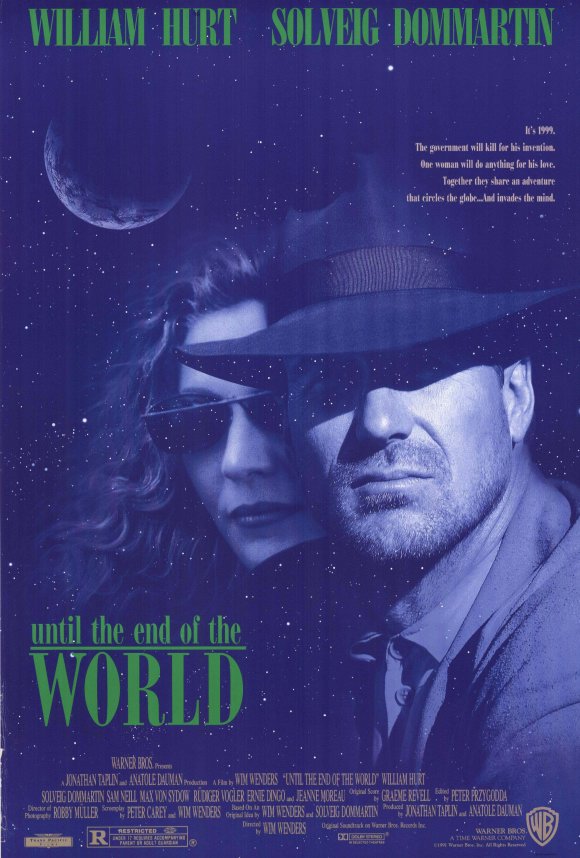

Not that the details would be particularly interesting to you (or me, for that matter), but for milestone reasons I wish I could remember a bit more about how I first saw Wim Wenders’ Until the End of the World (1991), even whether I was first exposed to the film, leading me to the soundtrack, or vice versa. Both events happened very close to one another and had the impact of an inexperienced adolescent falling in love with an exchange student well-versed in really cool music. This was at the same time that I was discovering art house and international cinema and broadening my musical interests, and it set me down multiple winding highways. I do remember selecting the cassette from some Sam Goody-type store, and watching the VHS tape on multiple occasions while happily lodged deep into a couch. Around this same time I had begun venturing into the wilds of film (outside of a Star Wars and Indiana Jones upbringing) through gateways like Welles, Kurosawa, Scorsese, Coppola, Bergman, and Polanski. Wenders was a complete unknown to me – if I knew about Wings of Desire or Paris, Texas, it was probably just as skimmed-over entries in Roger Ebert’s movie companions – and so it was the science fiction concept that drew me in. Probably. Unless it was the soundtrack first, bought on a whim because of the interesting title and some familiar bands, and the fact that I liked listening to soundtracks at the time. Again, I apologize because all this is probably as interesting as a stranger enthusiastically describing their dreams to you (a metaphor which is relevant, we’ll get to that).

Rüdiger Vogler as Philip Winter

Until the End of the World might seem like an unusual entry point to Film (capital “F”). Many comments I’ve read condemn it as a curiosity in Wenders’ filmography, a long, meandering shrug and the start of a career decline. The importance of the film in my life might seem even stranger given that what I was watching back then was a mutilated version; for its general release it was slashed from the director’s preferred 287 minutes to 158. If you don’t want to do the math, that’s more than two hours of material that was removed. Wenders has called this version the “Cliff’s Notes” – and even at that age, I was not one to read Cliff’s Notes. But if it was just a distorted, semi-coherent vision of Wenders’ original dream (this is a metaphor, we’ll get to this), and one that was cropped to pan-and-scan for home video by the time I discovered it, the film retained a certain exotic allure. I can think of a couple reasons why it caught my interest, soundtrack aside: the globe-hopping plot appealed to an adolescent boy stuck in Wisconsin; and the pacing – frenetic compared to the longer cut, though it didn’t seem this way at the time – created a feeling of traveling with these companions, a road movie you could participate in. The fact that it all reached a potently surreal conclusion in the Australian outback was icing on the cake. I was discovering new tastes, really. I had much more to learn and appreciate, but Until the End of the World was like a train ticket to the wide world of cinema.

Claire Tourneur (Solveig Dommartin) helps care for the temporary blindness of Sam Farber (William Hurt).

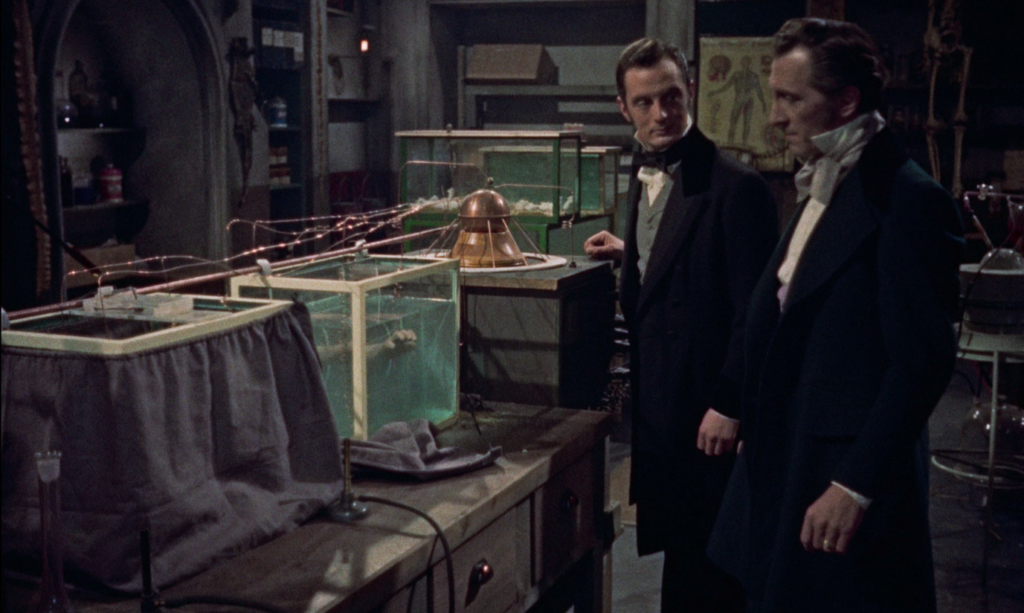

Wenders had been brooding over an epic, apocalyptic science fiction film for many years before his 80’s successes allowed him to secure financing for this big budget independent feature. His ambitious ideas – about characters wandering a near-future Earth in the wake of a nuclear catastrophe, about the death of the written word in our culture and the rising dominance of images, and about many other things – were honed through discussions with Solveig Dommartin, who played Marion in Wings of Desire, and writer Peter Carey, who would pen the screenplay. Dommartin would go on to star as the film’s restless adventurer, Claire, who (in futuristic 1999) first crosses paths with a pair of bank robbers, acquiring from them a bag of stolen cash, before she encounters another man on the run, Sam Farber (William Hurt). Sam, as we will eventually learn, is the son of a brilliant scientist (Max Von Sydow) who has invented a camera which can record images that can be transmitted to the blind. The prototype was taken from him, so Sam has stolen it back, traveling the world recording images to eventually give to his blind mother (Jeanne Moreau), all while being pursued by government agents. After he takes liberally from her bag of stolen money, Claire begins chasing Sam too, even as she begins to fall in love with him. Meanwhile, chasing Claire is Eugene (Sam Neill), who is still in love with Claire even though their relationship has always been threatened by her restless nature. Add to this mix a private detective named Philip Winter (Wenders regular Rüdiger Vogler), an agent named Burt (Ernie Dingo) who’s fond of deploying a truth serum, and – almost incidentally – an Indian nuclear satellite with a dangerously decaying orbit that’s sparking international debates, widespread panic, and even terrorism. It might be the end of days, but for a while our main characters don’t seem to really notice. Then the satellite is destroyed with a missile, and the resulting electromagnetic pulse wipes out electronic devices. By now, our cast have arrived in a desert outpost in Australia where Sam’s father continues his research, his electronics safely shielded underground. A personal tragedy leads the experiments into riskier territory – using the invention to record and play back one’s own dreams.

Recording video for the blind.

In December the Criterion Collection released Wenders’ preferred cut of Until the End of the World on Blu-ray from a 4K digital restoration. (Back in the early 90’s, when Wenders was being forced by his distributor to cut the film down to under three hours, he wisely edited and printed his director’s cut first, thinking he may have an opportunity later to release the proper version.) Previously, this longer version was screened periodically beginning in the mid-90’s, and was eventually released on a Region 2 DVD. Wenders participated in the supplements for the Criterion, and in featurettes speaks openly about his pain at having to release a wounded version of his film, one that was forced to skip across the major plot points while losing major character threads and themes. The issue here is that the plot is not the film’s raison d’être. In order to accommodate explaining where the characters came from and how they get from here to there, they hardly have time to speak to each other. The audience is distanced from them. How was this not an issue for me? Because there was enough here, spread across two and a half hours, to keep me mesmerized – as a gorgeous travelogue with goofy 39 Steps and film noir touches, culminating in a meaningful rumination on the power of images. Although they were only sketches in this edit, the ramshackle characters surely were appealing to me too; no one, not even the bank robbers, behave as you expect them to. Wenders treats his end of days scenario with a melancholy smile, embodied by characters like a detective who keeps following even when the contract is cancelled because he doesn’t have much else to do (he’s lonely); or a writer who chases Claire – even funds part of her journey – while she pursues her new lover, because he wants to see her happy (and to see what happens next, in a story he’ll write in which she’s the protagonist); or even those two docile bank robbers who become Claire’s friends for life because why? Because everyone loves Claire, perhaps. She’s one of those women. Or because when it’s the end of the world, who do we have but each other? And that’s how we all go on anyhow. The world’s ending every week, isn’t it? It takes a while.

Sam Neill as Eugene Fitzpatrick.

Certainly I was attracted to the music, which introduced me to Talking Heads, Peter Gabriel, Neneh Cherry, Julee Cruise, Elvis Costello, Lou Reed, T-Bone Burnett, Can, and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds (opening his song with a science fiction neo-noir spoken-word monologue delivered with a beer in his hand, as we can see in the short film “The Song,” included in the supplements). There’s also R.E.M., U2, Crime & the City Solution, Depeche Mode, Jane Siberry with k.d. lang (“Calling All Angels”), Patti Smith, and Daniel Lanois. After that soundtrack, I joined one of those Columbia House mail order groups and ordered anything by anyone associated to the above. Peter Gabriel’s first draft of his song “Blood of Eden,” which was not on the soundtrack cassette or CD, was a holy grail for me for years; it’s deployed so beautifully in the film, and sent me through all his albums trying to find it. That was not in vain – I was exposed to all of his remarkable albums – and it was only after my hunt was exhausted when he released Us, with “Blood of Eden” in the track listing. And he’d remade the song! That meant I had to watch the movie to hear the version that moved me so much on first listen. (He has since released his “Until the End of the World” mix.) Little did I know that there was another song that had to be cut entirely, by Robbie Robertson, which is restored in the longer cut. Would I have discovered The Band earlier if it had been included on the soundtrack? That’s really how much I was relying on this cassette to tell me what else I should listen to. And Talking Heads led me to their full discography including David Byrne solo albums. And Lou Reed led me to the Velvet Underground. It gave and gave, this playlist of Wenders’.

Dream imagery.

On the Blu-ray the film is helpfully divided into “Part 1” and “Part 2.” This isn’t an arbitrary split for disc space concerns. Wenders composed his film for two halves – the first, globe-trotting and carefree; the second, somber and inward-looking while deadlocked in the outback. Split it over two nights or take it all in at once; either way, what is remarkable for those only familiar with the shorter cut is just how much more clearly realized the characters are. Sam Neill’s Eugene Fitzpatrick, once just a background character, now becomes the film’s narrator and moves close to the center. We now understand Claire’s role in the story, which always seemed a bit surface: we are seeing her through his eyes (or through his pen, more accurately). This is the novel he is writing about her. Eugene also interrogates her relationship with Sam more thoroughly, often voicing the concerns we might be having as viewers (as in, “Him? Really? Why?”). The jaunts of the first half are more fun when they’re not cut down to the plot essentials. The characters talk to each other, they ride around in cars and on trains and listen to music and poison and handcuff each other and make love and glance elsewhere when the TV tells them that the world’s about to end. In the second half, while Wenders’ camera overdoses on the beauty of the Australian wilderness, he dives first into Sam’s family torments (surely no coincidence that Von Sydow, Bergman’s stand-in, is now prominent), and then even deeper, into day-glo dreams painted into alluringly semi-abstracted strokes of early-90’s HD technology. Watching this film after a gap of decades, it’s hard not to gasp at how accurately this science fiction film – which doesn’t seem too bothered most of the time to include SF trappings – actually manages to predict the present day. Apart from featuring GPS in cars and a funny approximation of Google, there is the powerful and haunting sight of Claire and Sam staring into their handheld devices, ignoring the world around them, addicted to their dreams. Wenders was concerned about the rise of digital media (digital moviemaking was hardly a thing in 1991, and yet!). He worried about the death of the written word and wondered if we were becoming enslaved by the images served up all around us. It’s a curious message to deliver in, well, a movie, especially one as gorgeous as this one. Yet it’s still a simple and powerful image when Sam Neill sits before an antique typewriter in the Australian desert, daring to create in an outmoded format while unable to know who in the world is left alive or how long anyone has. In the end, Wenders does return us to a final montage with more globe-hopping, more faces beaming with optimism (and less melancholy) that the world hasn’t ended yet, so you’d might as well put down your digital dreams and stretch your legs. And what a smiling relief to know that this film which served as my unlikely entry-point to – well, everything else – is actually, in this format, not a footnote but a major, life-inspiring work in its own right.