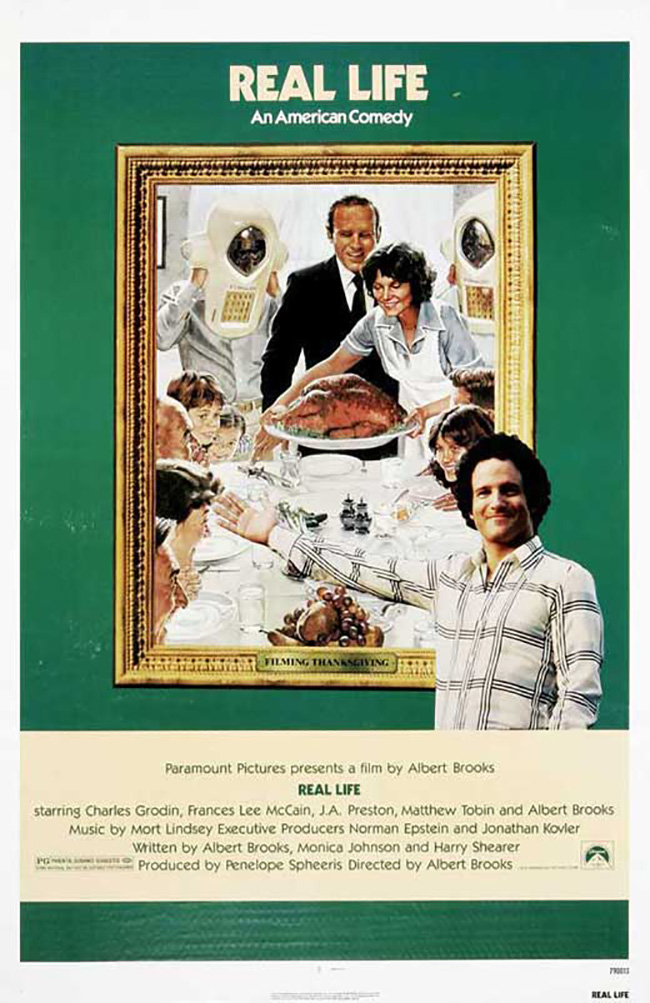

Albert Brooks’ Real Life (1979) wastes no time in admitting its inspiration; it’s right there in the opening scrawl. The landmark 1973 TV series An American Family, credited as being the first example of reality TV, was the product of a film crew documenting the day-to-day lives of an “average” American family, and ultimately capturing a divorce and the coming-out of one of the children. For his first feature film, comedian Brooks decided to take the documentary premise to “the next step.” Playing himself (or, rather, a hilariously exaggerated version of himself, a character wrapped snug in oblivious Hollywood vanity), Brooks conducts an experiment to film a family for one full year, editing the footage into a major motion picture. His head spinning with the Oscar potential, he only has one requirement: the family must be able to engage and entertain audiences. Bringing their own dramas to the dinner table is a must. At the same time, he reassures his chosen candidates, the Yeagers, that they can do no wrong – everything he’s capturing is “reality.” These conflicting desires must eventually collide, and they do, in a perfectly orchestrated escalation of neuroses and ego as scripted by Brooks, the late Monica Johnson (Modern Romance, Lost in America), and Harry Shearer (This is Spinal Tap, The Simpsons).

Albert Brooks (as himself) reassures family patriarch Warren Yeager (Charles Grodin) after Warren’s wife walks out on him.

Brooks introduces himself at the start of the film in a similar fashion to his famed short films for the first season of Saturday Night Live – the proving ground for his directing career. Reality is already slightly tweaked, right at the outset; this “Albert Brooks” is well known for his shorts on a show called Good Night Saturday. Teaming up with a pair of psychology researchers, Dr. Howard Hill from the National Institute for Human Behavior (Matthew Tobin, The Telephone Book) and Dr. Ted Cleary from the University of Minnesota (J.A. Preston, Remo Williams), he wonders if he’ll win a Nobel as well as that Oscar. Two hundred and ten families are interviewed, but it comes down to two that are perfect in every way. He chooses the Yeagers, who live in Phoenix, because the other family lives in Green Bay, Wisconsin. “You spend the winter in Wisconsin,” Brooks says. But we’re satisfied with the choice because the Yeagers are led by the irreplaceable Charles Grodin (Midnight Run) as milquetoast veterinarian Warren Yeager – a perfect straight man to Brooks’ manic monologues. While Brooks tells the family to “be yourselves,” he purchases a home across the street (his first, he says with pride) and orders his film crew to catalog every waking second of the Yeagers’ lives. The cameramen are wearing a state-of-the-art helmet camera which completely covers the head, has microphones for ears, and a round black lens for a face, like Errol Morris’ Interrotron reimagined by David Lynch. “Only 6 of these were ever made,” Brooks tells us. “Only 5 of those ever worked. We have 4 of those.”

Filming the Yeagers 24/7 with the “Ettinaur 226XL” camera.

Euphoric at the launch of the film, Brooks introduces the Yeagers to each member of the crew by their title – gaffer, A.D., and so on. When Warren’s wife Jeannette (Frances Lee McCain, Gremlins) asks what their names are, Brooks exclaims, “Not important!” Things fall apart at once. After getting into a fight with her husband at the dinner table (and complaining about her menstrual cramps, to her husband’s mortification), Jeannette decides to take some time away. Warren is apologetic to Brooks, but Brooks assures him everything is just perfect; this is “reality.” Jeannette offers to meet Brooks to negotiate her return to the house, and flirts with him. Things aren’t going as planned. Later, while Warren’s operation on a horse is being filmed, he’s so distracted by the film crew that he accidentally issues a lethal overdose. In his polite Charles Grodin-esque way, he asks Brooks to leave the scene out of the film, and Brooks assures him not to worry about it…while not making any promises whatsoever. It’s a brilliantly written and performed exchange that is right up there with the famed Garry Marshall bit in Brooks’ Lost in America. And Brooks continues to stampede over the lives of the Yeagers. After Dr. Cleary leaves in protest and writes a series of articles exposing the goings-on, news crews descend on the Yeager house. Jeannette says to Brooks, “The children are afraid to go to school.” His quick response: “That’s normal, believe me.”

Brooks delivers a Vegas-style musical number to get the city of Phoenix excited about his film.

Even with his first full-length film, Brooks – the real one, not the character – is adept at staging his satirical points. When Dr. Cleary decides to sit Brooks down, air his grievances, and leave the project, he tells him, “You’re getting a false reality here, and I don’t know what you’re going to do about it.” Getting nowhere, Cleary storms out. Brooks then looks over the table at the cameraman with the “Ettinaur 226XL” camera on his head, and states: “I was upset by Dr. Cleary’s sudden departure.” He could have shot the moment looking directly into the (actual) camera, but at this ninety degree remove, we get to see that ridiculous Ettinaur device one more time, and the absurdity is underlined. Reality erodes, and the fact that the entire project is all about Brooks and not the Yeagers becomes perfectly clear when he decides to manufacture his own spectacular finale, inspired by one of the most popular films of all time. (But not Jaws or Star Wars. He brainstormed those already. “How did they get a planet to explode?”) Even though An American Family had aired 6 years earlier, Brooks’ film was still prescient: reality TV as a genre was still a few decades away from reaching epidemic proportions. Perhaps Real Life kept them at bay for a while. The film summarizes the futility of trying to capture reality under the omnipresence of film crews. Over time, and with complete saturation, we’ve come to accept that artificiality for what it is, just as the stars of reality TV accept the presence of cameras and know just how to act “real” in front of them. By now, the blurred boundaries are as perplexing and natural as accepting the “reality” on display in Real Life by our host “Albert Brooks,” who, you know, isn’t really.

Note: as of this writing, all of Albert Brooks’ films, including Real Life, are now available on the U.S. Netflix. Now here’s something worth binge watching.