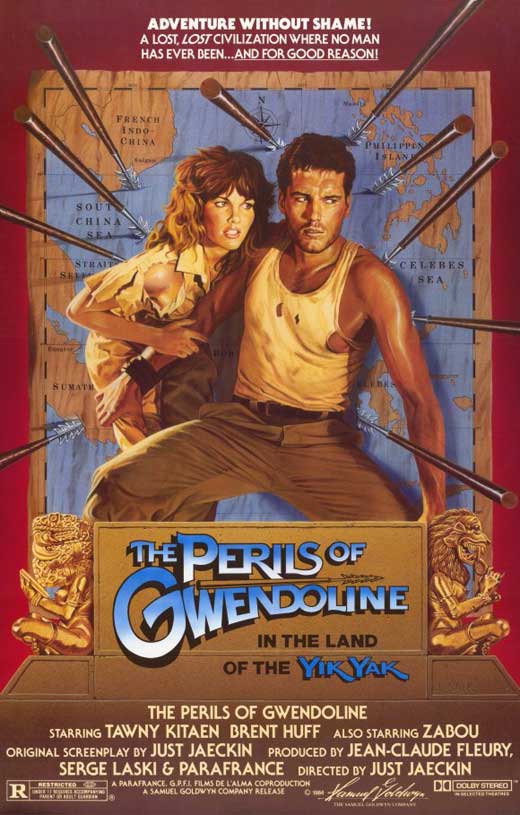

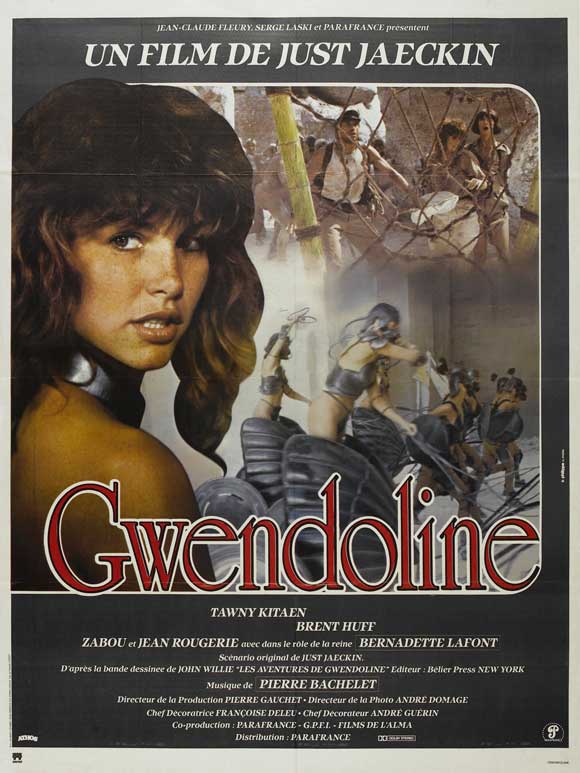

When The Perils of Gwendoline in the Land of the Yik Yak – in its native France known as Gwendoline (1984) – opened in the U.S. in January 1985, it received a healthy ad campaign and a wide release. I remember this because, though I was very young, I saw the ads everywhere and thought, That’s a movie I’d like to go to. It looks like Raiders of the Lost Ark. Of course, it was meant to evoke that Indiana Jones feeling, piggybacking on the 1984 hit Temple of Doom and featuring Raiders-style lettering on its posters (as just about every post-Raiders throwback adventure film was required to do). Here was your next Indiana Jones, Brent Huff, with a beautiful damsel holding tight to him, both glistening with sweat and wearing ripped shirts as they pose before a map of the South China Seas framed by jutting spears. And if “Yik Yak” indicated this wasn’t going to be a very serious film, all the better – it looked like fun. The fact that it was rated R ensured my parents kept me away, but what of all those other kids whose parents were less discriminating? The poster offered something of a warning as it declared: “ADVENTURE WITHOUT SHAME!” Years later I did catch up with The Perils of Gwendoline, on a whim browsing a video store, and by that point I’d at least had some warning that the movie was going to be a bit adult-oriented. Revisiting it again now, on a fine Blu-Ray from Severin which contains both its American Yik Yak release and the original uncut Gwendoline version, I’m struck by how embarrassed I am by this movie. It’s a completely personal reaction. Of course there are countless more explicit exploitation films. It’s entirely to do with remembering that wide multiplex release, suckering in the masses for a deeply fetishistic softcore bondage adventure-fantasy with almost uninterrupted naked flesh as presented by the director of Emmanuelle (1974), Just Jaeckin. Understandably, this would be Jaeckin’s last encounter with mainstream audiences.

Beth (Zabou), Willard (Brent Huff), and Gwendoline (Tawny Kitaen), captives in a village of cannibals.

The source material, not offering instant name recognition to mass audiences, was a BDSM-themed comic in the serial adventure vein called “Sweet Gwendoline” by John Willie, the pseudonym for photographer and artist John Alexander Scott Coutts, who in 1945 launched the influential fetish-themed magazine Bizarre. Choosing a comic like “Sweet Gwendoline” for a cinematic fantasy spectacle would seem to indicate Jaeckin was hoping for a similar cultural impact as Roger Vadim’s Barbarella (1968), itself based on an adult-targeted comic not too well known. Indeed, there are many similarities. Both films are from French directors with American actresses as the leads, leaning heavily on their pin-up sex appeal; both include pulpy, “comic book” style environs and clichés eroticized to the point of intentional camp; and both lean hard on their outré fashions and production design. But Barbarella landed in American drive-ins in the middle of the sexual revolution; the images of Jane Fonda in her sexy space gear, and the mere idea of a sexually liberated intergalactic adventurer – a flower-child in space – were more important than the film’s actual content. By 1984, Jaeckin’s own pop culture contribution, the soft-focus sex of Emmanuelle that lured curious couples into theaters (“X was never like this” boasted the posters over Sylvia Kristel’s parted red lips), was already a decade old. Those interested in viewing erotic content had plenty of options in cable and home video. It was filmmakers like Steven Spielberg who began to alter the marquees in the mid-70’s – Jaws arrived just six months after Emmanuelle – marginalizing the market for more provocative cinema; and now Jaeckin, of all people, was making his own Raiders. As only he could.

Gwendoline and Beth peek in on some opium den sex.

In a Chinese port, we first meet Gwendoline (Tawny Kitaen, Bachelor Party) locked inside a crate that’s opened by some surprised men searching the cargo. That she arrives packaged up in a box and, in the next scene, bound and gagged before a crime lord and his lascivious men at least indicates that Jaeckin knows how to establish his theme from the outset. She’s sought out by her faithful female companion Beth (Zabou) and finally rescued by amoral American smuggler Willard (Huff). Gwendoline is searching for her missing father, who journeyed to the land of the Yik Yak in pursuit of a rare butterfly. He reluctantly agrees to act as a guide only after he’s dunked the two of them and their baggage in the river twice, among other indignities. Gwendoline is not just a virgin, but somehow has never even been kissed; that she falls in love and lust with the indifferent, contemptuous Willard makes a barely-coded nod to a master/slave relationship. Beth acts as a doppelgänger for Gwendoline, so loyal to her friend that she experiences the same repressed sexual desires, which is treated for comedy when the three of them are tied up in the hut of a cannibal tribe. Willard, unable to touch Gwendoline except by brushing her lips with a piece of straw clenched in his teeth – an image which Jaeckin is never able to make sexy, try as he might – delivers an erotic monologue, but it’s eavesdropping Beth who gets off. A PG-rated joke works much more effectively a few minutes later: after escaping, the three find themselves encircled by cannibal spears again. A steaming-mad Beth, impatient with the lack of narrative progress, scolds the tribesmen and leads a march past their bemused stares.

The desert journey to Yik Yak.

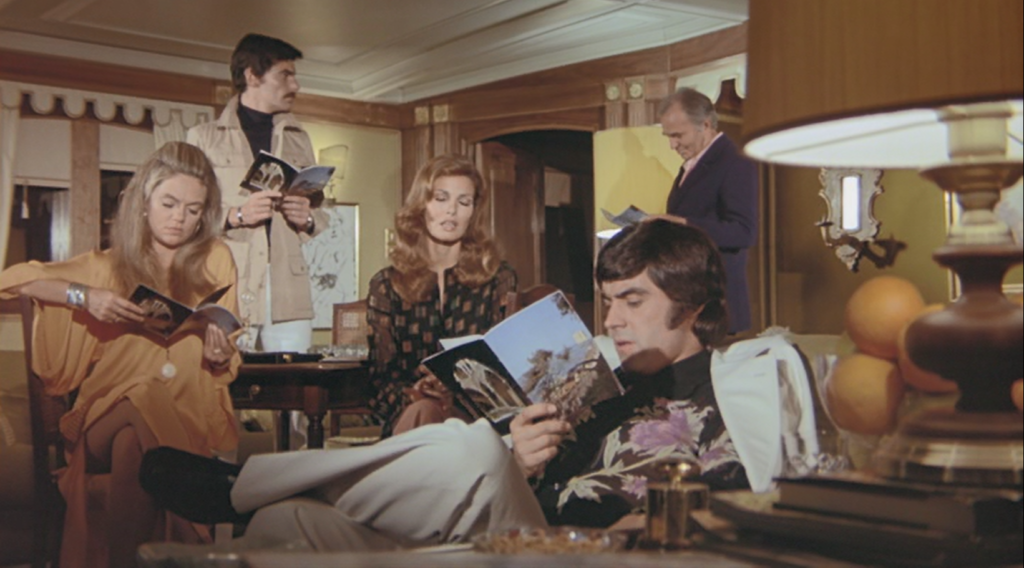

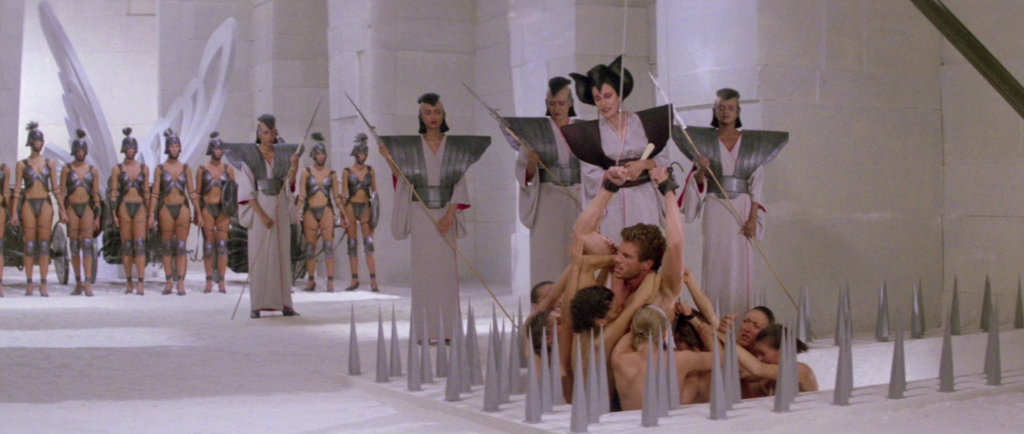

No sooner has Gwendoline discovered the rare butterfly than the three of them are captured and taken into the white walls of a lost underground city. To put it mildly, the film takes a turn. The males of this race have died out, and the females are either bald, topless slaves or Amazon warriors clad in scanty leather breastplates and thongs. A mad queen (Bernadette Lafont) rules over this bizarre Atlantis designed for the film by comic book illustrators François Schuiten and Claude Renard. The city is a surreal art-fetish-mag paradise, including impractical but visually stunning torture chambers, chariot races with women pulling the chariots, and machines that have female bodies for pistons. Everywhere, women are posed along the walls and in alcoves and along staircases as though an 80’s music video will break out at any moment, requiring much voguing. Willard tries to ineptly disguise himself as a female guard, but is exposed – literally and full frontal – and the three are taken captive. More rescues, captures, and bondage scenarios ensue, each more extreme than the last, culminating in an incoherent gladiatorial match with giant black shields shaped like bat-wings, the victor – a disguised Gwendoline – winning the spoils of mating with the only captive male, Willard, while the Queen watches. Were there lots of walk-outs when this played theaters? If so, when did one choose to walk out? Probably not at the early signs of awkward dubbing – more common, even in the 80’s, than nowadays – or the equally awkward action scenes. Perhaps when an escape from a Chinese prison is accompanied by a man’s ears getting sliced off by the apparently very sharp bars of a prison cell, or the moment when it starts to rain in the jungle, prompting Willard to demand that everyone take their clothes off (to sling them like hammocks and capture the water for drinking, of course). Anyway, the entry into Yik Yak should have cleared out anyone else on the fence about this movie. This was not going to be just another Raiders knock-off.

Willard is consumed by a pit of sex-starved female slaves while the Queen (Bernadette Lafont) watches.

And yet the film looks spectacular. The X-rated comic book designs of Yik Yak, with costumes nonsensically invoking both ancient Rome and a Kurosawa samurai film, are eye candy of the highest order. By the time the human chariot race breaks out, it’s impossible not to admire the film’s achievement, though it would be hard to justify just why this was achieved. This would make an interesting double feature with Flash Gordon (1980), which also rode the renewed interest in 30’s pulp adventure post-Star Wars, its tongue in cheek, its costume design suggesting some BDSM/fetish leanings (though strictly at a family friendly level). There are certainly some cheap effects, like a lowering stone column that threatens to crush our heroes with Styrofoam; and the film suffers from inexcusably choppy editing, weak acting (though Zabou is fun), and the expected casual racism. But Jaeckin has a photographer’s eye, and both the studio sets, including well-dressed, bustling Chinese streets, and some spectacular location footage in Morocco and the Philippines grant this exploitation picture the sheen of a big budget spectacular. All these decorative distractions make it possible, in brief moments, for the casual moviegoer to shake the encroaching feeling that the director is trying to recreate on a large scale some very private and singular desires; this may not be what you expected when you were in the lobby buttering your popcorn, but this is what you’re getting, and at least you’ll never see the like on the big screen again. “Adventure without shame,” indeed.