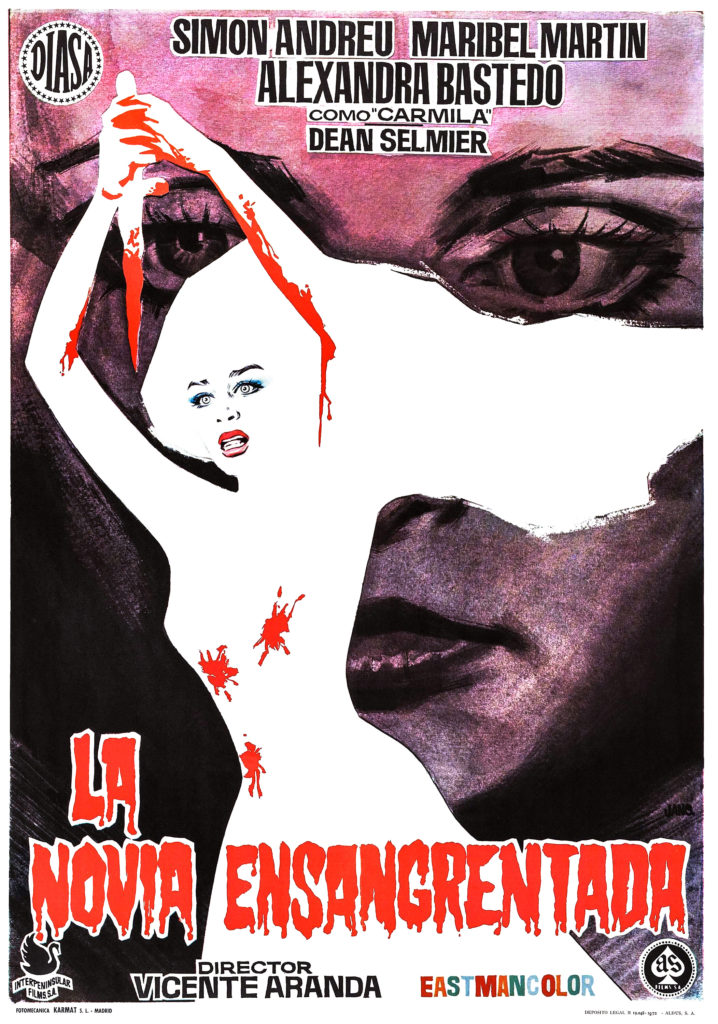

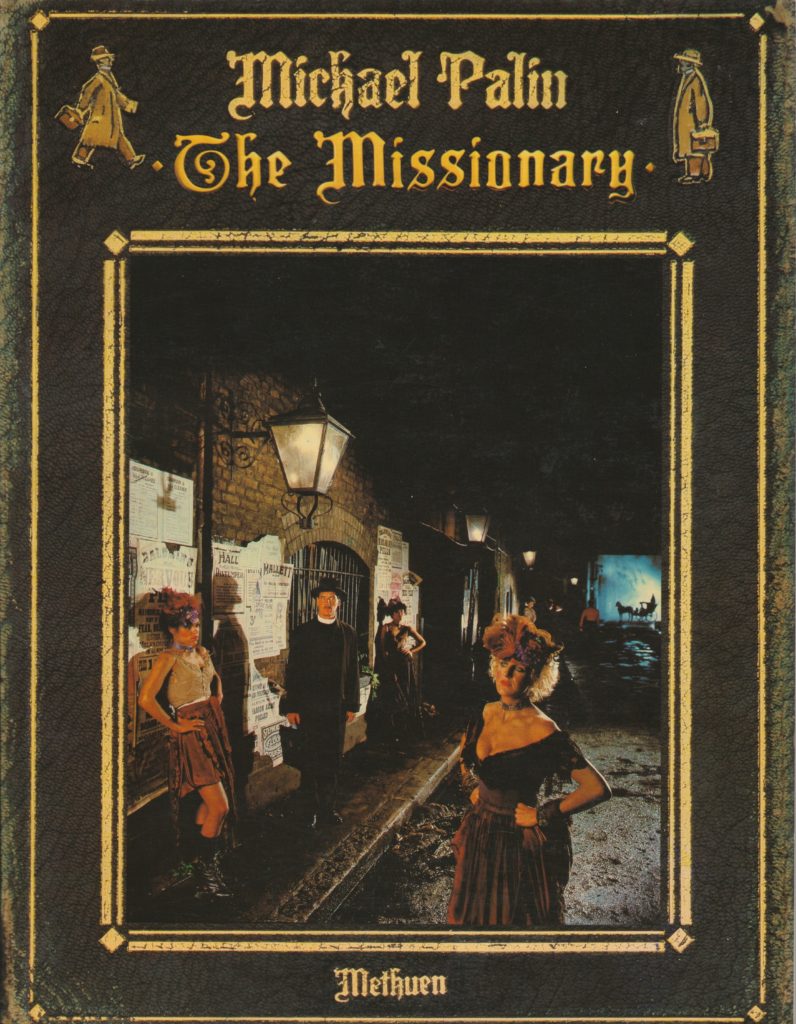

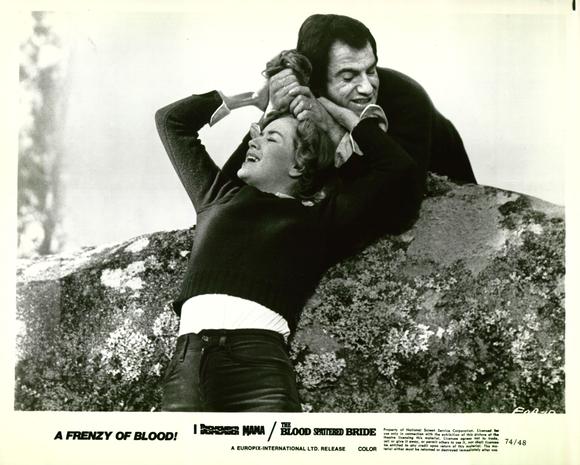

Hammer had just completed its Karnstein trilogy loosely derived from Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla when Spanish director Vicente Aranda (The Exquisite Cadaver) delivered a very different adaptation of the seminal vampire novella, La novia ensangrentada, aka The Blood Spattered Bride (1972). Artfully directed, swooningly photographed, and interrupted with unexpected moments of surrealism and bursts of frenzied sexual violence, the film is distinctive even in a market overstuffed, at the time, with sexy vampire movies. From the start we can see that the film has much on its mind: virgin bride Susan (Maribel Martín) is interrupted in her would-be honeymoon suite by a nylon-masked rapist, only for the assault to abruptly dissolve as her husband (Simón Andreu) opens the door, suggesting the encounter is either a paranoid fear visualized or a secret fantasy. The man in the mask bore an uncanny resemblance to her husband. The narrative proceeds just as conflicted, as though in active debate with its topics – feminism, pop psychology, chauvinism, the battle of the sexes – and never fully choosing a side. After the imagined attack, a shaken Susan asks to be taken back to her husband’s home, a rambling country estate near towering ruins. In the comfort of her husband’s bed, he rips open the dress of his new wife in the same manner she fantasized at the start of the film. She splays her arms like a crucified martyr, submitting to the defilement. Later, he corners her in an aviary, surrounded by fluttering wings and drifting feathers, like a fox in a henhouse – pressing her against the side of the cage before being interrupted by the maid’s pubescent daughter Carol (Rosa Rodriguez). Carol later asks Susan why he hurts her, and she’s taken aback by the suggestion; she tells the girl she loves him. But we also see the man, who is only given the name “El” in the credits and looks like John Cassavetes/Guy Woodhouse in Rosemary’s Baby, seize his wife by the hair and drag her up the side of a rock after surprising her in the woods. If they are playing games, this goes too far; she rebuffs his next sexual overture with the excuse that women are everything or nothing – and this time she will be nothing to him. All this and more before a vampire shows her fangs.

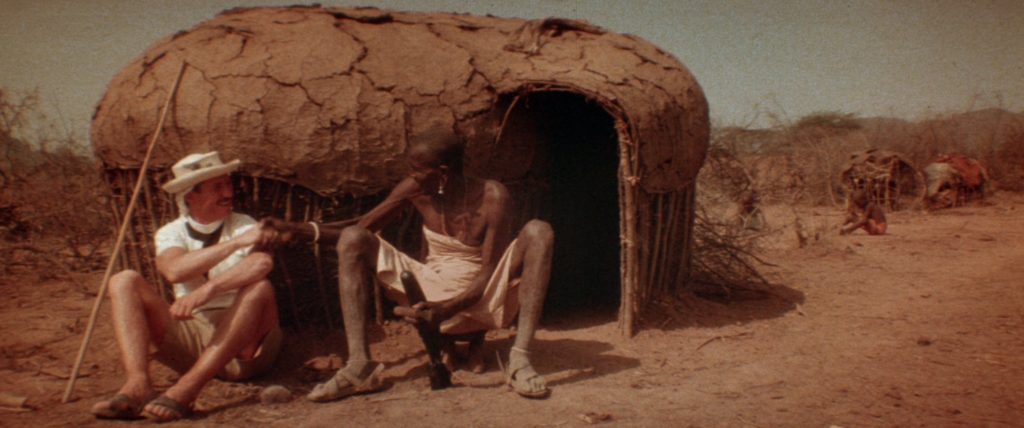

“El” (Simón Andreu) surprises Susan (Maribel Martín) violently.

The vampire, of course, is Carmilla (Alexandra Bastedo), known to the husband’s family as Mircalla Karstein. Susan first learns of Mircalla by discovering her portrait, committed to the basement with its face pointedly cut out and temporarily filled, in one of the film’s many strangely surreal images, with the face of young Carol, pulling a prank. Mircalla murdered her sexually abusive spouse on her wedding night, an act that seems destined to repeat itself when Susan begins receiving visions of Mircalla directing her to the hiding place of a sacrificial knife. This culminates in an ecstatically brutal stabbing – the camera fixed on Susan’s face rather than the wounds, and the hands of Mircalla guiding her – which is revealed, like the earlier rape, to be another fantasy bordering on premonition. He continues to hide the knife from her; she continues, uncannily, to find it. This leads to a burial of the knife in a beach, where the husband discovers Carmilla née Mircalla completely buried in the sand, breathing through a snorkel mask. Aranda first shoots the discovery from the perspective of Carmilla, gazing up through the mask. Then we see her face, purplish, dazed, as though she’s resurrecting before our eyes. No (proper) explanation for her beach burial is ever given; but whether she washed up or sprouted through the earth like a forgotten bulb, she seems to have been summoned by Susan’s arrival. The fateful visit to the beach signals a subtle shift in the narrative’s POV from Susan to “El,” which contributes to the film’s seemingly divided loyalties. As Carmilla begins to exert an unholy influence on Susan – Susan’s dream made flesh – “El” consults with a doctor (Dean Selmier) who dismisses his rising concern that something occult may be afoot. The doctor’s bland psychoanalytical explanations of Susan’s behavior are echoed in the literature which Susan discovers on the home’s bookshelves; she opens randomly to a page and the text accuses her of mental illness and hating her husband. Indeed, Susan’s actions increasingly seem borne on a chorus of voices – the doctor’s, her husband’s, Carmilla’s. Is she losing all autonomy, or finally gaining it? When the doctor tracks down Susan and encounters her consulting with Carmilla in the ruins like a sacred, secret ceremony, he seems just as alarmed by Carmilla’s declaration that Susan turn against her husband as the sight of teeth sinking deep into her neck, drawing blood. Later, he skips over this part when he recounts the scene for “El” – the point, he tells his friend, is that Carmilla is turning her against him. Vampirism is just a detail.

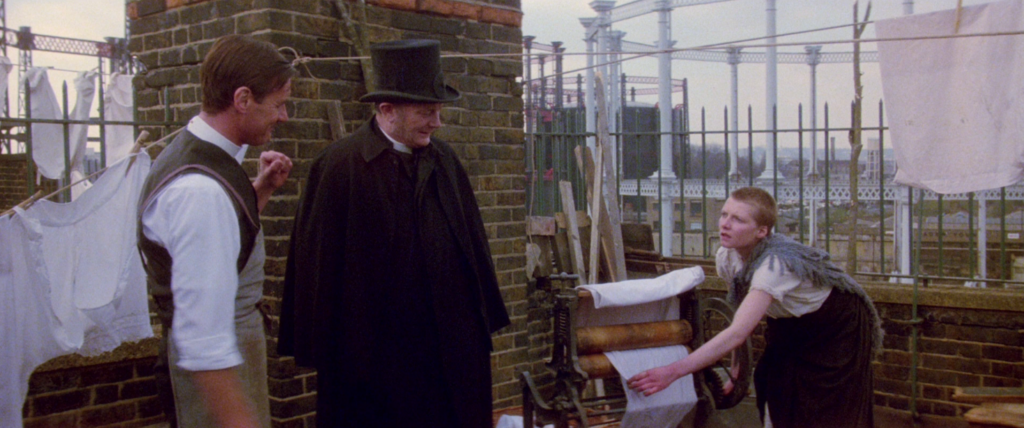

Mircalla/Carmilla (Alexandra Bastedo) in the trap.

Bastedo is a fascinating Carmilla, in a billowing purple dress which she sometimes wears as a cloak, occasionally suggesting the doe-eyed Yutte Stensgaard of Lust for a Vampire but in the critical moments displaying a roguishness and bloodlust. Her best moment comes when she’s caught in a trap set out for foxcatching; upon hearing the approach of the hunter, the pain is forgotten – she shoos Susan away and waits gracefully for the hunter’s arrival like a metamorphosed character in a Grimm fairy tale. When Susan stabs the hunter, Carmilla’s face melts with warm pride. Yet the film’s final stretch largely belongs to “El.” His execution of the vampires is brutally over-the-top (and, again, surreal, with a coffin spilling blood as he blows it to pieces with his rifle), so cold blooded that it’s clear his righteous mission is morally compromised. The film thus aligns itself with contemporary and future vampire films in which the crusading vampire killers are – subtextually or super-textually – the true monsters; though one could also argue his position, given that his wife is, you know, trying to murder him in his sleep. Sometimes Aranda’s restless imagination gets the better of him, as in a superfluous, illogical, but humorous little passage where Carmilla is revealed to be Carol’s classroom teacher, lecturing her young students on the properties (and taste!) of blood, or in a newspaper headline coda which is too abrupt to achieve any impact. Yet in the transgressive seas of 70’s horror cinema, The Blood Spattered Bride leaves deep marks.