films like the film noir I Walk Alone (1948), Disney’s Treasure Island (1950), and, for producer George Pal, The War of the Worlds (1953), The Naked Jungle (1954), and Conquest of Space (1955). Haskin set about making this science fiction Robinson Crusoe more serious. With screenwriter John C. Higgins (T-Men) taking a second pass, the Martian beasts were excised. An emphasis was placed on Mars as a barren world in which oxygen, water, and food are scarce, but solitude proves just as great a threat to Crusoe, now renamed Christopher “Kit” Draper. Under Haskin’s guidance, the film feels like a prestige B-picture, a worthy follow-up to War of the Worlds.

Mona the Monkey

The film begins just like all those Rocketship X-M-style B-movies of the 1950’s (albeit in lush Techniscope). Colonel Dan McReady (Adam West, pre-Batman) appears to be the typical square-jawed, serious-minded hero, staring at his console and speaking in technical jargon as the ship, the ELINOR-M, approaches the Red Planet. Only as an afterthought do we meet Commander Draper (Paul Mantee), poking his head out of the ceiling like one of those comic-relief characters that always seem to find their way aboard the ship. They even have a monkey in a spacesuit, “Mona.” But when a meteoroid intercepts the path of their rocket, they dive low toward Mars, and that’s when things begin to fall apart. Separately they eject. Draper lands in a crater filled with flames and fireballs. He takes shelter in a cave. Time passes. He runs low on oxygen. At about this point in the film the audience might realize that he’s now the protagonist, our “Robinson Crusoe,” and Colonel McReady is probably dead. Draper journeys into the desert-like wastes of Mars, the sky a piercing orange. When he finally discovers the colonel’s escape pod, it’s broken on a sharp ridge, and the colonel is buried under rubble. But little Mona still lives, so Draper takes the monkey on his shoulder and sets about the business of surviving. Yes, there will be a Friday – arriving in the third act, which delivers the requisite aliens and interstellar ships with laser beams. But all that only comes after a very long stretch as Draper fights off loneliness and tries to keep himself sane. In one eerie sequence, he hallucinates that McReady is still alive: a knock comes at the makeshift door to his cave, and it’s a zombie-like colonel at the other end, staring vacantly outward.

Robinson Crusoe on Mars is 110 minutes, which is long for a movie of this genre, made in this era. It feels like a capper to the age of space movies that began with Destination Moon (1950) and its ilk. Just around the corner was a different breed of SF: Planet of the Apes (1968) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). But even though Crusoe has one leg in 50’s pulp, it has another in the seriousness of what was to come. The best parts of Crusoe are those in which we’re right there with Draper, trying to solve some very desperate problems. How do you conserve your oxygen supply when you have to sleep? (Answer: build an alarm clock to wake yourself up when you’ve hit your limit breathing the thin Martian air.) But this makes you sleep deprived, so how do you cope? (The answer, apparently: make some bagpipes and play music.) Draper makes some life-saving discoveries: certain flammable Martian rocks produce a small level of oxygen, like rocket fuel. He finds a hidden grotto with a pool of water, fit for drinking and bathing, and at its base are seaweed-like plants that prove edible. Although the introduction of invading alien ore-miners is jarring (their ships are modeled after those in War of the Worlds), and the alien slave, Friday (Victor Lundin), ought to be played by an actor in costume or makeup – not just a loincloth – the film somehow keeps a grip on the survivalist theme and its somber tone. Lundin’s performance is very appealing, even though he is, essentially, the “noble savage,” and his arrival seems to evoke some colonialist attitudes from Draper, who teaches him about God and insists that he learn English. (Hey Draper, do you at least want to make an attempt to learn his language?) But they eventually bond, and by the end of the film, their affection for one another (and the monkey – never forget Mona) is actually touching. Byron Haskin finds the humanity in this science fiction story, which allows us to forgive the film’s weaknesses. It’s a visually striking little epic, laying the groundwork for more ambitious SF films to come.