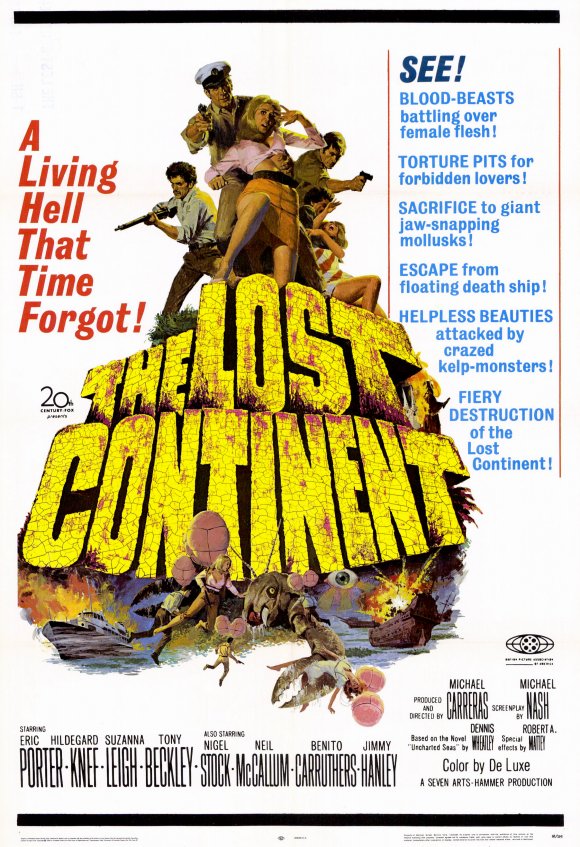

After taking one of the black magic novels of bestselling author Dennis Wheatley and turning it into a genuine Hammer horror classic – The Devil Rides Out (1968) – the studio next embarked on one of the author’s pulp adventures, 1938’s William Hope Hodgson-inspired Uncharted Seas. The result was retitled The Lost Continent (1968), a change that was unnecessary but also confusing, given the existence of Robert Lippert’s 1951 film The Lost Continent (released in the UK by Exclusive, the distribution company established by Hammer founding fathers William Hinds and Enrique Carreras) as well as 1961’s George Pal film Atlantis: The Lost Continent. Uncharted Seas, in my opinion, is a better title – and this is also a very different film than the others. Rather than presenting a rip-roaring matinee adventure, this is a weirdly depressive, alcohol-drenched voyage that drifts aimlessly into some very strange seas indeed. In an interview on Shout Factory’s new Blu-ray, film historian Kim Newman places this in what he calls the “ship of fools” subgenre – a group of strangers trapped together on a vessel, immersed in their own dramas despite the presence of catastrophe. What’s so odd is that in this case their little soap operas have absolutely no bearing on what happens to them; I could attempt to explain, for example, that Ms. Eva Peters (German actress and singer Hildegard Knef) is the mistress of the former president of Santo Domingo, that she assassinated him and stole “two million dollars’ worth of securities and negotiated bonds” to pay the ransom for her son, and that she’s been tracked down by an enforcer, Ricaldi (Ben Carruthers of The Dirty Dozen), except that all is quickly forgotten when they’re being attacked by flesh-rending tentacles of living seaweed. Her extremely convoluted backstory serves only to mark time until the film takes at least two jarring turns into different genres altogether.

The ship of fools and explosives, with Suzanna Leigh striking a pose.

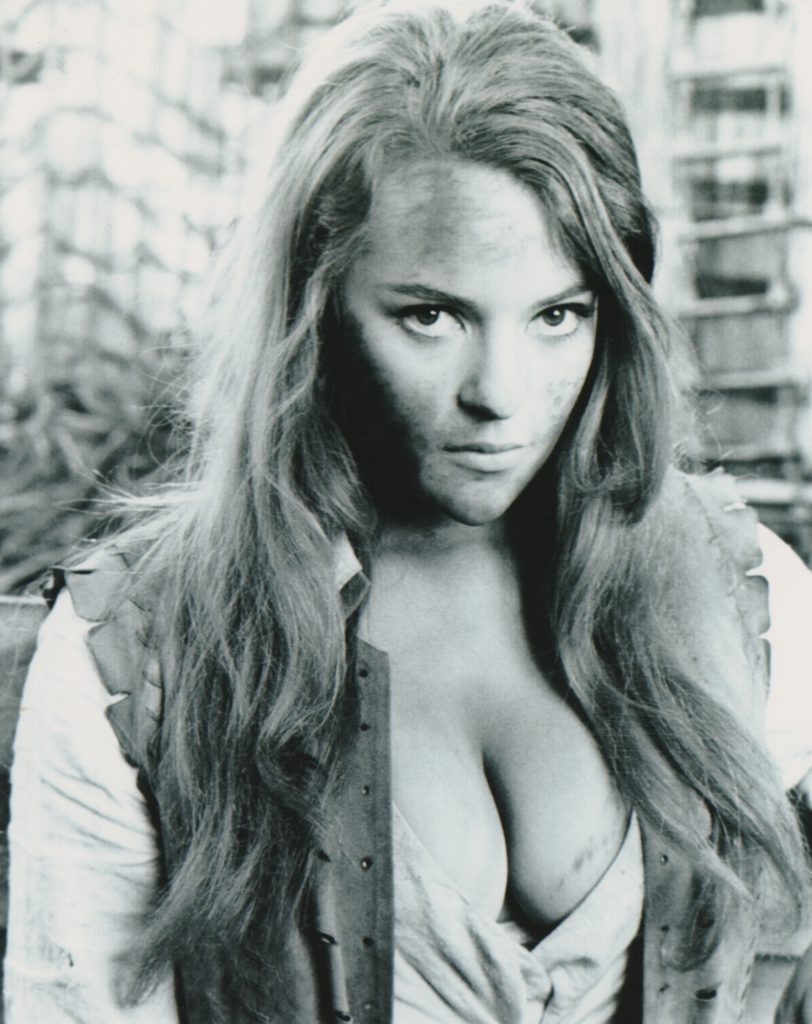

Joining Ms. Peters on this oceanic voyage from Freetown to Caracas are Dr. Webster (Nigel Stock, The Great Escape), his outrageously promiscuous daughter Unity (Suzanna Leigh), piano-playing cad Harry Tyler (Tony Beckley), a morally conflicted first officer (Neil McCallum), a bartender who looks kind of like Hammer regular Michael Ripper (Jimmy Hanley), the actual Michael Ripper (partially disguised by some scarring makeup over one eye), and a captain (Eric Porter) who’s smuggling “Phosphor B,” a dangerous explosive that’s ignited by – unfortunately for everyone involved – water. When McCallum and the crew discover their deadly cargo while sailing into a hurricane, they vote to abandon ship; but soon everyone is chipping in trying to haul the explosives out of the hold as it rapidly floods. Several take refuge in a lifeboat and ride out the storm, but become enveloped by a region of the Sargasso Sea choked with seaweed, some of which rises up to attack them. It’s here that they encounter the “lost continent,” a land mass where a giant crab and scorpion do battle. This realm is inhabited by leprous leftovers of the Spanish Inquisition, answering to the call of a boy king called El Diablo (Darryl Read), stealing the supplies of ships which become trapped in the seaweed and feeding their crew to a monstrous mouth beneath their galleon which resembles a cheaper version of the Sarlacc Pit from Return of the Jedi. Joining forces with our castaways is local revolutionary Sarah (singer Dana Gillespie), notoriously, hilariously introduced striding across the seaweed sea through the use of snowshoes and two giant balloons that offer symmetry with her colossal cleavage. In the film’s prologue, set at the end of the film, the narrator asks, “What happened to us? How did we all get here?” After watching the film, you may not be able to answer one or both of these questions.

“Hammer Glamour” publicity photo of Dana Gillespie as Sarah.

Hammer executive Michael Carreras, who would guide the company through its waning years of the 1970’s, wrote the script and eventually took over directing duties after the original director, Leslie Norman (X the Unknown), was let go. Carreras had produced some excellent films for Hammer, including Ten Seconds to Hell and Yesterday’s Enemy (both 1959), though his career as a director was decidedly more eccentric; Lost Continent would pair well with his previous film, the cheesecake Slave Girls (aka Prehistoric Women, 1967), for its straight-faced approach to material that’s off-the-charts absurdity. This film boasted a luxurious budget of £500,000 and tremendous water tank sets at Elstree Studios for the scenes of abandoning the ship and becoming stranded in the Sargasso Sea. The monstrous puppets were created by no less than Robert Mattey (Jaws, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea); though it must be said the giant crab and scorpion are ludicrous in appearance and bumbling in their movements, in a genre film that cries out for the involvement of a Ray Harryhausen or a Jim Danforth. The film is also saddled – or blessed – with a jazz-pop title song by the Peddlers, about as unconventional a choice for this type of film as one can imagine. And yet it sets the right boozy mood. This is not an escapist family adventure movie; it does, after all, spend about an hour lost in pointless melodrama as the various travelers bicker, make drunken passes, extort, and conspire, before the action finally arrives. Then everything happens so quickly that we struggle to keep up. There are conquistadors? Who’s El Supremo? Why the sudden shift into occult horror when just a second ago it was settling into the mood of a Japanese monster movie? And then it’s over just as it seems to have been getting started, leaving the distinct pangs of a hangover. This movie has fans. How can it not, with such sights and mood swings? But I’m always wistful at the oceanic horrors saga this could have been: when I first saw a bit of this on TV long ago, it was the moment when the crew are being attacked by a tentacular creature on their ship caught in the seaweed-clogged waters beneath a blood orange sky. Once I managed to see the entire film a few years later, I was disappointed – there was so little of what was so fantastic. A year later, Carreras produced Moon Zero Two (1969), another expensive flop for Hammer that spelled the beginning of the end of the company; it, too, features a delirious array of bad taste stampeding over a germ of a good idea. Depending on your point of view, as art these two films are disastrous or unexpected triumphs. And either way, watch it with a stiff drink.