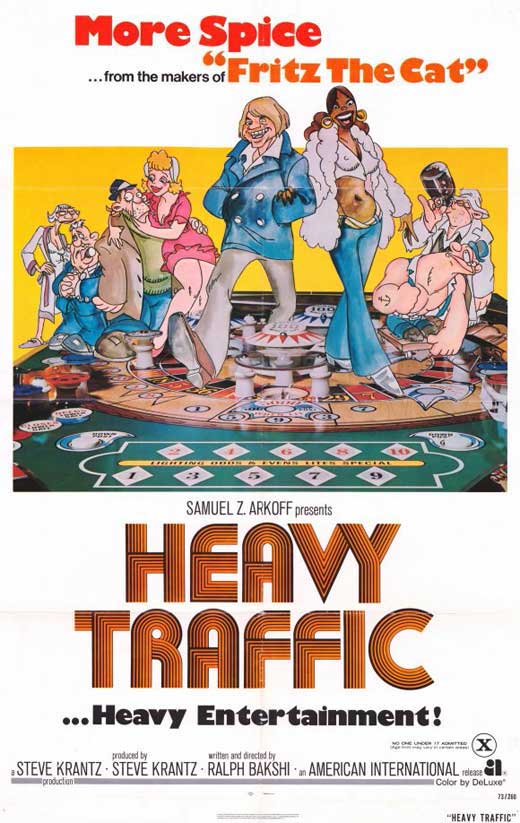

Following the breakout success of Fritz the Cat (1972), the X-rated animated adaptation of Robert Crumb’s underground comix, director Ralph Bakshi had the cachet to pursue the project he’d originally intended to be his first feature: Heavy Traffic (1973). Just as X-rated as Fritz – possibly more X-rated, judging by the content – the film is a stream-of-consciousness, semi-autobiographical portrait of an underground artist and those he encounters living the outcast, hardscrabble street life in New York City. Samuel Z. Arkoff purchased the project for American International, and was instrumental in keeping Bakshi around even as producer Steve Krantz tried to get the director fired. (Bakshi was convinced Krantz was pilfering all the profits from Fritz, and the bad blood boiled from there. These days a studio would label the fallout “creative differences.”) If the former film was a merging of two outlaw sensibilities – Bakshi adapting the work of another artist, as he would do off and on for the rest of his career – Heavy Traffic was pure Bakshi, and superior as a result. He aimed to please no one but himself. At the time, there was no other film like this, not Fritz, not anything, but Bakshi would follow it up with a series of purely American stories that act like sequels or prequels: Coonskin (1974), American Pop (1981), Hey Good Lookin’ (1982).

The domestic troubles of Angelo and Ida Corelone.

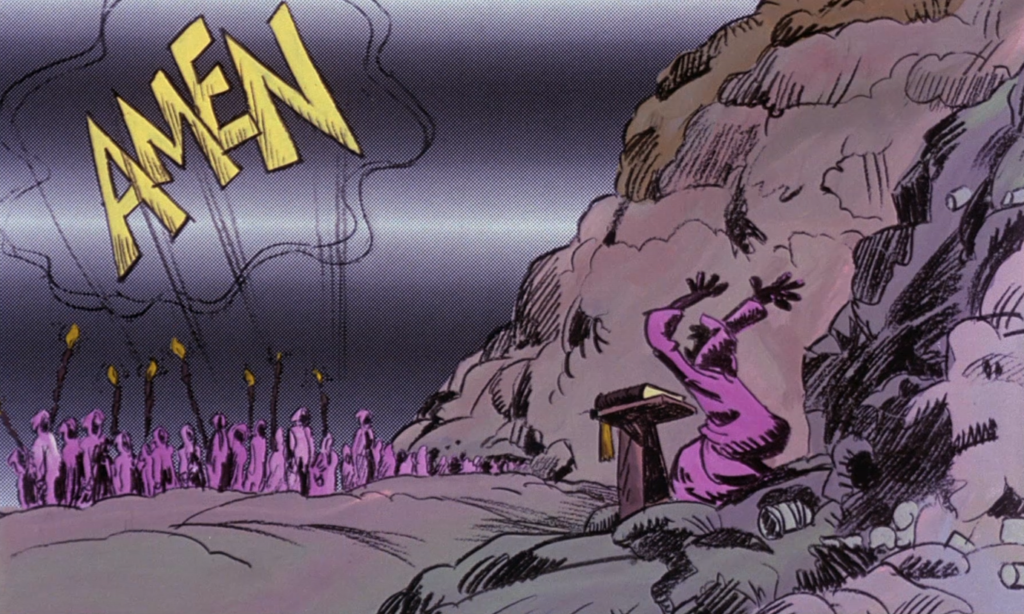

Heavy Traffic follows a young twentysomething cartoonist voiced – and played in a climactic live action sequence – by Joseph Kaufmann, who tragically died in a plane crash after completing his work in the film. His name is Michael Corleone, and the Godfather reference isn’t the only one in the film: Michael’s father Angelo (Frank DeKova) is proud to serve the whims of a grotesque and violent Mafia don. Angelo also wants his son to lose his virginity and become a real man. He cheats on his wife Ida (Terri Haven), and when he gets home, the two are constantly trying to murder one another (at one point, she shoves the unconscious Angelo into the oven and turns on the gas). Michael is smitten with a tall Black bartender named Carole (Beverly Hope Atkinson – who also gets to appear in the live action finale). Carole encourages Michael to try to sell his comic strips, which are brought to life in mini-movies animated in completely different styles: a raucous romance of rough sketches set to Chuck Berry’s “Maybellene” and a post-apocalyptic fantasy parable, using a slideshow of stills, that foreshadows Bakshi’s Wizards (1977). But Michael’s interracial romance with Carole infuriates his father, who goes to the Godfather to order a hit on him. All of these events are set thematically to a game of pinball, the characters bouncing off each other, firing and colliding and sinking, with Bakshi occasionally flashing to live action flippers and spinning silver spheres. A jazzy, haunting cover of “Scarborough Fair” performed by Sérgio Mendes and Brasil ’66 (best known for their pop song “Mas que Nada”) recurs throughout the film.

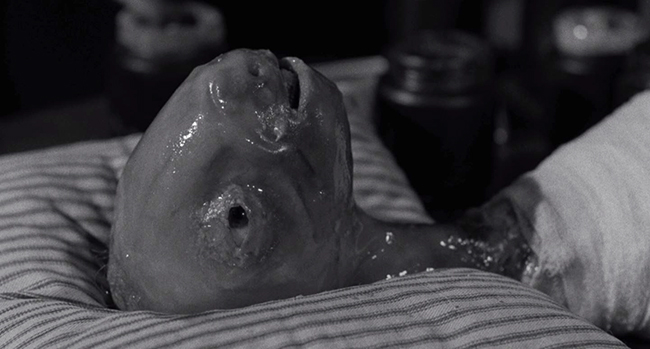

The “Mother Pile” sequence, bringing to life one of Michael’s comic strips, anticipates Bakshi’s later post-apocalyptic fantasy, Wizards.

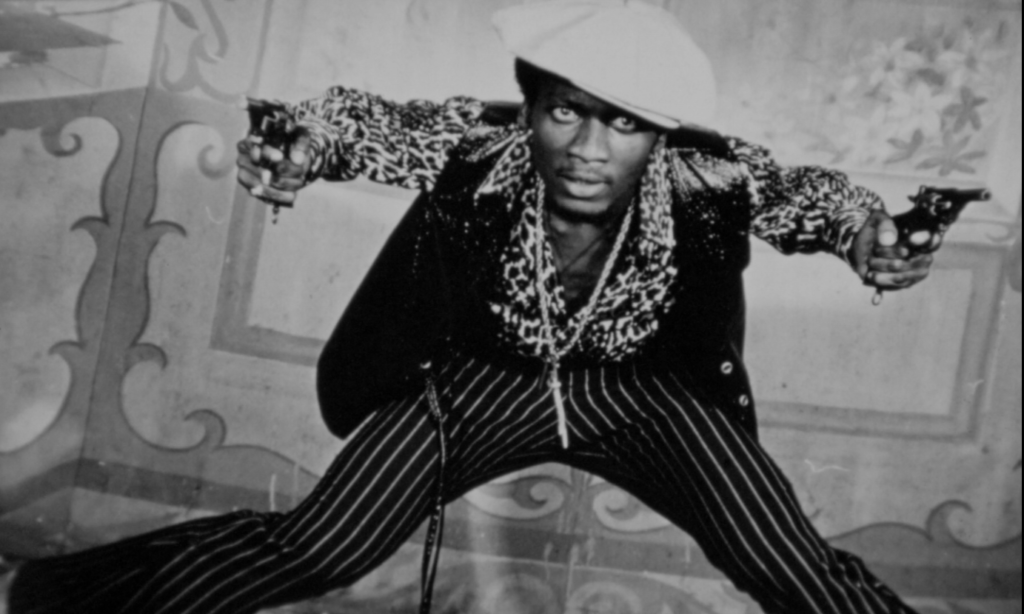

One of the strengths of Heavy Traffic is that the film frequently cedes the spotlight to minor characters, always casting a humane and curious gaze on those navigating the seedy clubs, back alleys, moldering apartments, and decrepit dives. The Bakshi trademark of naturalistic banter, played out like field recordings from the street, parts like a curtain to reveal the individual souls caught up in the urban squalor, from pink-wigged transvestite Snowflake (Jim Bates) to legless bartender Shorty. The biggest gut-punch of the film comes from one of its many digressions, when Michael, helping manage Carole’s hustle as a taxi dancer (dancing with strangers for cash), encounters his drunken, dolled-up mother trying to take the same work. As she wanders through a background of live action stock footage, her monologue of recounted memories becomes a reverie until she sees an image of herself in joyous youth – unable, at first, to recognize the person. It’s a devastating moment that is accomplished with minimal animation, the slideshow in the background coming to fill the screen as the film becomes a family album; and then we see Ida Corleone staring up at the images, dwarfed by them. Something this technically simple becomes a major highlight of Bakshi’s work as an animation director.

Slow motion annihilation.

As usual, Bakshi compiles a killer soundtrack (released on LP by jazz label Fantasy Records): in addition to Chuck Berry and Sérgio Mendes, the film features the Isley Brothers’ “Twist and Shout,” the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s “Take Five” (later to feature in American Pop), and an alternately jazzy, nostalgic, and mournful score by Ed Bogas and Ray Shanklin. Though the images can be lurid or grotesque, Bakshi and his animation staff keep it dazzling by playing with techniques throughout, integrating live action footage with day-glo highlights; rendering the Godfather and his ghoulish goons in a nightmarish blur as the spaghetti he’s devouring is revealed to contain human souls twisted among the noodles; casually incorporating surrealism and fantasy with the kind of gritty images few live action films would be willing to depict. What unites the disparate techniques is Bakshi’s ambiguous attitude toward urban life – cynical but also enormously empathetic. Heavy Traffic is a film about survivors. It’s the most bold film that American International would ever release, and it earned Bakshi the best reviews of his career.