2021 is the 10th anniversary of Midnight Only. To mark the occasion, this imaginary, rat-infested, leaky-roofed theater is raising the curtain on historically important midnight movies.

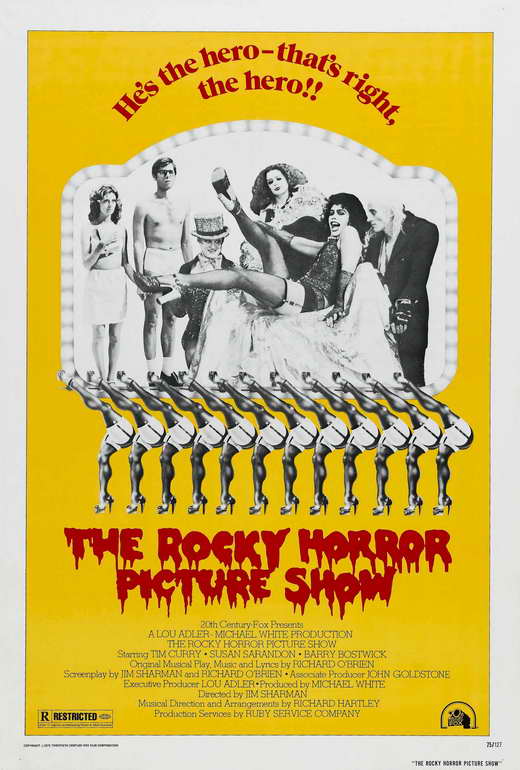

By now, The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), like Monty Python and the Holy Grail released the same year, has been somewhat tarnished by overfamiliarity. At what point does a cult movie become so embedded in pop culture that “cult” no longer applies? Rocky Horror‘s more recent reincarnations, including its notorious appropriation for a 2010 episode of Glee, a TV movie remake/tribute (2016’s The Rocky Horror Picture Show: Let’s Do the Time Warp Again), and a poorly staged political fundraiser livestream on Halloween 2020, have only contributed to the overall sanitization of what was once treated as forbidden fruit. One of the fascinating things about Rocky Horror is that you can actually pinpoint the moment when it was torn from the fingers of the midnight screening devotees and spread to the general public – when it was belatedly released on home video. Going by Wikipedia, the film was available for home viewing as early as 1987 in the UK; being an American, I can only attest that the initial 1990 US release on VHS was greeted with controversy, even a certain sense of betrayal by many. How could 20th Century Fox do that to the film? Rocky Horror was supposed to be a ritual enacted at midnight, where “virgins” attending their first screening would be initiated into a wild theatrical experience with character cosplay and audience participation including pre-scripted talkback, props like newspapers and wedding rice, and fans acting as amateur theatrical troupes performing scenes before the screen. How could one commit the sacrilege of watching the movie without all that and at any time of day? Someone could watch Rocky Horror at 8 in the morning! A frequent comment was that the movie wouldn’t survive it, that stripped of its atmosphere of a wee-hours Happening, it would be exposed as nothing more than a mediocre movie that was embraced and inflated into something much bigger than it ever was. Which was nonsense, as demonstrated by its subsequent popularity in the thirty years since, and its transformation into a cultural fixture – fawning, watered-down remakes and all.

“Dammit Janet” – Brad Majors (Barry Bostwick) and Janet Weiss (Susan Sarandon).

Following its video release, the cult of Rocky Horror might have slowly faded if the film weren’t an exceptionally strong musical at its core, supported by Richard O’Brien’s glam rock-inspired book/music/lyrics from the hit London stage show (The Rocky Horror Show) and importing some of the cast, including its phenomenally committed star, the then-unknown Tim Curry. The film was shot cheaply and quickly, produced by American record producer Lou Adler (who had purchased the US rights to the musical after being impressed by it in London) and Monty Python and the Holy Grail producers Michael White and John Goldstone, with Australian director Jim Sharman behind the camera. Sharman had previously made an outré science fiction film in 16mm black-and-white and color, Shirley Thompson Versus the Aliens (1972), before directing the London stage version of Jesus Christ Superstar and, at O’Brien’s request, The Rocky Horror Show. The film is therefore a faithful expansion of the stage production. After giving Rocky Horror a tepid and very limited theatrical release in the US in 1975, distributor Fox consciously re-strategized to embrace the film’s inherent outsider appeal and began to program it in midnight slots, picking up a devoted following at the Waverly Theater in New York City before spreading to various venues across the US and playing somewhere nonstop ever since. The film’s story was well suited for the rituals that would take shape in midnight screenings throughout the country. Our two young lovers venture with trepidation into a forbidding place, join up with a wild party, and (literally) strip away their inhibitions – as the morning breaks, they’ve been transformed into something else, even if they’re unsure of what that is and where they’ll go next.

Riff Raff (Richard O’Brien) prepares to do the “Time Warp.”

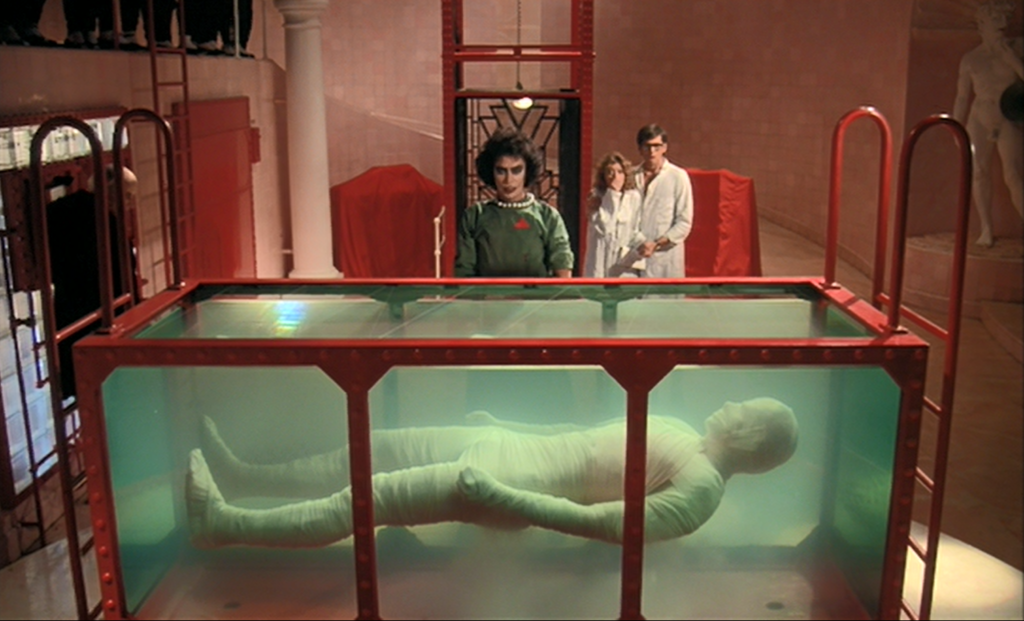

Positioning itself on the surface as a tribute to B horror and science fiction movies, Rocky Horror was partly filmed at Bray Studios, a longtime home of Hammer horror – its stately exterior given a showcase when Brad (Barry Bostwick) and Janet (Susan Sarandon) approach for “There’s a Light (Over at the Frankenstein Place).” The memorable theme song “Science Fiction/Double Feature,” performed by luscious genderless lips, makes reference to everything from The Day of the Triffids (1963) to Forbidden Planet (1956) to Doctor X (1932) and Night of the Demon (1957), among others. (When I saw a live production of the musical a few years back, the director cleverly projected trailers for the referenced movies before the show began.) The narrative structure begins in the “old dark house” mold before moving into Frankenstein territory, and while the genre conventions begin to buckle beneath the exploding ego and boundary-free passions of interplanetary transvestite Dr. Frank-N-Furter (Curry), our narrator, “A Criminologist” (Charles Gray), is there to chart precisely how our story’s path has strayed, with helpful visual aids (including, at one point, a Weird Fantasy EC comic). Sharman follows through on O’Brien’s love for genre movies with a precise restaging of the bandage-wrapped creature in a water tank from The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), though Frank-N-Furter brings his creation to life using colored dyes that form a rainbow pattern in the water, and when the bandages are stripped away, the monster is not Christopher Lee but a blond Adonis (Peter Hinwood), to Frank’s lustful delight.

Dr. Frank-N-Furter (Tim Curry) prepares to awaken his creation.

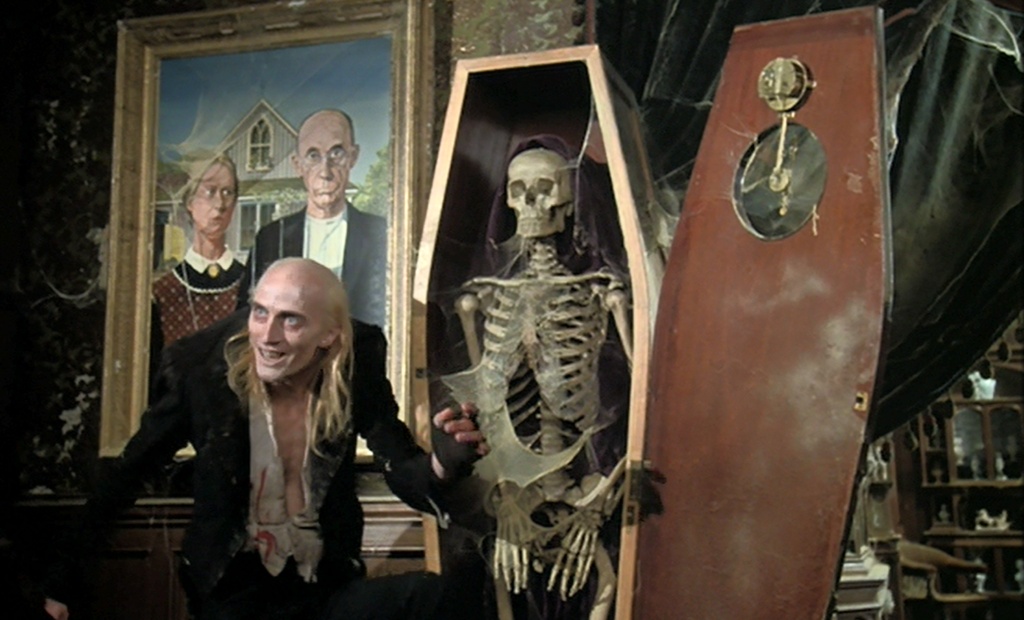

The rainbow water tank, as well as the rainbow that appears over the castle as dawn breaks at the film’s conclusion, would seem to underline the queer perspective of the film – in fact, the gay pride flag would not be created for another three years. (Even accidentally, Rocky Horror was ahead of its time.) But the film’s gender-fluid and teasingly bisexual personality feels more relevant than ever, even if “transvestite” is no longer in parlance. O’Brien and Sharman position Brad Majors and Janet Weiss as Young Republicans, listening to Nixon’s resignation speech on the car stereo like some ominous warning of what’s to come, and Brad’s cornball 50’s aphorisms echo hollowly once he’s inside Frank-N-Furter’s castle (that “hunting lodge for rich weirdos,” as Brad puts it). The Criminologist is deeply grave at what our young protagonists are about to encounter – as Riff Raff later puts it, a “lifestyle too extreme.” And so the film moves from the church-going, virginal, American Gothic world of Denton (“The Home of Happiness!”) into a cul-de-sac where motorcycle gangs gather and the sunglasses and party hat wearing Transylvanian “weirdos” (an appealingly random mix of character types) dance the Time Warp to Frank’s dictum “give yourself over to absolute pleasure.” In hilariously matching scenes, Frank seduces both Janet and Brad separately and with the same effective arguments. Ultimately, as musical theater dictates, tragedy ensues: murder, jealousy, cannibalism, the fall of Frank-N-Furter (in a coup by Riff Raff and Patricia Quinn’s Magenta), loneliness, smeared mascara and ripped fishnets, and becoming “lost in time/lost in space/and meaning.” But what’s important is that Brad and Janet, having tasted that forbidden fruit, will never return to what they were before.

Janet seduces Rocky (Peter Hinwood) to “Touch Me.”

Sharman stages his film as a sex comedy with an omnivorous sexual appetite and dashes of surreal staging reminiscent of both Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory and Ken Russell, as with an operating theater with a curved ramp to accommodate Meat Loaf’s motorcycle, or a swimming pool in which Frank-N-Furter floats in a Titanic life preserver above the Creation of Adam from the Sistine Chapel (right where they’re touching, as though Frank were the product of that spark). A giant recreation of the RKO Radio Pictures logo might have come straight from Russell’s The Boy Friend (1971), which perfectly sets up Curry singing “Whatever happened to Fay Wray?” before, ultimately, Rocky climbs the tower King Kong-like with Curry on his back. The sets are decorated with marble statues and cluttered esoterica; Columbia (“Little” Nell Campbell, who was also in Russell’s Lisztomania the same year) wears Mickey Mouse ears while in her nightgown; a stained glass window features not Christian imagery but Atlas bearing the world on his back, in a nod to Frank’s admiration of the Charles Atlas Bible. Only the famous “Time Warp” number feels a little chintzy (we need a dance hall full of Transylvanians, not the miniscule number here). But Sharman’s attention to comedic detail – Columbia’s fudging of her tap dance routine, Janet fainting on cue, Riff Raff’s and Magenta’s spider-like moves, the awkward silent pause as the Criminologist prepares to show us how to do the dance – sell the sequence. Throughout the film Sharman is focused on the actors and catching the little comedic gestures and lines perfected during stage performances. The King and Queen of course is Curry, twisting his lips into lascivious appraisals or condescending sneers, casually breaking the fourth wall, belting out his tunes as though trying to shove the camera back with his voice.

Frank-N-Furter as a “Wild and Untamed Thing” in the RKO Radio swimming pool.

It’s become fashionable now – post-Glee – to say that the film is just a rite of passage for theater kids and nothing more. This dismisses the obvious virtues that have led to that phenomenon: it’s an addictively singable musical with themes of sexual awakening, identity, and liberation that are bound to resonate with teens and college students. It’s also just fun to watch, from the performances – we should have talked a bit more about how Sarandon just kills it as Janet Weiss discovering her naughty side – to the jokes, both smart and defiantly dumb (“You’re a hot dog/But you’d better not try and hurt her/Frank Furter”). What shines is Rocky Horror‘s commitment to the message of “Don’t dream it/Be it.” Dress how you want, act as you will, be who you are on the inside even if others don’t get it. This is not a message that goes stale, which is why Rocky Horror is still revived on stage and – when this pandemic lifts – will again be playing in theaters at midnights to those who just want to lose themselves for a couple hours. It probably also plays well at 8 in the morning.