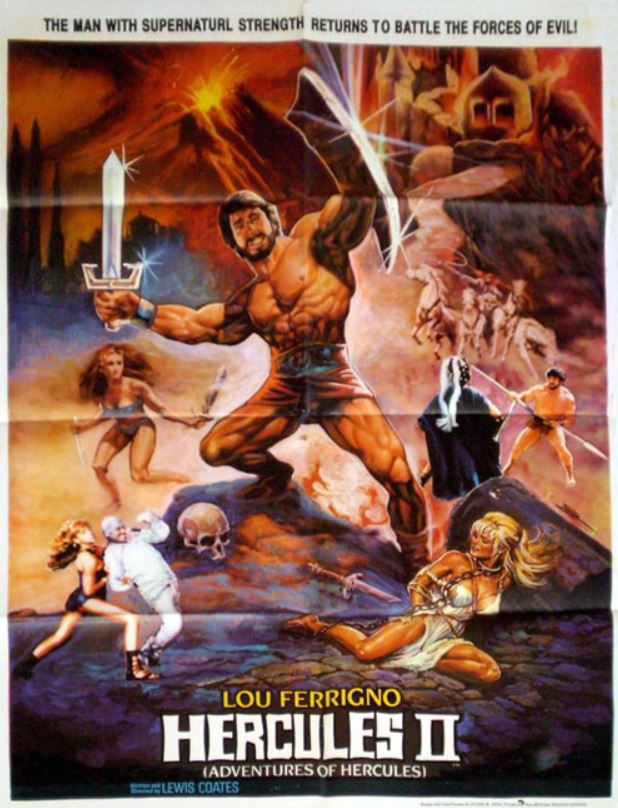

I am proud(ish) to say that I saw the Lou Ferrigno Hercules (1983) during its original run at the drive-in. My dad took me, and to this day I wonder what he thought of that decision while the film was unspooling. (He has no memory of it now – and probably didn’t a week after seeing it.) Released to cash in on the success of Clash of the Titans (1981) and to share the fortune of an early 80’s marketplace glutted with fantasy films, the film was also a revival of 60’s Italian peplum, with Incredible Hulk Lou Ferrigno as a next-generation Steve Reeves. Actually, that may have been why my dad took me in the first place. He grew up on the Steve Reeves movies, and I was a budding Ray Harryhausen (and Clash of the Titans) fan who wanted to see any fantasy movie I could. I was young and undiscriminating, but Hercules was the first film that disappointed me. Perhaps “disappointed” is inadequate. The film confused me. I was too young to comprehend that what I was witnessing was a bad film, and not just that – one of the worst wide-release films of the early 80’s. Taken on that level, and watching it as an adult, the film is a hoot. But Hercules gains some unexpected class when compared to its lower-rent sequel, The Adventures of Hercules (aka The Adventures of Hercules II or just Hercules II, 1985).

A battle with a magic knight.

The sequel shares the same director, Luigi Cozzi (under the pseudonym Lewis Coates), and you can tell. It feels like the third film in a trilogy, the first being not a Hercules film but Cozzi’s notorious Star Wars cash-in Starcrash (1979). All three share plentiful but chintzy special effects and blend the sword & sorcery and science fiction genres with no rhyme or reason. Hercules may as well take place on another planet in the far future, with its stop-motion robots replacing the traditional creatures of Greek mythology and a Mount Olympus that appears to be a misty alien planet. The Adventures of Hercules continues this aesthetic, but everything now seems rushed. The opening credits feature clips from the first Hercules film, less to bring audiences up to speed than to showcase some FX work that is actually better than what you’ll see in the film that follows. The gods are still in outer space, with glowing, colored auras like the Greek muses of Xanadu (1980) – a film that was made only five years ago but, by 1985, might as well have been ancient history. (Admittedly, being a roller-disco movie, that film was already feeling dated by 1980.) You know you’re in trouble when the very first monster Ferrigno faces is a man in a Bigfoot suit. You immediately miss the first film’s animated Erector sets.

A battle with a simian creature.

The first film retold some greatest hits of Hercules’s origin story and his 12 labors but added a villainous King Minos (William Berger), who uses the diabolical power of science. Now Minos has returned, teaming up with some rebel gods who have stolen and scattered Zeus’s seven thunderbolts. Hercules must find the thunderbolts to save the world from destruction, and with his quest he’s assisted by two beautiful sisters, Urania (Milly Carlucci) and Glaucia (Sonia Viviani). This is where the monsters come in. Each villain he defeats reveals one of the missing thunderbolts, setting up a video game structure that Cozzi reinforces with his neon-colored opticals. In an interview on the Shout Factory Blu-ray, Cozzi insists on this interpretation: he was well aware that he was making a cinematic 80’s arcade game. The prolonged, increasingly abstracted climax of the film takes place among the stars, with a floating Hercules and Urania battling Minos, and the film essentially becomes a live-action Joust or Galaga. At least it’s original. I can’t think of any other filmmaker who works in Cozzi’s style, and although The Adventures of Hercules looks the cheapest of his fantasy spectacles, it also seems the most his. (Even his bootleg Suspiria sequel, 1989’s indescribable The Black Cat, has one foot in his bizarro Starcrash universe. You can suss pretty quickly that it’s a “Lewis Coates” picture.) Other landscapes, using optical matting of strange miniatures into natural environments, are either pleasingly bizarre or, in a few cases, garishly ugly, leaving me to wonder if they weren’t shot or edited on video, given their crudely low resolution on the Blu-ray.

Antaeus, aka the Id monster from Forbidden Planet.

Cozzi is shameless in his “homages” to other classic fantasy films. Hercules borrowed moments wholesale from Clash of the Titans (a skeletal Charon on the River Styx; a semi-nude ritual bath), but Adventures takes this even further. Most strikingly, a battle with a Medusa-like gorgon is a shot-for-shot recreation of the climax of the famous Harryhausen Medusa sequence in Titans. He presents a new, anemic-looking stop-motion creature (Jean Manuel Costa is credited for stop-motion in this film), but skirts lawsuit territory by giving the monster a scorpion’s tail rather than a snake’s. Nonetheless, Hercules defeats it the Harry Hamlin way, using his shield as a mirror. (Worth noting: my 5-year-old, who has seen Titans, was very excited by the appearance of this “Medusa,” and if I saw this when I was 5, I probably would have been excited too.) In other scenes, Cozzi actually uses footage taken straight from the movies he likes. Women are chained up and sacrificed, Dragonslayer-style, to the mythical monster Antaeus, which is clearly the Disney-animated Id monster from Forbidden Planet (1956). Urania and Glaucia consult the “little people” a couple of times in the film, who are psychedelic Rorschach inkblots disguising lifted footage of the twins of Mothra (1964). In the final battle between Hercules and Minos, the two transform into scenes from King Kong (1933), rendered in rotoscope animation but easily recognizable. Perhaps the best way to consider The Adventures of Hercules is a tour through Cozzi’s own Id (monster). It’s a curious object floating through the debris of 80’s fantasy B-movies, the kind that scraped their way straight to video store shelves or late-night slots on basic cable.