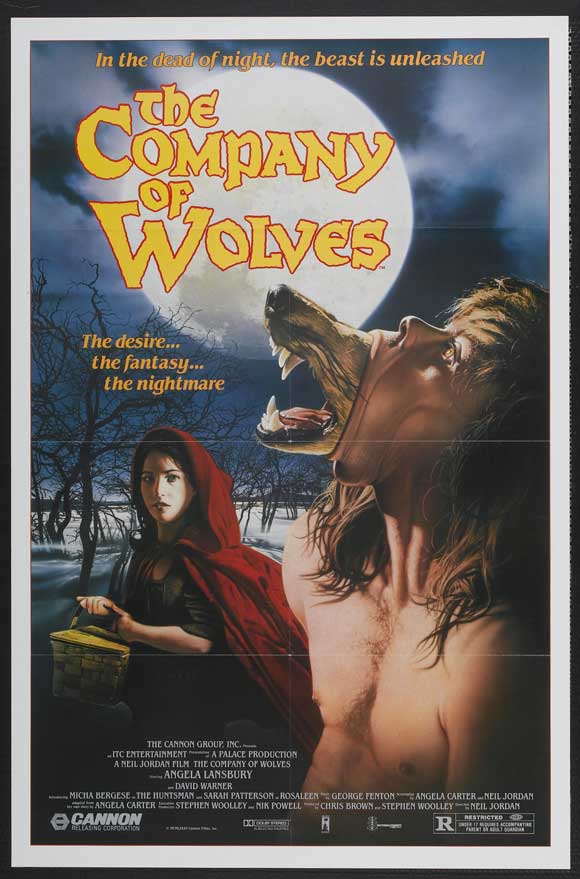

If you have seen Neil Jordan’s The Company of Wolves (1984), your first viewing was probably a lot like mine: I went in expecting a werewolf movie and instead encountered something surprisingly more. The VHS cover art, ubiquitous in the Horror section of video stores in the 80’s and 90’s, spotlighted the film’s most startling lycanthrope transformation, a wolf’s long snout bursting through a human’s jaws as it sheds its mask. The visual was announced like a trump card played against 1981’s dueling werewolf-makeup movies, The Howling and An American Werewolf in London. The striking sight makes literal the film’s oft-repeated claim that certain men are hairy on the inside. But as successful as that climactic moment is – a technical achievement worthy of a Fangoria cover, at least – Jordan’s head isn’t really in that game. The Company of Wolves is less inspired by Universal Wolf Man movies (though there’s a touch, with a perpetual fog snaking through the artificial forest) than tales more primitive, foundational, Jungian. In fact it derives from a cycle of short stories (“The Werewolf,” “The Company of Wolves”) by Angela Carter published in her 1979 collection The Bloody Chamber. Carter, who passed away in 1992, was one of the most fiercely intelligent and breathtakingly lyrical modern re-interpreters of the fairy tale, picking up and turning over tales like “Bluebeard” and “Puss-in-Boots” while penetrating straight to their core, exposing the ideas that the stories stir within us but which the original tales only danced around. She lets those tales be what they are, or anyway what they always seemed to want to be. Her versions are sexual, violent, dream-like, funny, gut-wrenching, romantic. In the film, she shares the screenplay credit with Jordan, which is more than a minor detail. Her voice almost fully informs the picture.

Granny (Angela Lansbury) warns Rosaleen (Sarah Patterson) of dangers in the woods.

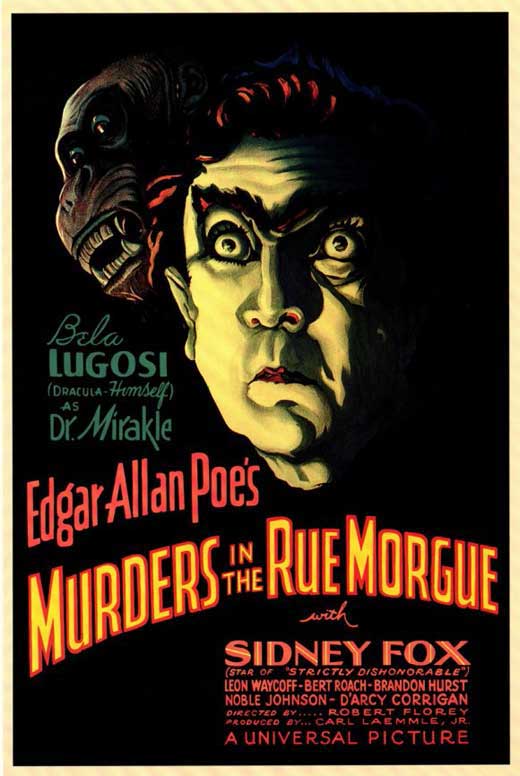

I say almost fully – to modern eyes, this is also very much a fantasy/horror picture made in 1984. For one thing, the moments of horror aim to compete in the mid-80’s marketplace. But its studio-bound environments are stunning to behold, evoking something between children’s book illustrations by Arthur Rackham and modern spectacles like Dragonslayer (1981). The village hidden in the hills and forest is an appropriately claustrophobic collage with hovels, an emerald mine, a church, farms, and a cemetery. Jordan fills every corner of the screen with odd details, partly to remind the audience that this is, in fact, a dream. This is stated at the outset when a pubescent girl (Sarah Patterson, who’s wonderful) escapes the screams of her older sister by locking herself in her bedroom with her sister’s stolen lipstick smeared across her lips, surrounded by dolls and books, falling asleep on the bed to dream – first, as a priority, of her sister getting shoved around by her dolls grown life-size, before being pursued and devoured by wolves. This brings a smile to the sleeping girl’s face. Then she becomes Rosaleen, a Red Riding Hood in origin story form, living in a single-room cottage with her parents (David Warner and Tusse Silberg) and learning about the dangers of wolves from her red-cloak-stitching Granny (Angela Lansbury, acting for the jugular). This, in itself, is an excuse for further embedded stories, making The Company of Wolves an anthology of sorts. Jordan favorite Stephen Rea (The Crying Game) appears as a newlywed who vanishes into the woods, presumed killed by wolves. Years later he returns, jealous that his wife has taken a new husband, and sheds his skin to reveal that he’s the kind of man who’s hairy on the inside. Beware the man whose eyebrows meet. After I saw this movie in the 90’s that line popped into my head unbidden whenever I encountered such a fellow, and I feel kind of guilty about it.

Rosaleen makes a surreal discovery in a nest.

Such tales from Granny demonstrate that men show their true selves with their wives after “the bloom’s off,” while Rosaleen’s mother pushes forward a counter-narrative that women can give as good as they can get. This becomes important when Granny has to face her own wolf, and Rosaleen must pick up the pieces and make a choice without any familial guidance. But Carter and Jordan take their time getting to the What big eyes you have. In the meantime, we learn how men who go into the woods alone will make deals with the Devil (who are chauffeured in fancy cars) – a potion may put hair on your chest, but at a price. Rosaleen begins to invent her own tales, and delivers one of the film’s major showcases, a wedding reception in which the pregnant ex-lover turns the groom and his party into wolves for revenge, a deliciously grotesque fantasy scene delivered with Dark Crystal-style sardonic humor. And Rosaleen contends with her first suitor, a rather piggish adolescent who plies her for a walk in the woods, which leads to getting separated, lost (first wonderfully, then strangely, then dreadfully), and pursued by a bloody-muzzled wolf that’s been feasting on livestock. The next time she walks through the woods, she goes by herself – and takes a knife with her. Where the familiar Riding Hood tale ultimately leads us is surprising, blood-racing, and unexpectedly moving. But throughout, the film never loses its essential strangeness – which only spotlights the eerie qualities of the legends themselves.

Rosaleen meets a man whose eyebrows meet.

Over the decades, The Company of Wolves, while never quite falling into obscurity (many know it), has nonetheless seemed to slip through the cracks. Though well reviewed upon release, and nominated for four BAFTAs in costume and technical categories, it often seemed to be received as too artsy for aficionados of 80’s horror, and too much the gory horror movie for those accustomed to dismissing genre films. For many critics, there’s nothing worse than a genre movie that’s putting on airs. But this has aged very well and feels neglected. This was only Jordan’s second film (after 1982’s Angel, starring Rea), but it did become a calling card that led to bigger pictures, perhaps peaking with The Crying Game (1992) and Interview with the Vampire (1994), though he’s been consistently busy ever since, most recently working on the TV series The Borgias and Riviera, and the thriller Greta (2018) with Isabelle Huppert and Chloe Grace Moretz. And yet The Company of Wolves has resisted gentrification; it’s still partly hidden away in the woods, where old rites are performed and superstitions followed, where Grannies warn little girls about the dangers of men and wolves. No sequels and remakes have been made, and those who discover it and love it maintain a quiet little cult. And – quietly – it’s one of the best fantasy films of the 80’s.